Mainly in the ancient county of Berbice, these distinct names of rural villages and places spread all along the flat, muddy coastline of Guyana, roll off our tropical tongues with some unease, and we mispronounce many of the Gaelic ones daily, without stopping to consider the intertwined history or geography.

Yet, our legacy of labels for former lucrative slave-powered sugarcane estates and similar holdings of coffee and cotton, is a shared story. It originates from across the other side of the Atlantic, in the mountainous and misty, loch-filled Scottish Highlands about 5, 000 miles away, in a cold country of close-knit, kilt-wearing clans that collectively chose to conveniently forget and efface their lead in British and personal empire building.

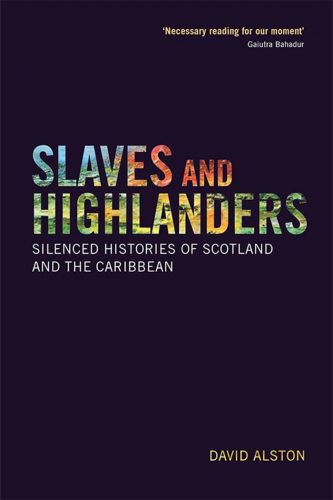

For more than 20 years, the historian Dr David Alston has been on an often lonely road, carefully researching the extensive role of Highland Scots in the transatlantic African slave trade, and the profitable plantations of the Caribbean, but especially the prized jewel British Guiana, where they came to seek, make, keep and add to their fortunes.

From his restored, 19th-century merchant home in the Scottish seaside town of Cromarty with a population of just about 800, looking out on the firth, Dr Alston posted the unvarnished truths of his findings on a public website simply called, “Slaves and Highlanders” https://www.spanglefish.com/slavesandhighlanders/index.asp?pageid=261689

He is among the first Scottish historians to draw attention to the prominent part played by his countrymen and key figures from within his small community, in the slave trade and the indentureships that followed abolition.

Due for release this month as a scholarly book of the same name, subtitled “Silenced histories of Scotland and the Caribbean,” his 400-page publication by Edinburgh University Press, is an important and courageous collection of evidence that seeks to help correct the national narrative, including the myth that the Scots were more egalitarian than the English, and that they did not engage in the slave trade.

In profound parts, as painful as it is plaintive, Dr Alston’s dedicated work offers powerful glimpses of the victims and perpetrators of widespread abuses, the bloody terror and casual horror of everyday estate life and the brutally suppressed revolts, from the initial haunting page with the severed and bleeding head of a slave taken from a reproduction for Cromarty Courthouse Museum’s ‘Slaves and Highlanders’ exhibition in 2007, based on an illustration by Joshua Bryant for his account of the August 1823 Demerara Slave Rebellion published in Georgetown, in 1824.

Above it, Dr Alston cites a historical excerpt, “[It was] a scene which none could well bear, the young men were getting bewildered with it, but one old Scotchman Donald Young was as cool as if he had been shooting a partridge . . . Orders were given [to other slaves] to cut off the heads of some of those shot; their own comrades, who had just seen them in life, were most inhumanely set to mangle the bodies of those who had been their friends, sawing off their heads with cane knives and screwing them onto sharpened long poles.”

His book details the powerful family links and clan networks among the plantation and slave merchant owners, that would hurtle many of them into high political office in the United Kingdom, even as they used the proceeds from slavery and generous compensation to build lavish mansions, several of which remain in Cromarty.

Pointing out that slave ownership was not confined to the upper classes, and that an enslaved person was considered a sound investment by ordinary Scots willing to inflict extreme punishments, the academic shows wealth from the Caribbean was used to transform the Highlands, becoming linked with trade to and from the British colonies and with the financial systems on which the plantations depended. Key chapters also look at the Highland’s ‘Black History’ or the presence in the area of enslaved Black people, of free Black servants and of the mixed race children of Scots and enslaved and ‘free coloured’ women.

“Scots were involved in every stage of the slave trade: from captaining slaving ships to auctioning captured Africans in the colonies and hunting down those who escaped from bondage. This book focuses on the Scottish Highlanders who engaged in or benefitted from these crimes against humanity in the Caribbean Islands and Guyana, some reluctantly but many with enthusiasm and without remorse. Their voices are clearly heard in the archives, while in the same sources their victims’ stories are silenced – reduced to numbers and listed as property.”

In an advance copy, he writes, “If we had ‘a keen vision and feeling’ for all the ordinary human lives destroyed or marred by slavery it would indeed shake the frames of our being. In writing this book I have tried to hear something from beyond the silence. Something not merely from the white northern Scots but from the enslaved Africans and their descendants, from those who reclaimed their freedom, from free women of colour, from the Black Caribs of St Vincent, from house servants, and from children of mixed race who found themselves in the increasingly racist society of Britain in the mid-1800s.”

He adds, “But these voices remain a whisper. And yet even that whisper is difficult for us to bear. We (The Scots) are indeed ‘well wadded with stupidity’ and are inclined too readily to wrap ourselves in comfortable narratives of Scottish and Highland victimhood,” a reference to the Highland clearances, when thousands of tenants were evicted from agricultural lands.

In 1833, Britain’s Parliament finally abolished slavery. Negotiations between the state and the main grouping defending slave owners were protracted because of the vested interests represented in the House of Commons and the House of Lords. “The negotiated settlement brought emancipation – but only with the system of apprenticeship tying the newly freed men and women into another form of unfree labour for fixed terms, and the grant of £20 million in compensation, to be paid by the British taxpayers to slave owners,” the University College London states on its invaluable website, related to the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/project/context/.

The record sum is the equivalent of about £17 billion. But that money was given to 3 000 slave owning families for ‘loss of human property’ and represented 40 percent of the British Treasury’s annual spending budget. The Treasury famously tweeted in 2018, “The amount of money borrowed for the Slavery Abolition Act was so large that it wasn’t paid off until 2015. Which means that living British citizens helped pay to end the slave trade.” It was later deleted, after causing an uproar.

The West India house of Cromarty’s clansmen Davidsons & Barkly collected £164,875, with the equivalent purchasing power today of £14.25 million for dozens of estates across the Caribbean from Antigua to Trinidad, and including British Guiana’s Plantations Highbury, Bellevue and Rose Hall. It was shared among just four partners, 32-year-old-old Henry Davidson and his younger brother William, 66-year-old Aeneas Barkly and his only son Henry.

ID reads about Henry Barkly who would become the Governor of British Guiana, and later Jamaica, prompting Lord Grey, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, to refer to his “remarkable skill and ability” in addressing the colony’s economic issues by introducing indentured servants from India and Asia.