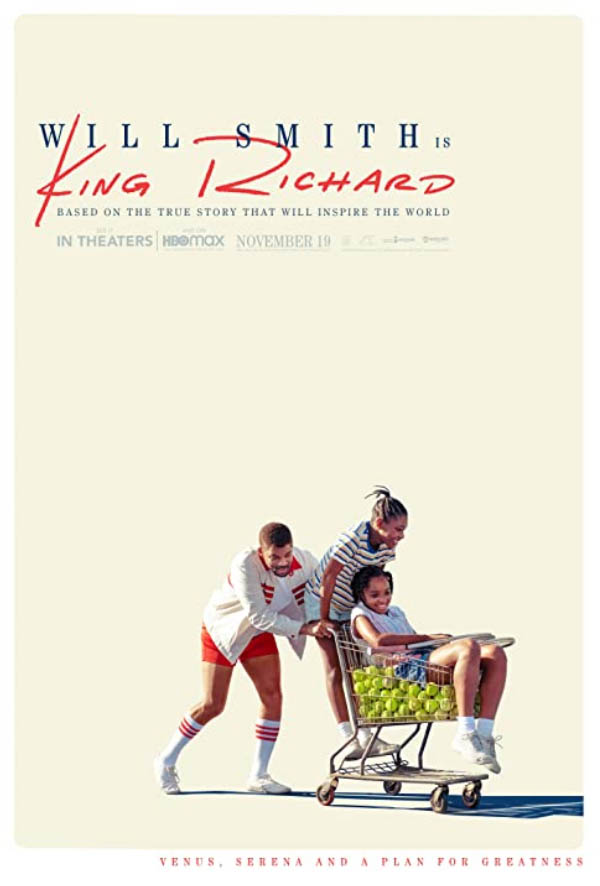

The theatrical poster for “King Richard” introduces us to an important discrepancy. On it, we have the title of the film, loaded with significance, hovering over an image of a man pushing two young girls and numerous tennis balls in a shopping cart. The man is Richard Williams (as played by Will Smith), the two girls are his daughters – Serena (Demi Singleton) and Venus (Saniyya Sidney). The two girls will go on to change the course of tennis, and their father contributions are a big part of that. The image seems to refute the title, though. In it, the king is performing service. The girls show no fealty to any king here; they are caught up in their own happiness. It’s a small thing, but it’s a kind of telling incongruity that the actual film will play around with. And it’s an incongruity that the story itself must wrestle with.

“King Richard” is not just a sports film but it’s a quasi-biopic centred on the early years of two girls who would grow up to be great, and the man that shaped their early years. By all accounts, Richard Williams was tough on them, to good effect and, sometimes, not. He is a mercurial figure who is inherently complicated. How could that kind of complication fare in film produced by the family, though? What kind of authorial distance might even come from a film that immediately emerges as a family tribute rather than a removed investigation? And so, we read that knowledge into the film itself. What here is truth or illusion? And how much truth do we require from this fictionalised narrative film, anyway?

It feels unsurprising that, despite generally positive responses, critiques of “King Richard” have been preoccupied with the lens of an autocratic man as the centre for a story about two legendary women. Why elide the significance of these women by turning this into a story of a man? In some ways the film itself is responsible for – the title itself announces his supremacy. And yet, from the poster itself that illusion of greatness feels more uncertain.

A film is more than its surface. Reinaldo Marcus Green’s “King Richard” might appear as straight-forward sports tale tracing the beginnings of dual tennis legacies but its title is interrogative. Reading a film, really seeing the nuances at work, depends on reading beyond perceptions of the centre and really examining how it all comes together (or doesn’t). This kind of active reading feels critical to “King Richard” which asks you to read many, sometimes conflicting things, in (and outside) its frames. From reading through the film’s marketing of itself, to its presentations of itself and then pulling at the threads that converge, then diverge, in ways that create something more complicated and even ambivalent than a first glance might suggest.

Smith’s voice is the first thing we hear, adopting the Southern drawl to typify Richard. “Where I grow up, Louisiana, Cedar Grove, tennis was not a game peoples played. We was too busy running from the Klan. But here it is. When I’m interested in a thing, I learn it.” We are introduced to him scavenging at tennis courts – collecting stray balls, ingratiating himself to the workers and soliciting potential coaches for his daughters. The monologue is part of a rehearsed pitch he adopts as part of his performance – all in service of getting his daughters what they need to succeed. It’s an intriguing, and even compelling rift. And, yet, it’s a bit of a false start for a movie that kicks into gear later on. You recognise from the onset that Zach Baylin’s script is working with Green’s direction to subvert our expectations of Richard’s public and private life. But the opening sequences belabour their responsibility of setting up the stakes: There is our introduction to Venus and Serena is a joking competition to see who can carry the most phonebooks; and our first meeting with an inquisitive neighbour who will be a foil for Richard’s idea of family; and a group of hip-hop playing youths who threaten the peaceable equilibrium that Richard tries to curate at the barren community court where the family practice. These all feel too dutiful at first. Slightly self-conscious, but an important set up is happening here. From its inception, the real centre of the film isn’t Richard really but the entire Williams family.

Things kick into gear properly in the first act when Richard gently bullies free coaching from Paul Cohen. But Cohen can’t commit to two, and so it’s only Venus who can earn this time with the first real tennis coach for the family. As she goes off to practice, Serena dejectedly walks into the house, her mother (an excellent Aunjanue Ellis is the film’s MVP as Brandy Williams), says, “I know you’re feeling left out. But you’re not left out.” The line feels like a self-conscious observation in a way but it works. There are five daughters in the family, and the strongest sequences are the one where the parents and the children all juggle with each other. It means something that Green’s direction feels most confident in these moments where plot is incidental and we luxuriate in the tensions of these familial interactions. In that moment, Brandy intentionally pulls our focus when she tells Serena, “You’ve got something great too. Me!” In the next sequence we cut between Venus at practice with Richard and Paul, and Brandy with Serena. It’s true, the film might do better centring the duality in parenting perspectives. In critiquing Richard’s insistence on centring himself within the family, the film falls prey to that centring but it’s counterintuitive to watch “King Richard” and not recognise the way it’s much more thoughtful about its presumed protagonist.

A quick succession of scenes follow that recalibrate our idea of what’s really going on here. About fifty minutes in, Venus experiences her first taste of public success at the game. The girls celebrate in the back of the van to the delight of their mother and the consternation of their father. He’s concerned about their bragging, and briefly drives off as the girls celebrate with five dollars in a convenience store. His plan is to leave them to walk three miles home as punishment. He begins to make his case for this and Brandy interrupts. “Why is it that you gotta ruin everybody else’s day? You don’t wanna be happy, so you don’t want anyone else to be happy.” The argument fades out intermittently, and we cut away from them to the girls on the street – it’s intriguing how the argument feels both critical, but also elided. Brandy gets her way, no one is leaving her girls on the street. But the moment is resolved. In the next scene, Richard is still smarting at his foiled lesson. He makes them watch Disney’s “Cinderella” to ensure they get the message. If you’re not humble then you’ll never succeed. The girls don’t really get it. They protest. Brandy is mostly silent, except for a few lines of protest. But the camera keeps coming back to her. Seething. It’s as if there’s a boomerang in effect. Richard is talking but the camera keeps bouncing back to her. Grimacing. Sighing. Building. Finally, mercifully, he lets the girl escape. Ellis turns to Smith with intentionality. “You feel good about yourself?” And then we return to that threat from the previous scene. “Never drive off without my kids again.” It’s a warning and a threat. She walks off leaving him to dejectedly shake his head. Something is amiss here. Even as “King Richard” is ambivalent about exploring that tension, the film itself is invoking it. It’s been perplexing to read many argue that the film fails because it never explores the women. If a film is teaching us to read it, it is also teaching us to look beyond the margin of Richard. So, a few scenes later when he rails at some social workers who are called on a complaint of the children being mistreated, the coda to the scene is not him railing but a taut conversation between Brandy and that very neighbour.

There is a note of the muddle in the narrative, especially in the middle where it follows a biopic staple of this happening and then that happening and then that other thing happening. The stories keep straining against themselves, reaching for something more propulsive. It finds that propulsion, luckily, in the tennis matches which are shot with notes of tension that interrupt the sunniness of the cinematography elsewhere. Here, tennis feels like something anxious.

Where “King Richard” feels disjointed is with Smith, who never feels completely comfortable surrendering to the smallness the role of Richard requires. In a late scene, the moment of release for Brandy where Ellis gives full voice to her exhaustion, she cuts through him like a knife. It’s important that this moment takes us into the film’s last arc, where Richard fades. But, in this moment where she all but calls him a coward, the film struggles against its players. Smith, the star, cannot disappear for the character to take over. The script tells us about these moments and lines of dialogues suggest it. But he’s never willing to really embrace the meanness, the pettiness, the rancour, the cowardice. He is dependable, sometimes even good, his performance problematises never settles. It’s the nature of stardom. Smith’s Richard never coalesces into a clearly discernible figure. The rest of the cast is carving great depths, even when their characters are not at the centre of specific scenes. Singleton’s youthful joy for her sister and her uncertain resentment. Sidney’s capacity for warmth and tenacity. Ellis’ eyes watching everything, her face becoming the audience’s context for every decision. But when Richard is not the focal point, Smith feels lost. And when he is the focal point, he’s earnest but consistent. And we need to see him building the arc of a man realising that he is not a king, but a Queenmaker. The script gets it, Smith less so.

The final moment before the credits is instructive. A crowd of supporters congregate, shouting the name “Venus”. The young Venus runs and hugs Serena as their mother walks beside. They walk away from the camera, with Richard trailing behind – the camera draws out from them and we watch from a distance. And then, Richard’s voice joins in with the throng and we hear him, “Venus! Venus!” And we close. The film itself is a meticulous deconstruction of that kingship. Not in a tragic way. But it’s really about succession. It’s why the film ends before her true professional career success. We know the “after” of the story; the film is the before. And it works, even with the discomforts and ambivalences. Even when it falters, it’s given you the tools to read the nuance in the margins. But the tale of Venus, and Serena are so legendary why do we assume this is the last word on it? Why do we expect that their legacies are closed? Is it that we cannot imagine a story of two Black women having enough material for more than one artistic work? There are dozens of stories about so many other greats—why do we expect King Richard to be the last word on these women? That it does not meet the heights of their professional career might be an interesting query but then one wonders, why and how could it? It ends before any of them earns a WTA victory. This isn’t that story. “King Richard” knows that it’s not telling that story, and it’s teaching us to read into why it doesn’t. it’s not entirely successful but it’s thoughtful about itself in some compelling ways. It feels ironically fitting that the actor portraying this not-quite-a-King becomes the films real liability, but there’s much here to value. Even when it falters, “King Richard” demands attention.

King Richard begins playing on December 2 in local theatres