Scott B. MacDonald August 5, 2021 Global Americans Contributor

These words were spoken by Eric Williams on his first day as prime minister of the newly independent Trinidad and Tobago. While his comments were made several decades ago, they retain relevance in today’s world. The Caribbean has long enjoyed a reputation for being one of the most democratic regions in the world. The 20-odd countries and territories that stretch from the Bahamas to Guyana and Suriname have a generally strong track record of regular elections, political stability and a lack of politically motivated violence. (The notable exceptions to such trends are Cuba, where the Castroite regime is currently being shaken by widespread protests against the government; and Haiti, where President Jovenel Moïse was brutally assassinated last month, further plunging the country’s future into uncertainty.)

Despite the Caribbean’s seeming confidence in the ballot, Caribbean countries nevertheless face considerable challenges in keeping their democracies alive. As Williams and a long stream of Caribbean leaders came to understand, elections alone do not make a democracy; there are many other factors that must be taken into consideration in order to ensure good governance. For much of the Caribbean, herein lies the challenge. Holding elections is the easy part; upholding the rule of law, civil liberties, freedom of the press, gender equality, and government transparency are challenges—and without them, there is no foundation for democratic governance. Indeed, as Williams stated in the same address, “Democracy means responsibility of government to its citizens, the protection of the citizens from the exercise of arbitrary power and the violation of human rights and individual rights.”

The issue of good governance has only grown more significant over the past decade, due to globalization, the “shrinking” of the world due to better and faster mass communication (i.e., the internet, television, and social media), and increasing scrutiny of the accountability of governments to their citizens. According to the World Bank, governance “… consists of the traditions and institutions by which authority in a country is exercised. This includes the process by which governments are selected, monitored and replaced; the capacity of government to effectively formulate and implement sound policies; and the respect of citizens and the state for the institutions that govern economic and social interactions among them.”

At a more granular level, the World Bank compiles its Worldwide Governance Indicators by analyzing factors including voice and accountability, political stability, governmental effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. The World Bank is not the only international organization that examines the issue of governance. The major ratings agencies (Moody’s Standard & Poor’s, and Fitch) also consider issues such as political stability, corruption, and various social indicators. The Berlin-based NGO Transparency International also ranks countries from the least corrupt governments to the most corrupt in its Corruption Perceptions Index.

Governance and elections were a major focus throughout the Caribbean in 2020. Indeed, the fact that Caribbean governments were able to hold elections—generally smoothly-run and plagued by minimal political violence—during the COVID-19 pandemic says something about the commitment of local populations and governments to democratic governance. As demonstrated in the table above, these elections produced changes of government in Anguilla, Belize, the Dominican Republic, Curaçao, Guyana, and Suriname.

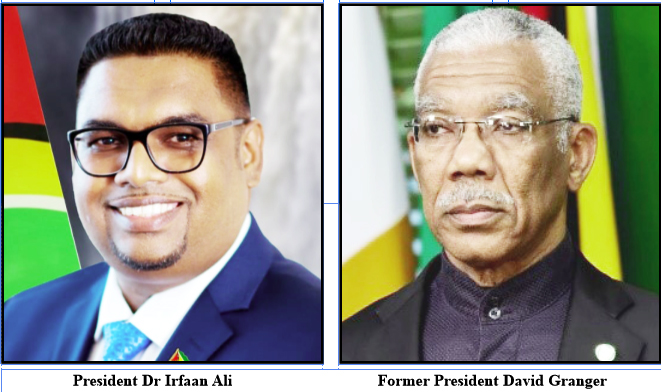

The respective 2020 elections in Guyana and Suriname strongly tested the strength of democratic governance. In Guyana—where, due to the recent discovery of major offshore oil reserves, the 2020 elections were closely watched internationally—the incumbent government of then-President David Granger sought to postpone the scheduled elections, turning to the courts to stall the vote and then to eventually challenge the results. (This process, of throwing such matters to the courts with the hope of overturning electoral results, represents a phenomenon that some have called “judicialization.”) Granger’s attempts to overturn the electoral results raised tensions between the two major parties—Granger’s People’s National Congress-Reform (PNC) and current President Irfaan Ali’s People’s Progressive Party/Civic (PPP)—which are linked, to some degree, to the two major ethnic groups in the country. (The PNC is supported primarily by the Afro-Guyanese population, while the PPP draws its support principally from the Indo-Guyanese population.) The political turmoil in Guyana also drove external forces—such as the Caribbean Court of Justice, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom—to become involved, pressuring Granger and the PNC to concede their defeat and seek a nonviolent constitutional resolution to the crisis.

The Surinamese election was similarly fraught with a number of challenges, including a slim electoral margin, the criminality connected to outgoing President Dési Bouterse, and a major economic crisis (provoked by a combination of gross policy mismanagement and widespread corruption). Despite such factors, however, the election proceeded as scheduled; and, after a period of uncertainty regarding the results, victory was declared for the opposition and accepted by the former ruling party.

The challenges facing governance and democracy in the region are hardly unique to the Caribbean. In the past year, the U.S. has witnessed a distressing, disputed presidential election, various attempts to challenge the results in the courts, and an angry mob storming the U.S. Capitol building on January 6, 2021. In the U.K., disagreements over the 2016 Brexit referendum left the country’s political system close to paralyzed, with three Prime Ministers occupying Number 10 from 2016 to 2019 and Parliament deadlocked over how to manage the country’s exit from the European Union. In other Western democracies, including Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, and Sweden, populist political parties have made considerable gains in recent years, reflecting public anger over such issues as immigration, social and economic inequality, and limited employment opportunities.

Questions related to good governance, therefore, are not likely to go away any time soon. The Caribbean is still struggling to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic and manage the associated economic carnage. While most global economies are expected to return to growth, the economies of the Caribbean will be forced to emerge from a very deep contraction. The International Monetary Fund projected that the real GDP of the Caribbean economy contracted by 8.1 percent in 2020; although projections for 2021 are expected to be somewhat rosier, there remains considerable work to be done to rebuild regional the regional economy, while the threat of COVID-19 has not entirely disappeared from the picture (as reflected by the rapid spread of the highly-contagious new Delta variant).

While the vast majority of nations in the Caribbean are characterized by a liberal democratic system, they nonetheless face major challenges. Recent events in Guyana and Suriname served as strong tests of the durability of democracy in those particular countries. Jamaica’s 2020 election, plagued by low rates of voter participation, indicated the challenges of holding elections in the middle of a pandemic, and also reflected a certain degree of popular discontent with regard to issues such as corruption and governance. Rounding out the picture, the Dominican Republic held elections under similarly difficult, pandemic-related conditions, with Luis Abinader and his Partido Revolucionario Moderno ending the 16-year reign of outgoing President Danilo Medina’s Partido de la Liberación Dominicana.

Among Caribbean governments seeking to preserve democratic systems, Haiti remains the odd nation out: its political system is badly fragmented, its institutions are weak, and public trust in the government remains almost nonexistent. The assassination of President Moïse only reflects the abysmal state of affairs in Haiti, which even the successful and peaceful holding of long-postponed elections may be insufficient to resolve. Foreign donors and international organizations are reluctant to intervene, considering the repeated failures of such efforts in recent decades. Meanwhile, Port-au-Prince and large swathes of the rest of the country are increasingly marked by gang violence, political infighting, and a generalized breakdown in law and order.

Haiti’s troubles demonstrate to its Caribbean neighbors the importance of confronting the difficult challenges associated with democracy and good governance. While democracy is not an easy thing to keep alive and well, doing so remains indubitably preferable to living in a failed state—a reality to which leaders and citizens throughout the Caribbean should give greater acknowledgment.

Scott B. MacDonald is the chief economist at Smith’s Research & Gradings, founding director of the Caribbean Policy Consortium, Senior Associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and a Research Fellow at Global Americans. He is currently working on a book on the new Cold War in the Caribbean.