Introduction

As indicated in last week’s column, today’s begins with the reproduction of the list of ten key references to guide inquiring readers who may need further information on the practice of cash transfers as a poverty policy intervention tool. Following that, I identify some of the technical challenges intrinsic to the Buxton Proposal that I have raised earlier. Further, I shall also address a few other reasonings in support of cash transfers to Guyanese households as a priority income poverty intervention policy tool.

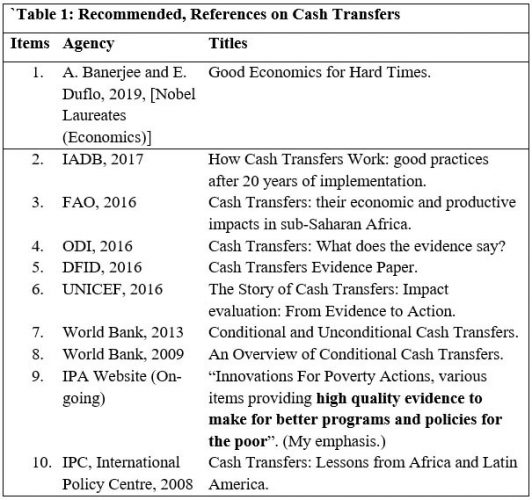

References

The references promised last week are provided in Table 1 below. The list covers studies conducted under the aegis of leading Development Agencies and Authorities. In a variety of ways all the listed studies attest to the efficacy of oil-revenues-to-citizens cash transfers as a poverty policy intervention tool.

Technical Challenges

To be frank with readers, several technical challenges remain intrinsically stubborn in the Buxton Proposal. These ultimately drive my call from the outset for a state sponsored-feasibility and pilot study. Ultimately, therefore, the Proposal is dependent on the level of political support it can garner nationwide. Despite their large numerical plurality, it cannot be overlooked that the poor, vulnerable, and powerless among us, often act in contradiction to their real objective interests. This is all too often due to their systemic denial of equal access to opportunities from which they could be positioned to benefit from Guyana’s oil wealth. The Buxton Proposal seeks to break the cycle of this negative dynamic.

There are however, other similar technical challenges. Thus, one finds that, success with oil revenues-for-cash transfers to household schemes are founded on very high-level multi-disciplinary skills. It is for this reason that I have advocated for the University of Guyana and the Bureau of Statistics to form the core of the Working Group undertaking the Feasibility and Pilot Study of this Proposal.

There are other such technical issues, which it is hoped the GoG-sponsored Feasibility and /Pilot Study would address. One example worth mentioning here, is the range of practical problems arising from a robust and workable (operational) description of a household, with minimal ambiguity. Such a definition will have to withstand “legal challenges” given the sums of money involved.

Another example is at what point does the Proposal commence? I had recommended when Guyana’s daily rate of production, DROP, reaches (one million barrels of oil equivalent, boe. The maximum of US$5,000 annually, is reached at Full ramp-up of oil production, which is fixed at a DROP between 1.5 and 2.5 million boe. A DROP of 1 million is approximately two-thirds a DROP of 1.5 million; so, the Proposal pays two-thirds of US$5,000 or US$3,333. Alternately it can operate so that given any DROP the Scheme starts from; the proportionate principle would apply.

There are also further concerns! Thus, should the payment be annual, or can it be sub-divided into smaller periodic payments. Relatedly also, when production plateaus and begins to decline should the payment “decline, pari passu”. If yes to what minimum DROP?

I would recommend that, such issues should be addressed in public consultation in order to benefit from the advice and guidance of stakeholders in the process.

To operate with fully-risked expectations, the best recommendation I can offer is the swift pursuit of the socio-economic appraisal of the Buxton Proposal. The original aim was its completion within one year of First Oil, allowing for a commencement date in 2022. This I believe would have given sufficient time for the Authorities to complete the recommended studies and prepare for start-up two years from now. This period gives households time to plan their way forward.

Reasonings

First, readers should know that the literature makes it quite clear, the reasoning in support of cash transfers to households as a poverty intervention policy relies on empirical evaluations of such schemes, rather than, as some naively believe, a new set of poverty prevention and alleviation theories. Indeed, it is this empirical foundation, which constitutes the strongest appeal of these schemes. Furthermore, I am convinced, after decades of studying this subject that cash transfers schemes have been over the past two decades, the most thoroughly researched, investigated and studied development intervention, worldwide.

This reasoning has been so common-place that, about a decade ago (2011), the Department for International Development (United Kingdom) declared: “During this millennium a quiet revolution has seen governments … invest in increasingly large-scale cash transfers programmes.” The Agency further reported “These [programmes] now reach 0.75 to 1 billion people.”

Conclusion

Next week I take this presentation further bearing in mind it’s not a new-fangled prescription but instead an operationally rooted proposal in practice worldwide.