For all the things that might be said about Guillermo del Toro’s latest film, I’d be surprised to hear anyone say it’s anything less than consistently engaging. “Nightmare Alley” is an adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel, best remembered for the 1947 film adaptation with Tyrone Power as the charismatic Stan Carlisle. In this new version, Bradley Cooper is our Stan, an ambitious carnival worker who tries to outrun his murky past to launch himself into a cosmopolitan life of success. He succeeds and then fails and then he does both, in a way. This is no spoiler. It is a tale as old as time: A cavalier grifter begins to grift and slowly grifts himself into a corner he can’t get out of. Is anything here new? Unlikely. I’m not even sure del Toro is trying to surprise us; he’s doing his damnedest to telegraph the worst of this reality from the early moments. But that we get swept up in the hopes and desires of these small people is as much as testament to him and to the way he’s curated the film’s sensibilities in line with this grimly beautiful dreamscape. And in this perfectly designed world of dramatic set-pieces, it’s Cate Blanchett and Toni Collette as two versions of potentially dangerous women that are the best realised, as they are attuned to the performative charms of women doing what they can in a hopeless world.

The film is a slight shift for del Toro, who tends to be more concerned with supernatural monsters. Here, the monsters are all human and in this world tragedy and disaster are assured from the onset. We would be fools to hope for something else. The screenplay, co-written with Kim Morgan, is an important sign of the intentionality at work from del Toro here and every frame of the gorgeously photographed film is in support of this. It’s so specific about its intentions, so proficiently imagined with a clarity of sound and visual language to conjure the seediness of its world that I found myself momentarily surprised when its final, bleak moment, didn’t hit me with the shock I would have imagined. But it’s a credit to the filmmaking that despite not being surprising within the film, the malevolence of it has lingered.

Indeed, “Nightmare Alley” is at every turn more intentional and more explicit than one might necessarily anticipate or even wish. “Didn’t you notice my clutch was heavy?” A repeated line late in the film signals an important twist, although twist seems inexact considering how precisely everything is set up here. Yes. del Toro is using his familiar framework of emblazoned symbolism with every deceit and every result foreshadowed to us early on. TAKE A LOOK AT YOURSELF! SINNER! LUST! These words are emblazoned in the foreground juxtaposed with an image of Bradley Cooper that lends a slow-churning inevitability to everything. And the final scene, when it does come with the subtlety of a blow to the head, assures us of this. But subtlety isn’t always for the best, or even needed. The heaviness is all intentional. It’s overwhelming. It’s draining. It’s striking. It’s never quite sad, though, and in an important shift del Toro seems consistently removed from the emotions of these characters. The closest thing to humanity is a brief sequence with an excellent Mary Steenburgen in a brief role. And I wonder as to del Toro’s inclinations here in front-loading the inevitability of doom. I prefer del Toro when he’s a little more tender, a little gentler, like in the fragile hope he gives us in “The Shape of Water”, but the surety of despair in the good/evil battles of “Nightmare Alley” have their benefits, too.

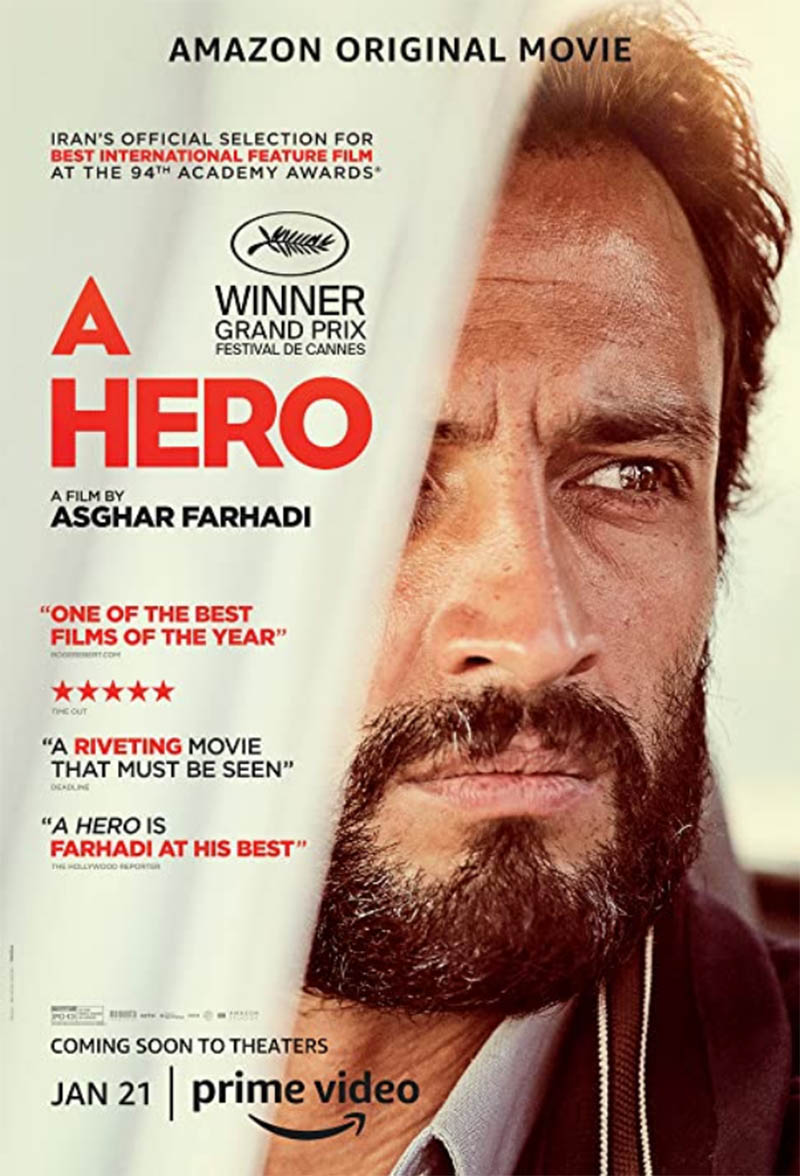

Although the ornate circus delights of “Nightmare Alley” might seem far removed from the realistic Iranian streets of “A Hero”, I’ve been thinking about the intentional explicitness of Asghar Farhadi’s work in relation to del Toro’s. “A Hero” was unfortunately missing from the recently announced list of Oscar nominees for Best International Film. Currently in streaming release, “A Hero” feels like a bleak and rewarding entry to juxtapose with the differently bleak scope of “Nightmare Alley”. In “A Hero”, Rahim Soltani is a prisoner enjoying a few days of leave from a long-term sentence for an unpaid debt to his former brother-in-law. The leave promises to be something even more hopeful when his girlfriend shares a handbag she’s found with several gold coins, perhaps a stroke of good fortune to pay off the debt and have him released. But the price of gold has depreciated and Rahim decides to turn the bag in for its owner to find. The good deed brings success, good publicity an increased chance of release. But nothing gold can stay, and soon the good leads to the bad and then the worse. The devil, like any Farhadi film, is in the details and the half-truths, equivocations and well-intentioned lies upend any hope for Rahim and his family.

Farhadi’s work has been habitually distinctive for its intricate plots, the labyrinths of bad decisions leading characters down a path of unavoidable despair. “A Hero” is no different and is perhaps only bleaker for the ways the sense of isolation feels inherent to Rahim, who is so constantly alone, even when surrounded by others. The modesty of this world is far removed from the grandiosity of the carnival and big-city settings in “Nightmare Alley”, but Farhadi’s concerns echo the focus on legacy there. Both films find their strongest moments in reminding us, dismally, that we can never outrun our past. Rahim’s antagonistic ex-brother-in-law is introduced unpleasantly and, with our allegiance tied to Rahim, we are mistrustful of him. Although he never becomes less antagonistic, as the film goes on, we begin to recognise how even those we might despise in action and thoughts are carrying their own weight and scars. If only we could spare a little empathy. But it’s hard to spare empathy when your life feels so stultifying. And so, the moments of true heroism in “A Hero” feel moving for their earnestness, but sad for the way an unfeeling society is predisposed to never truly recognise it. If Farhadi and del Toro believe in anything, it is that the world is ultimately bleak and unrewarding. We do what we can as we await our fated ends. But “A Hero” feels more complex, and more rewarding, even in its bleakness, for the way it feels so firmly attuned to the man at its centre.

A lot of this is owed to Amir Jadidi as Rahim, in one of the best film performances of 2021. He’s threading a very fragile line in “A Hero”, the title of the film a mocking warning and repudiation. It is important that Rahim immediately convinces us that he is, generally, a congenial fellow. But it’s also important that his desperate acts of goodness seem like something more than just selfless acts of unrealistic goodness. Hayedeh Safiyari’s editing also performs an impressive formal trick in its expertly constructed sequence. Formally, “A Hero” keeps tricking us into thinking this isn’t as tragic as it seems, with specific cuts encouraging us to find possible solutions within the frames even as the actual story feels as if it’s hastening to something less hopeful. The final moments of “A Hero” are muted and melancholic, a disarming realisation that hope and good intentions cannot always build success. Society is rotten, and faced with that we reality we can struggle against our fate to make the most out of an unhappy lot but we remain bound by forces beyond our control.

“Nightmare Alley” is streaming on HBO Max and “A Hero” is currently available on Prime Video.