Every few months a new Marvel film emerges and every few months critics write critiques of the individual movies that dovetail as critiques of the entire Marvel collection. How could we not? That’s the nature of the Marvel enterprise since the Marvel Cinematic Universe became the pop-cultural behemoth of its time. It’s never quite the individual films but their existence within a larger framework that confronts us. Each film gestures to the past or reaches instinctively for the future. The chain depends on its motion creating something that projects itself as the natural order of things.

How fitting it is then that “Eternals” is concerned with the notions of order. The opening crawl takes us back, all the way to “In the beginning”. Those loaded words, popularised in the Bible, are not accidental. In “Eternals”, the MCU finds God. The source is Jack Kirby’s story “When Gods Walked the Earth!” which traces how thousands of years ago the god-like Arishem sent ten humanoid Eternals to Earth to help the human-race fight the invasive Deviants. The immortal Eternals were tasked with ensuring that the Deviants were destroyed, but warned not to engage in any non-Deviant woes. Despite their powers, with which they could potentially change the course of humanity, they would not interfere unless their Arishem commanded. When the last Deviants are destroyed, they are left without a purpose, but still on the planet. For centuries, they live among humans, bearing the weight of seven thousand years of human chaos. It’s a heavy load.

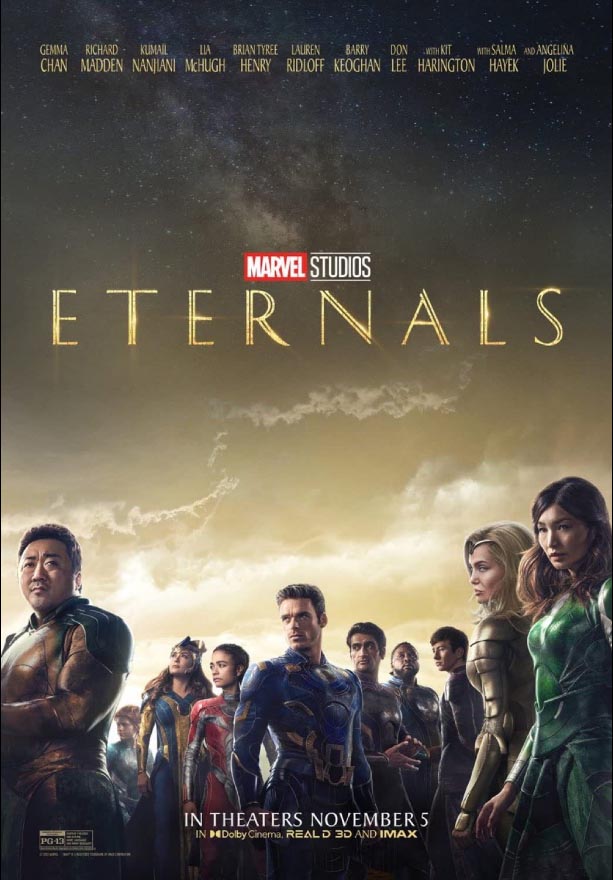

When the film picks up properly in the present-day, the group have scattered across the globe and our focus is on Sersi. As played by Gemma Chan, Sersi is an empathetic teacher in London whose Eternal power is manipulating matter. The period of waiting is interrupted by the appearance of a Deviant – not destroyed after all. And the band must regroup. Why have the Deviants returned? And why haven’t they been called back home by their creator? And it’s important to recognise that there are three central existential preoccupations that dominate the actual core of “Eternals”. Is humanity worth saving? When does one dare to question one’s creator? And what are the limits of the greater good as personal – or even communal – ideology?

The first one is presented as the initial concern. The planet is on the verge of destruction and the Eternals, living among humans for so long, feel beholden to the human race. But why is humanity worth saving? Throughout “Eternals”, Chloe Zhao (who co-writes the script as well as directs) plays around with timelines. Its prologue is in 5000BC and it closes in the present. In between that we move between the present and various periods of history, constructing the tapestry of how the Eternals came to be. As we hop through time, the film wants to explain the context of these characters and – implicitly – explain their relationship with the humanity they exist alongside. But is it enough?

Zhao (and cowriters Patrick Burleigh, Ryan Firpo, Kaz Firpo) takes it as a given that we would be convinced by virtue of our own humaneness but it’s not enough that we root for the saving of the world by mere automation. A film must show us its thesis. But, “Eternals” seems ambivalent about the very thing its heroes seem devoted to, so much so that the twist that hurtles the narrative into its final act feels lopsidedly logical in a film which has shown us none of what it gives as lip-service. But the disconnect between the motions of an idea and the actual evidence in “Eternals” leads to a schism where “Eternals” is conceptually about great and important things, but often feels like a facsimile. Ben Davis’s cinematography can understand the beauty of these landscapes and these people in a theoretical way, but it’s too weightless and remote to be really messy or to explore the discomfort of these emotions.

In a moment of great tension, we flashback to a conversation from a few days before the narrative picks up in the present. It reveals much, but that conversation is only referring to another actual conversation that occurs centuries ago where the actual twist occurs. But we do not see that conversation, it only exists as a reference. It’s par for the course for “Eternals” where something knottier, something messier, something more vivid feels just out of frame. But “Eternals” elides the actual complications. In an incongruous moment we flashback to an Eternal bemoaning the Hiroshima bombing, a brief moment of dismay at humanity but we soon cut away – the moment a brief note that feels disconnected in its casualness.

It feels telling how many of the key moments in “Eternals” (the music swells, the camera pans out for a wide-shot with a gloriously imagined landscape in the background) are moments where the Eternals are lined up in formation looking out at us from the screen rather than each other. The moments feel rich with potential as images projecting heroism, but truly empty when considered as heroic characters existing in relation to each other. What do these people mean to each other? What have been the implications of those relationships? To know someone from thousands of years, how might that inform the way they stand beside each other? Or touch each other? For all the overtures of romance and antagonism that the climax depends on, the depth of those relationships feels oddly slight. In a final battle, two friends become foes. One of them delivers a blow to the other with gusto, “I always wanted to do that”. But why? Little that has come before gives context.

It’s one thing that humanity feels blank—there’s rarely any evidence to support the Eternals earnest love for this race—but it feels like a great curiosity that the actual Eternals feel similarly opaque. And “Eternals” needs that depth if its philosophical crux is to work in context. One imagines that it is Zhao’s reputation for being concerned with those kinds of questions that made her feel as a fitting choice as director, but the overtures of humanistic interest do not manifest in a film that feels as committed to what should be its ethos. Zhao has never been more effective for her ability to balance an ensemble.

It does not help that it all looks too murky and dull especially in the many battle sequences which feel too indistinguishable. Not all the time, but often. The effects are hit and miss and the best realised moments of magic are the conceptualisations of Angelina Jolie’s Thena – the eternal who can form any weapon from the energy around her. These weapons emerge as golden beams around her, and it’s the most visually exciting and portentous visual cue. The role of Thena is thin and any gravity, particularly her relationship with the Don Lee’s Gilgamesh as the strongman of the group – comes more from Jolie than the script. But, it’s interesting to consider how Jolie achieves this by never underplaying Thena’s sliver of an arc. Instead, she plays each moment where Thena is the focus as if it is the most important thing in the world. It’s that commitment alone that makes a mid-film moment of grief work even if it’s plodding in reality.

There are so many arcs, so many styles of characterisations, and so many timelines all clashing with each other. The fact that “Eternals”, like the Eternals, must bear the brunt of galaxies before feels all too fitting. MCU architect Kevin Feige’s approach has been to fashion this universe as the cinematic version of longform television. We are meant to read each film into each other. It is deliberately meant to be connected, and the climax, dependent on the Eternals’ own connectivity, feels like a reminder of that, but it’s that interconnectedness that the film asks for that is its own enemy. If a perception of holding “Eternals” to a different standard may prove unproductive for some, recognising that the MCU is committed to films that cannot be read on their own feels unavoidable. And these philosophical questions peter out when held against the system of the MCU. So, the implications of an Eternal living a cult-like life with residents in the Amazon, feels waved away. Grand betrayals are then solved by silent tears or knowing looks of understanding. But never really wrestled with.

And a moralistic reading of Eternals feels like a bad way to engage with art, and yet “Eternals” frontloads that kind of morality so you have to read into it. How does a being come into being? Are we more than our memories or can our souls retain our essence without them? There are deeper, thornier philosophical questions on the margins that Zhao approaches and then scuttles away from in retreat. The film cannot bear the weight of it. So, robbed of speech, so much time is spent with meaningful glances that must bear the weight of millennia. Even the most expressive actor would be felled by that responsibility, and woe to the “Eternals” that its cast – well-meaning and lovely to look at – buckle under that weight.

Chan has a gentle charisma that works in the romance comedic bits, but must spin too much out from Sersi. But her gentleness becomes frustrating when it plays out in later moments that require different temperance. But it’s not so much her but that everyone is playing a type. It becomes too rote. Extra-terrestrial beings with all the sentience one can imagine but limited by types with little nuance. Madden is doing the most with his characterisation, the least discernible type and faced with a gargantuan emotional turn in the final third that – doesn’t quite work? It’s not so much that he’s out of his depth but the film is depending on creating characterisations from so little it’s impressive for how committed he is to the way the character unravels. It makes sense that the least fussy performance is Kit Harrington, who appears in the film in the moments divorced from the weight of 7000 years. He shows a capacity for anxious humour that feels lived-in and earnest. And Jolie, confidently existing in her own cosmic space as Thena, works on her own but in context feels too worldly and knowing for the rest of the group. She seems too good for this.

Much has been made of Zhao’s decision to shoot much of the film on location – we move from Brazil to Iraq to North Dakota to London to Australia and the locations look good, in the moments we get to engage with the natural world. But in too many moments, the effects feel incongruous with them. As if the film cannot quite settle into a particular look or tone, but instead exploring a surface level geographical traipse through the world. Which makes sense for the limits of “Eternals”. In snatches, it gives us a genuine moment of visual specificity that works but it cannot keep up the weight of all the questions and implications that it depends on. It’s hard work for ten people to hold up a world, and it’s hard for one film to hold up a universe if the universe is the MCU. If it must be all things to everyone, then it ends up being little unto itself. A chain in the larger cosmos, important for what it projects but less effective for what it is, or could be.