publications, Faizal Deen is the author of Guyana’s first LGBTQ+ poetry collection, Land Without Chocolate, a Memoir (1999). Born in Georgetown, Guyana, they immigrated to Canada in the late

1970s where they studied English at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario.

Earlier this month, June 7th to the 14th, I completed my week-long Twitter residency @jwilonline with the Journal of West Indian Literature (JWIL) in celebration of revered Barbadian writer, George Lamming. I first came upon my sister’s battered copy of Lamming’s acclaimed debut novel, In The Castle of My Skin (1953) during one of my visits to Jamaica in the 1980s.

The Background

When I began to virtualize the content for my Twitter residency, I did so with both readers/students and critics/teachers of George Lamming in mind. I recognized in my sister’s dog-eared copy of Castle, the one with the black and red cover and the titles in white copy, a certain kind of inheritance, an insurgent generational grounding, if you will. Whereas my mother learned, through 1940s Guyanese colonial classrooms, the literary currencies of the Brontes, my sister learned, through the postcolonial lecture halls of 1970s UWI, the literary-political value of Lamming and our own Windrush generation of writers. That George Lamming was passed on to me as a result of the access my sister had to a future-thinking post-secondary education, might seem like an individualistic observation. But the third space – the dialectical space – that opens up for me when I first read my sister’s copy of Castle, is the consequence of a collective shift in the social and political uses of education-as-a-tool of community transformation. With a sense of such inheritances in mind, I searched for similar blossoming clusters of data and information, generating portraits of preceding historical times in the evolution of what are now, for the most part, Caribbean nation-states bereft of the dashed visionary architecture of a West Indian Federation. Learning from my own family’s relationship with Lamming, which extends beyond the passing of Castle between sister and brother, I understood I would need to manipulate the fixed parameter of the tweet, which is what a sent message is called on Twitter, in order to reveal the blossoms that flower from Lamming’s proliferating significances.

What’s In A Tweet?

Coinciding with Lamming’s 94th birthday celebrations on June 8, GEORGE LAMMING BIRTHDAY WEEK, as it came to be dubbed online, features a series of (sometimes spontaneous, sometimes preplanned) daily and nightly tweets drawn from both the public and private archives of George Lamming. I speak about my residency in the present tense because it will always be available @jwilonline if one is patient enough to scroll backwards in time as my Lamming tweets become more and more buried in the virtual palimpsest of the thousands of tweets tweeted by JWIL since the conclusion of my residency. Along with George’s and Esther Phillips’s approval (Phillips is Barbados’ poet laureate and George’s partner and her poem for him form the final tweets of the residency), I was given complete control over the content of my tweets by JWIL’s Editorial Com-mittee. This meant I was free to cast George Lamming into the ‘metadata’ of digital space, a proliferating act in itself commensurate with the anticolonial imaginations of Caribbean cultural plurality for which Lamming is well known. The tweets themselves would flower into open fields of data upon data (metadata), revealing endless branches of information illuminating the entanglements of the Lamming archives. All of this would be achieved through digital practices with confusing names, such as “hashtag,” “hypertext,” and even “metadata,” but which lend themselves to digital interventions of radical decoloniality because they exceed or defy the boundaries of written and even oral communication.

I also understood that my anticipated tweets would resonate – because they were born in and of antiracist literary scholarship – with a generation of students and scholars who engage social media platforms like Twitter with generative critique and fertile banter on Caribbean literary, cultural, social, political and historical subjects. I wanted the digital politicization of my residency to explore facets of Lamming’s eclectic transnational career. But I also wanted to find ways to decolonize the Twitter platform through flashes and blurbs culled from Lamming’s storied political and cultural contributions – through text, collage, sound, fragment, image. What I wanted was to stretch the formal and structural parameters of tweets. I wanted to flood virtual space with George Lamming the way we have occupied Pandemic virtuality to flood digital space with ourselves, our Caribbean selves, our festivals, celebrations, memorials, anniversaries. Through my curated and improvised tweets, I wanted George Lamming to embark on another discursive journey, outside of and even beyond genre, through the Twitterverse, emblematizing his own arrival into the 21st century, and those “digital yards” of the Internet described by Kelly Baker Josephs in her scholarly work. But what I wanted to herald above all other transmutations of George Lamming, from analog legend to digital immortal, is his ‘virtual’ transformation through my JWIL Twitter residency into a hashtag: into #GeorgeLamming.

#GeorgeLamming

George Lamming’s digital morphing into #GeorgeLamming introduces to followers @jwilonline, the possibility of the ‘hypertextual’ nature of hashtags (#s) to produce the ‘excessive significations’ of a particular virtuality (the metadata) – a kind of Twitter foundry where tweets are moulded from the delimitation of 280 characters. Yet even within such an exact and strict character count, tweets are nevertheless able to exceed themselves and through hashtags and other hyperlinks open out into flowers of data. By “excessive significations” I mean the open-endedness of the hashtag (#) itself as it is used to tag specific or general content related to elements of Lamming’s expansive career. The hashtag (#) functions as hypertext, which means my tweets contain links to corresponding information, graphics, sound or video, with inexhaustible correlations and associations. How then would I transmute 280 characters into fractals of knowledge drawn from the expansive pre-digital historical contexts through which Lamming establishes his legacies, as writer, teacher, essayist, comrade, colleague, activist, orator, friend, confidante? Indeed how would #GeorgeLamming hold, define, record, reference, reveal, elaborate, and recover the multiple meanings Lamming signifies within the historical intersections of his thinking?

Virtualizing George Lamming means creating content that allows me to offer examples of defining relationships and connections, both personal and professional, underlined by guest columnist Anthony Bogues in last week’s installment of In The Diaspora. Bogues attests to Lamming’s intrinsic role in the 1950s and 1960s, along with fellow foundational radical figures such as Sylvia Wynter, Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, CLR James, Kamau Brathwaite, and Wilfredo Lam, in signalling the arrival on a global level of “radical anticolonial and decolonization thinking and practice.” Because of my scholarly and creative interests in Caribbean literary history, Lamming’s literary-political meanings took priority in my tweets. Through the constitutive power of hashtags (#s) to link #GeorgeLamming, both expansively and specifically, to multiple milieux, followers of my Twitter residency @jwilonline are able to consider Lamming within a contextual rigour that generates further thinking on Lamming, his collaborators and contemporaries. Consider here, for example, the historical connections forged through the following ‘hypertext’ links: #GeorgeLamming, #AiméCésaire, #PresenceAfricaine. More than a nominal linear list one finds in reference texts, followers are able to track through these specific hashtags (#s) the tree-like nature of cross-referencing Lamming with Césaire and Alioune Diop’s legendary Pan-African magazine, Présence Africaine, and in particular, the 1956 issue on the 1st International Conference of Negro Writers and Artists. The collected published papers from this historic conference include Senghor, Fanon, Césaire, and importantly, Lamming’s often-quoted address, “The Negro Writer and His World”. Other hyperlinks that widen Lamming’s role as witness and advocate of revolutionary change in the Caribbean include Lamming’s celebrated contributions as writer and editor in New World Journal (1963-1972, perhaps most notably the 1966 Guyana Independence Issue), establishing his relationships with a pantheon of esteemed figures, including sociologists, political scientists, lawyers, and trade unionists, such as David Abdulah, Cheddi Jagan, Orlando Patterson, and my late uncle, Miles Fitzpatrick.

Tracking Lamming’s literary-political connections also produced hyperlinked tweets that addressed Lamming’s contributions to revolutionary commitment and in particular, his friendship with Walter Rodney. Before his murder in 1980, Rodney asked Lamming to write “a substantive introduction” to his recently completed A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905. This stand-alone text, published posthumously by Johns Hopkins UP in 1981, would be Rodney’s last. In his magnificent 1982 “Foreword,” Lamming identifies his friend as someone who “believed that history was a way of ordering knowledge which could become an active part of the consciousness of an uncertified mass of ordinary people and which could be used by all as an instrument of social change.” I could have chosen any example from Lamming’s archive of his political commitment as a writer to revolutionary political change in the Caribbean. I could have discussed his branches of comradeship with Andaiye or Cheddi Jagan; with Cuba and Nicolás Guillén; with Grenada and Maurice Bishop; or, again, with an uncle of mine, Ken Radix, “Dix” to his comrades. The richness of these cross-references between Lamming and Rodney, nuanced by a thread of tweets, points to much more than the knottedness of friendships forged in the hopes and dreams of societal infrastructural and material innovation and transformation. If one were to arrive at Rodney’s archive through the portal of Lamming’s preface – so if one were to periodize Walter Rodney through George Lamming’s witness – one would recognize the tragedy of racial sectarianism as Guyana’s perpetual terror, as the violence that also claims Rodney’s life. In many ways, Lamming’s “Foreword” offers an emotive-political framework through which we might feel-through Rodney’s histories. The hypertextual tendencies of tweet structures, then, allow me the opportunity to read or regard Rodney through Lamming. Conversely, Lamming’s description of Rodney’s historiography as a reordering of knowledge, grounding ideas for the masses so that they might mobilize organized revolt through these ideas, encapsulates the anticolonial and decolonial strategies of Lamming’s six remarkable novels.

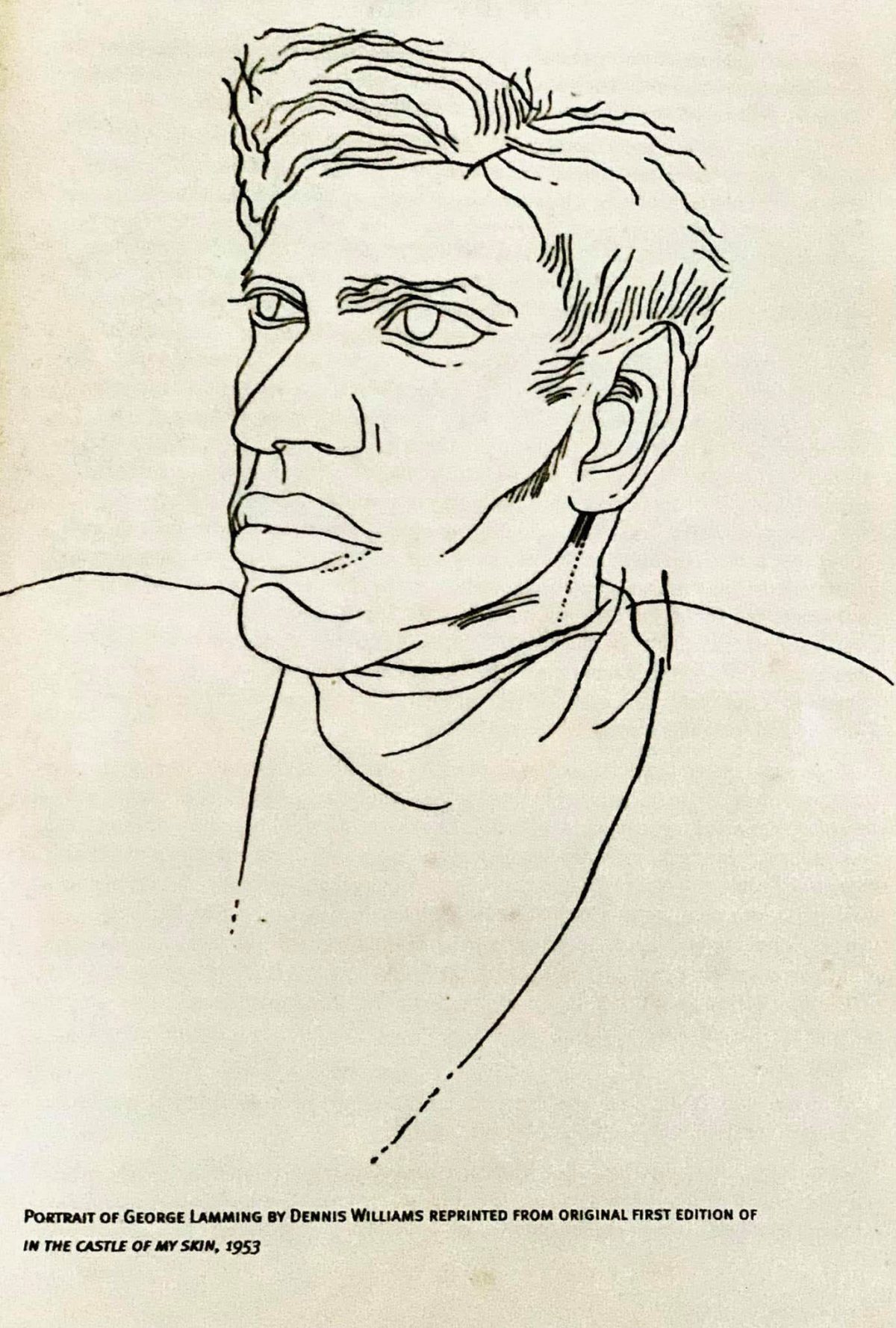

I could address the hyperlinked tweets establishing the legacies of BIM and Frank Collymore in relation to Lamming’s own education and subsequent writing career, which also opens out into hashtags that signal archives pertaining to Kamau Brathwaite, Caribbean Voices, the BBC, Henry Swanzy, along with other supplemental streams of data critical to the very historical understanding and fomenting of the idea of ‘a West Indian literature’. There are so many manifestations and meanings of George Lamming. Earle Birney’s visit with Lamming in Jamaica, where the histories of Can.Lit. and Carib.Lit. meet through the communist fraternity of poets. Carl Van Vechten’s portraits of the young Lamming, conjoining him through Van Vechten’s racial fetishism with the Harlem Renaissance. Then there is Lamming’s physical and aesthetical beauty captured by the leading Caribbean artists, painters and sculptors at the time, including Dennis Williams’ famous 1953 portrait.

Virtualizing George Lamming for my Twitter residency @jwilonline is not the first of my online quarantine projects involving Caribbean literary histories, commemoration and celebration. I am also a founding member, along with Nalini Mohabir, Ronald Cummings and Kaie Kellough, of the kamau brathwaite remix engine’s #40nightsofTheVoice @KamauRemix, which just wrapped up its 2nd Cycle with a series of lectures from founding Caribbean literary critic, Kenneth Ramchand. What I brought with me from #40nightsofTheVoice into #GeorgeLamming was a deep appreciation of the devotional energies of recorded video clips sent in to us as hypertext from friends, colleagues, readers, teachers and scholars of Kamau Brathwaite, and which together lovingly make the case that Lamming’s relevancy is undisputed as we collectively continue to reckon with the unfinished processes of decolonization.