The use of intelligence services was an important strategy employed by Britain to supress anti-colonialism in the Caribbean. One example of this can be clearly seen in its overthrow of the legitimately and democratically elected government of British Guiana in 1953. Secret service records of the British spy agencies are held in the British National Archives in London. From time to time, records are declassified from ‘Top Secret’ status and made available to the public because its contents are no longer considered sufficiently sensitive, or a risk due to the passage of time. This article provides some insight into the intense spying activities that surrounded the deposed British Guiana leaders Cheddi Jagan, and Forbes Burnham by British spies when they visited Britain in October 1953 to protest the overthrow of the British Guiana government by Britain.

Resistance and rebellion against British rule, and the economic impact of European wars and the economic crash of 1929, intensified in the 1930s in British Guiana. Strikes, demonstrations and uprisings, particularly focused in Georgetown, the capital city, drove the emergence of new political directions. Trade unionism, the rise of Communism in the Soviet Union after 1917 and its pledge to support the liberation of black people with an anti-colonial programme, fed into the new political consciousness of young radicals in Guiana. Cheddi Jagan (1918 – 1997), the son of former Indian indentured workers, returned to British Guiana in 1934, from the USA where he qualified as a dentist, with a dream to lead British Guiana to freedom. He had married Janet Jagan (1920 – 2009), a white American dental nurse who was a committed Marxist, and she joined her husband in what was to become a high profile political journey over many decades. Forbes Burnham (1923 – 1985) was an ambitious British educated lawyer of African origin, who returned to British Guiana following his education. He joined forces with Cheddi Jagan to form the original People’s Progressive Party (PPP) with a programme of anti-colonialism and essentially to form a multi-racial coalition prioritising the freedom from colonial rule and the uplifting of the working people.

In the general election, held in April 1953, the PPP won an overwhelming victory, succeeding in 18 of 24 seats. This victory was short-lived as the British Government declared in October 1953 that the PPP government was dangerous and seeking to establish a Communist State and suspended the Constitution. British troops were sent to British Guiana and a four-year period of repression was introduced with the declaration of a State of Emergency and the imposition of martial law. Many of the PPP’s leaders and activists were imprisoned for breach of the new regulations (for example by meeting with others, holding demonstrations, printing and writing communications), and restriction orders requiring them not to leave defined geographic locations. Cheddi and Janet Jagan were imprisoned, along with other leading PPP officials including Rory Westmaas, Eric Huntley and Eusi Kwayana. This intervention by Britain is often associated with the creation of political instability in Guyana that has endured into the contemporary period.

Immediate surveillance

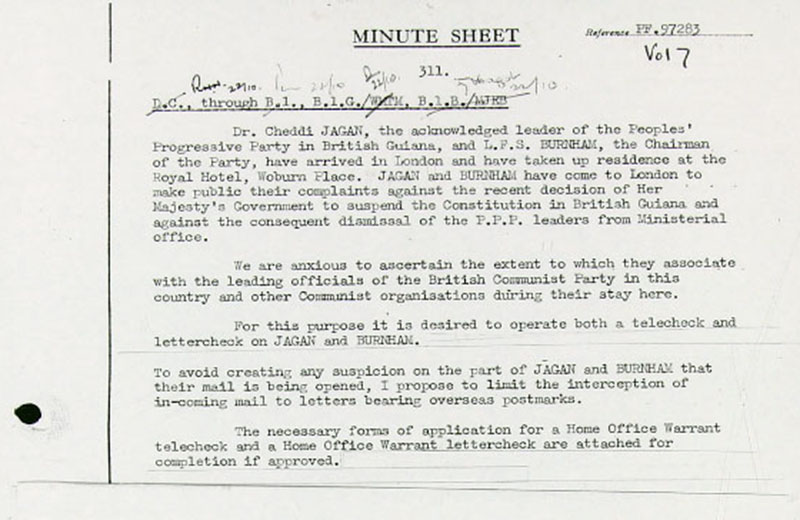

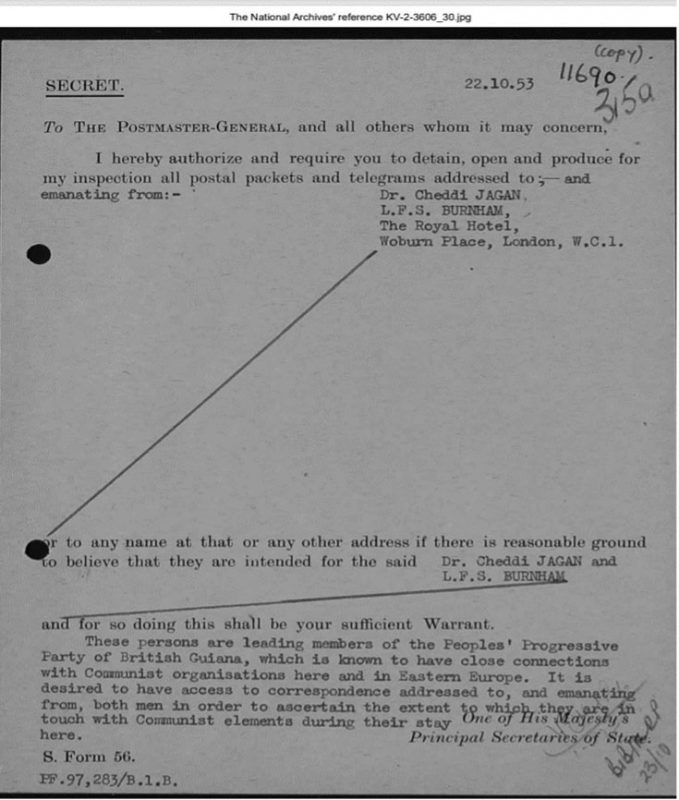

In October 1953, Jagan and Burnham travelled to Britain to protest the suspension of the Constitution and inform the British public of the impact of the crisis. From the moment the two leaders landed in Britain, they were placed under immediate and intense surveillance, followed from the airport, and then for the remainder of their trip. The reasons for the surveillance was to provide justification for the suspension of the Constitution, particularly any association with the British Communist Party and other Communist leaders. It was carried out through the interception and opening of the leaders’ correspondence, and the tapping of their telephone calls. Extract 1 shows an authorisation to the Post-Master General to ‘detain, open and produce for inspection all postal packets and telegrams’ addressed to Jagan and Burnham at the Royal Hotel, which is where the pair travelled to directly from the airport.

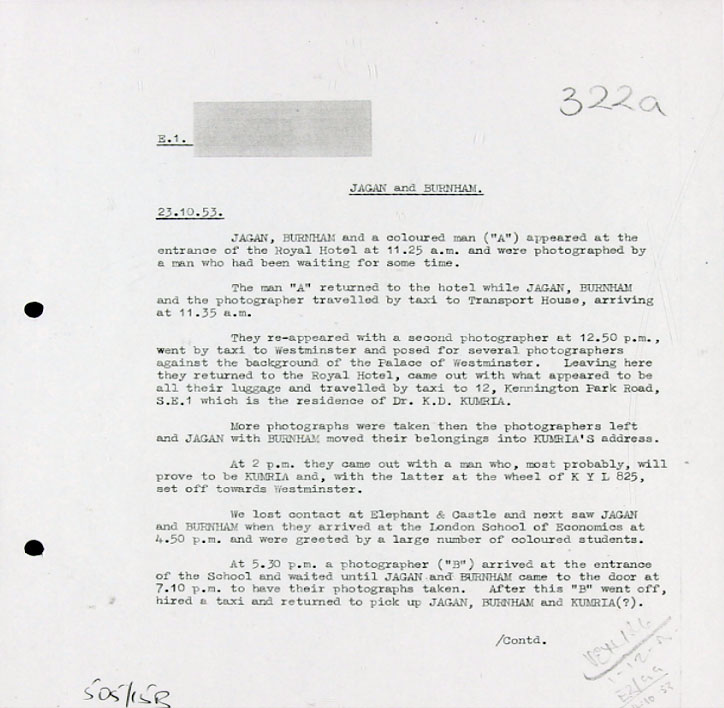

It is not known the extent to which private organisations, such as the Royal Hotel, co-operated with the security services in the surveillance of the leaders. This co-operation, which may have been legally compelled, would presumably have been required to facilitate aspects of the surveillance. It is noteworthy that they stayed at the hotel for a short period prior to moving to the private home of an associate Dr K.D Kumria. Kumria was the General Secretary of the Council for Indians Abroad and founder of the Swaraj House, a meeting place for Indian political activism in London. He was also an associate of George Padmore, the Trinidadian radical and intellectual.

It is unclear whether Jagan and Burnham were aware of the surveillance, but that is probable given that they both completed higher education and professional training in Western countries. They were subjects of surveillance by British security services in British Guiana for years prior to the general election of 1953.

Extract 2 lays bare the determination of the British government to uncover evidence that the two leaders were Communist sympathisers, against British interests. The interception order states: ‘We are anxious to ascertain the extent to which they associate with leading officials of the British Communist Party in this country and other Communist organisations during their stay. For this purpose, it is desired to operate both a telecheck and lettercheck on Jagan and Burnham’. In order to avoid raising the leaders’ suspicion that their letters were being opened, the security services decided to restrict the interception of correspondence to the letters that arrived from overseas.

In the public eye

Jagan and Burnham’s visit attracted a strong media interest.

They were photographed and filmed wherever they went, underlining the success of the purpose of their visit. Far from holding secretive meetings with the Communist Party or others deemed of interest to British security services. The documents show that the leaders were in fact very much in the public eye, and attended high profile venues, such as the London School of Economics (Extract 3).

This visit also informs of the presence of black students in Britain during this period, and their level of interest in, and knowledge of the activities of Britain in its colonies. They turned out in large numbers to hear the British Guiana leaders speak. Extract 3 describes the arrival of the two leaders to speak at the London School of Economics ‘where they were greeted by a large number of coloured students’. As people who were not white were described as ‘coloured’ during this period, there is no detail of the ethnic background of these students, but it does suggest the extent of interest and support for the British Guiana leaders from Caribbean people abroad.

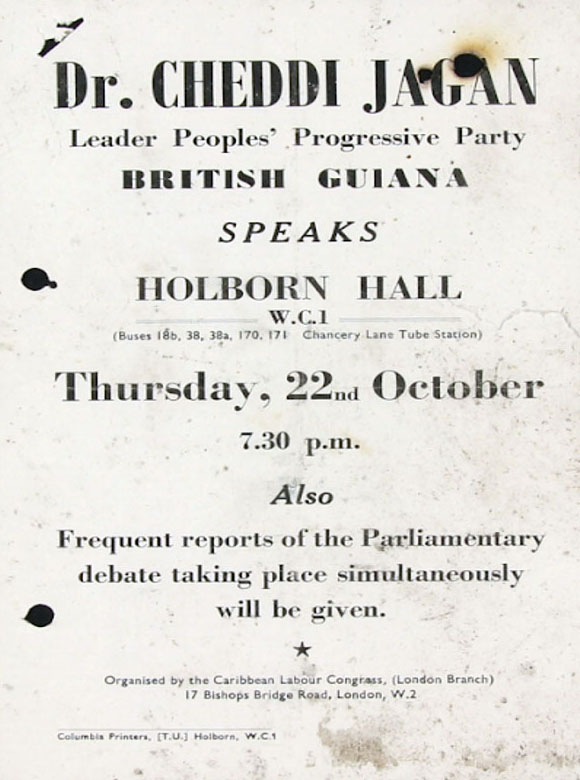

The security services tried to anticipate the leaders’ movements in order to maintain what appears have been desperate and sometime unsuccessful pursuit of them. They simultaneously covered potential venues, including the hotel and the House of Commons. The British Guiana debate, to determine whether Britain had been justified in suspending the Constitution, was held in the Commons on 22 October 1953 and the security services operated a surveillance exercise in the public gallery but found it a ‘hopeless’ effort to identify whether the leaders were there due to the gallery being packed by ‘many coloured men’ (Extract 6). On the same date, Jagan and Burnham appeared at Holborn Hall, a public venue. The flyer for this event shown in Extract 7, states, ‘Frequent reports of the Parliamentary debate taking place simultaneously will be given’. It is of interest that the British security services sent spies to the Commons to observe for the presence of Burnham and Jagan there when they were at an advertised public forum in Holborn. This shows the failure of the security services on this aspect of the surveillance. The crisis in Guiana generated so much interest in Britain among the black population, presumably the Caribbean student population, but perhaps the migrant community as well. This description also provides a picture of the pre-dominance of black men in the political activism in Britain at this time with an invisibility of women, either in actual numbers or failure to acknowledge the presence of black women in the Commons’ gallery.

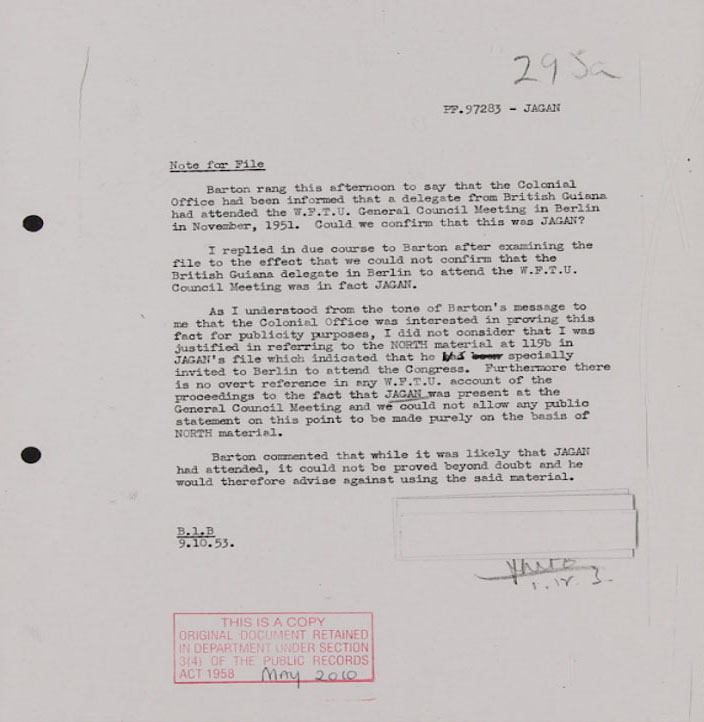

During the leaders’ stay in Britain, the security services also conducted enquiries about their involvement and affiliation with earlier trade union activism in Eastern European communist states. The World Federation of Trades Union held a conference in Berlin in 1951 with a delegate from British Guiana and the security services were trying to ascertain whether this was Jagan, to provide evidence of his dangerous communist affiliation, and justification for the repression, and to use this information for ‘publicity purposes’, indicating the great pressure to discredit the political reputation of Jagan (Extract 5).

The records of the British security services form a valuable part of the history of colonial activity in the Caribbean, and documentary evidence of forms of resistance. The records discussed in this article, focusing on the case of Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham’s visit to London, provide additional data to study how Britain utilised its secret services to maintain its interests in its Empire. The paucity of evidence in these records to justify its claim that Jagan and Burnham were planning to turn British Guiana into a Communist state underlines fear mongering about communist ideology, which was important to all black activists at the time.

These records are also important because of activity in Britain to ensure their destruction and to erase evidence of British colonial crimes. The intensification in concern for uncovering truths about black history and the black struggle in the wake of the murder of George Floyd places an added imperative on scholars, and others, to seek to fully document black history and explore records such as presented in this discussion.

Claudia Tomlinson, who is Guyanese by descent, is a London-based scholar specialising in Guyanese and Caribbean British History. A previous version of this article was published in History Matters Journal, Volume 1, Summer 2021.

Background Reading

Associated Press, ‘MI5 Files Reveal Details of 1953 Coup That Overthrew British Guiana’s Leaders | Guyana | The Guardian’, 2011 <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/aug/26/mi5-files-coup-british-guiana> [accessed 11 April 2021]

Chandra Jayawardena, Conflict and Solidarity in a Guianese Plantation, London School of Economics Monographs on Social Anthropology (Oxford and New York: Berg), xxv

‘Dr Cheddi Berret JAGAN / Janet Rosalie JAGAN: British. Husband and Wife and Leading Political Figures in British Guiana.’, 1953, National Archives, Records of the Security Service.

Francis, Berl, ‘Forbes Burnham (1923-1985)’, 2015 <https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/burnham-forbes-1923-1985/> [accessed 1 May 2021]

Gaiutra Bahadur, ‘In 1953, Britain Openly Removed an Elected Government, with Tragic Consequences’, 2020 <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/oct/30/1953-britain-guyana> [accessed 11 April 2021]

Gregor Davey, ‘Intelligence and British Decolonisation The Development of an Imperial Intelligence System in the Late Colonial Period 1944- 1966’ (Kings College London, 2014)

Holly Wallis, ‘British Colonial Files Released Following Legal Challenge’, BBC News, 2012 <https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-17734735> [accessed 2 May 2021]

Ian Cobain, Owen Bowcott, and Richard Norton-Taylor, ‘Britain Destroyed Records of Colonial Crimes | National Archives | The Guardian’, 2012 <https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2012/apr/18/britain-destroyed-records-colonial-crimes> [accessed 2 May 2021]

Maya Jasanoff, ‘Misremembering the British Empire | The New Yorker’, 2020 <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/11/02/misremembering-the-british-empire> [accessed 2 May 2021]

Nehusi, Kimani S. K., A People’s Political History of Guyana, 1838-1964 (Hertford: Hansib Publications, 2018) <http://capitadiscovery.co.uk/chi-ac/items/526376>

Rodney, Walter, A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881-1905 / Walter Rodney (Kingston, Jamaica: Kingston, Jamaica)

———, ‘Plantation Society in Guyana’, Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 4.4 (1981), 643–66 <www.jstor.org/stable/40240885>

‘The Open University, Making Britain, Discover How South Asians Shaped the Nation (1870 – 1950), George Padmore | Making Britain’ <http://www.open.ac.uk/researchprojects/makingbritain/content/george-padmore> [accessed 2 May 2021]

‘The Open University, Swaraj House | Making Britain Discover How South Asians Shaped the Nation (1870 – 1950)’ <http://www.open.ac.uk/researchprojects/makingbritain/content/swaraj-house> [accessed 2 May 2021]