The South Rupununi Conservation Society (SRCS) is currently conducting a population assessment of two critically endangered species of birds, having been awarded funding from Re-wild and Conservation International Guyana. The birds — the Hoary-throated Spinetail and the Rio Branco Antbird — can only be found on the borders of Guyana and Brazil and nowhere else in the world.

Since the Red Siskin was discovered in 2001, the SRCS has been working very hard to protect these birds through various projects in the conservation of birds and other animals in Guyana.

Programme Coordinator of SRCS Neal Millar said he was excited about the new project and pointed out that with this funded research they can better understand why the birds are going extinct and work towards protecting them. He said SRCS, a non-govern-mental organisation, wanted to take on the project but needed funding and approached Conservation International Guyana and Re-Wild with proposals.

Records of both species date back to the 1800s based on specimens from Brazil but little research was done on either until 2007. The Hoary-throated Spinetail (Synallaxis kollari) was discovered in Guyana along the Takutu River in 1932, while the Rio Branco Antbird (Cercomacra carbonaria) remained unreported here until 1993.

Millar explained that while the SRCS is also involved in conservation of the Red Siskin, the Giant Anteater and the Yellow-spotted River Turtle, which are considered endangered species, research of the Hairy-throated Spinetail and Rio Branco Antbird is considered more important as these birds face a higher risk of extinction in the wild which makes them critically endangered.

The birds can be found on a tiny stretch of land on both borders along the Ireng River, which is referred to as Gallery Forest. They can also be found on forested stretches along the Takutu River and the Rio Branco River in Brazil as well.

The last assessment of the birds was done in 2006 in Brazil, where rough estimates placed the Hoary-throated Spinetail population at approximately 5,000, and the Rio Branco Antbird, 15,000. It is unsure whether this figure is still accurate or if the populations have decreased.

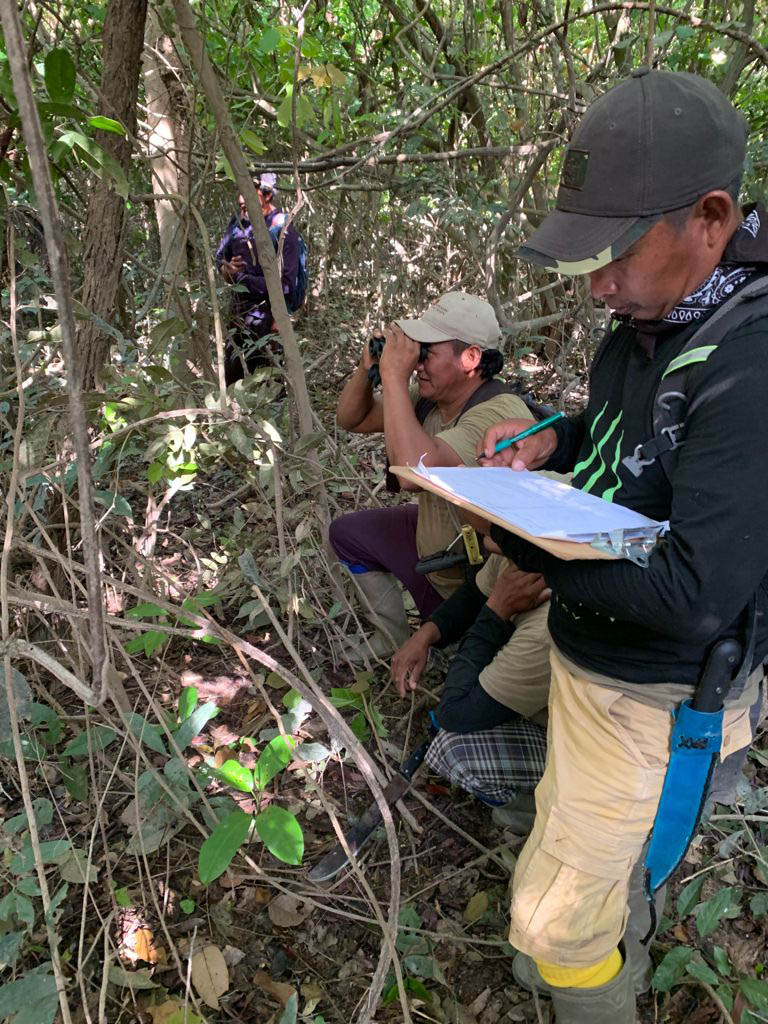

SRCS is already three weeks into the expedition which began in mid-July. The first phase of the assessment is expected to conclude by mid-August. The expedition is currently being led by Jeremy Melville assisted by scientific advisor for the US, Dr Brian O’Shea. The team consists of eight SRCS rangers: Angelbert Johnny and Frank Johnny from Sawariwau Village; Asaph Wilson, Nathaneel Wilson and Samuel Cyril from Katoonarib Village; Flavian Thomas from Rupunau Village; Dereck David from Sand Creek Village and Abraham Ignace from Shulinab Village.

The team, according to Millar, begins the day at five o’clock and spends ten hours on the rivers before returning to camp. Implementing a scientific methodology to estimate the population of both species, the rangers use what is known as the “playback method” where they play the recorded sounds of both birds and listen to hear if the birds call back to them. Sometimes the playback of the sounds would invite the birds, particularly the Hoary-throated Spinetail, to a closer location to where the rangers are and they are able to spot them using bird watching scopes and binoculars. Of the two species, the team has been able to so far record that there are more Hoary-throated Spinetais than Rio Branco Antbirds on this side of the border.

So far, it has been determined that there are two threats to the habitats of both species: fire and agriculture. While the birds face these threats on both borders, Millar shared that agriculture appears to be the bigger threat along the Brazilian border, with farmers chopping down trees to plant rice. On the Guyana side, the bigger threat seems to be fire. He added that because it is currently the wet season, they are unable to ascertain whether past fires were started because of the heat or by humans.

This is only the first stage of the project, Millar said, adding that there are plans to have the assessment done during the dry season, which would be January to March. The reason being that the dry season provides different conditions for the birds and as such their numbers may differ.

However, he shared that the funding is only expected to run for another week, and is not enough to see the project through the second phase. As such, more funds will be needed to follow through with that when the time comes. The SRCS is hoping other organizations can collaborate in this effort.

Meanwhile, Millar said, the SRCS will be educating local indigenous communities and nearby private landowners like Waikin Ranch so that together with the NGO, they can work to develop a conservation action plan to protect the birds and stabilize their population. While nothing has yet been decided, among the possibilities to be considered are: monitoring of the species, habitat restoration, and creating a community conservation area. SRCS will also be looking to work with stakeholders from Brazil as part of a collaborative effort in preventing the species from going extinct.

The conservation of the species will also help to boost the tourism sector. Prior to the pandemic, the Rupununi was one of the top places to be visited by birdwatchers.

“Until now, the main attractions of the Rupununi have been the Red Siskin, Sun Parakeet, Toco Toucans, Jabiru Storks and many others. But these two birds, as they can only be found here on the border of Guyana and Brazil, and nowhere else in the world, are a major unique attraction. They can be promoted to increase the Rupununi’s growing tourism market. This comes at a time when the Rupununi is looking to bounce back with tourism after the devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Millar said.