The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not rack his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man’s smudge and shares man’s smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

– Gerard Manley Hopkins

How does one read a poem? How do you study poetry? How is it analysed? How is its meaning interpreted and the various techniques and styles of writing that make it effective and understood clarified? A description of a poem that elucidates all of those things and explains its meaning is known as, among other terms, practical criticism.

It becomes very interesting to study or explicate a poem like “God’s Grandeur” by English Victorian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins because of all the rare qualities it has. To criticise a poem is to analyse it and identify its techniques, all the different properties that make it work as a poem. Yet, lovers of poetry may say that what matters is the enjoyment of the poem, appreciating the beauty, the sound of it, and being moved by the interesting, the rare, the startling, the unusual or the profound things it has to say, without being encumbered by the anatomy, or the dissection of it.

While that might be the end product of the reading of a poem, there is as much joy in the interpretation, the understanding of what makes it work – what goes into a poem that makes it so beautiful, so interesting, so startling or so rare. It is an achievement to find out these things and to know how a poem is constructed.

That is what students are called upon to do when they are asked to comment on poems in an examination. This poem by Hopkins is one of several that are studied for the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate examination subject English B (Literature). It is just as rewarding to understand how the poem is made as it is to enjoy reading or listening to it. The mystery of it is solved. What these students get to follow are the methods of literary study.

What then, is the meaning of “God’s Grandeur” by Hopkins? And how do you find out? In some approaches to practical criticism one does not have to have knowledge of the poet and his background or the background to the poem. But it is of interest to know something, and often it helps you to understand the poem.

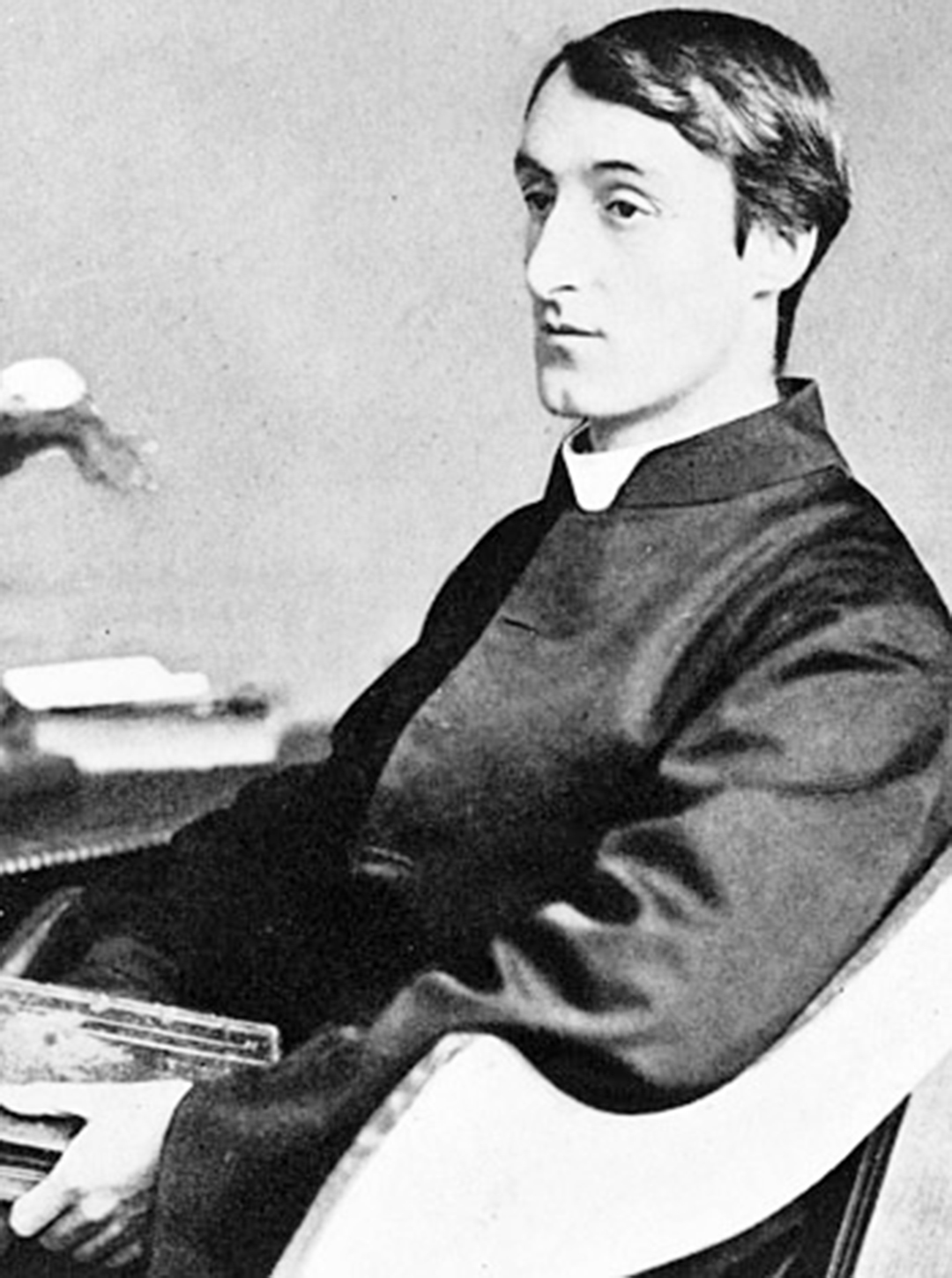

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844 – 1889) was an English poet during the Victorian period. He is very highly rated, and has been called the most original poet of the nineteenth century, and among the greats. That is because his writing was so different from others in his time, and his style stood out, departing from the conventional metre of the century. He developed what is called “sprung rhythm” which was influenced by mediaeval – Old English (Anglo Saxon) and Middle English poetry. He took a lot from those ancient rhythms and conventions and used them to diversify the metric structure commonly used in Victorian poetry. It is said that he innovated around the rhythm and brought it closer to free verse found in modern poetry.

Hopkins grew up in a family whose members were versed in the visual arts, music and poetry. His father was a poet who influenced the son and inspired the artist in him. He therefore loved to experiment and adopted much of what was found in mediaeval verse, such as the alliteration and repetitions. See the many repetitions of consonant sounds and the internal rhymes – “shining from shook foil”; “generations have trod, have trod, have trod”; “the brown brink eastward springs” and “men then now not reck his rod”.

This innovation extended to him coining words of his own and borrowing some from the mediaeval. These helped to set his poetry apart from other Victorians and make it rare, but it also made it somewhat unpopular during that time.

Another feature that arose from his family and personal background is the element of Christianity. The poem is about “God’s grandeur” – how the Lord’s creation manifests itself in different ways, including things of nature and birds, while mankind has departed from it and even destroys it. The ways and practices of men are in conflict with nature and the imprimatur of God, but his “grandeur” persists. “It will flame out like shining from shook foil” or it “gathers to a greatness like the ooze of oil”. At the end of the poem he culminates with the wonder of God’s creation in the image of a bird. The Holy Ghost “broods” over the world like a large bird “with warm breast”. It ends with an expansive expression of deep emotion, still sustaining the image of a bird – “and with ah! Bright wings”.

In Victorian times, as it was in Romantic poetry, there was a feeling that the spread of industrial development negatively affected the earth just as it had diminished mankind. A society that is caught up with commerce, manufacturing and materialism deteriorates the natural environment and devalues the finer spirit. That is why the poet uses the expression “all is seared with trade, bleared, smeared with toil”. Furthermore, man has lost any appreciation of nature or values – “the soil/ Is bare, nor can foot feel, being shod”.

Throughout the poem there is a sense of loss. The growth of industry, and the new values of material development are agents of physical, but also of human deterioration. That is why the poet values nature. But Hopkins was a Christian – he was actually ordained as a Jesuit priest, so he believes in the poem that there is a greater power watching over the world. In this poem it takes the shape of a bird. The poet believes that creation is still visible and manifests the presence of God – all around there is “God’s grandeur”.