Introduction

Today’s column and next week’s will address the first of six broad strategic policy choices or actions that I propose the Authorities satisfy before the mid-2020s. That policy choice is my revisit of earlier recommendations [2018/2020] to establish a National Oil Company, NOC. As stipulated in the Analytical Schema, the list of items to be revisited make up Pillars C and D; namely, 1) an NOC; 2) whether to join OPEC or the OPEC+ cartel; 3) domestic legislation governing Local Content Requirements, LCRs; 4) Policy for Investment in Renewables; and 5) the overarching themes of Governance & Revenue Capture.

National Oil Company

Given a policy option as to whether or not Guyana should establish by the end of the 2020s an NOC, my recommendation remains emphatically, yes! As readers full well know, ExxonMobil and partners presently dominate oil and gas operations, decision-making, along with control of all critical control points along the value chain of Guyana’s oil and gas sector. Indeed, I predict this profile will remain more or less intact during the coming decade, if left un-addressed directly. Further, I predict, confidently as well, that the most likely outcome will be only greater variation in the nationalities of the foreign corporations which are in control. Such a bleak outcome convinces me that it is only an NOC which can alter this dynamic.

My longstanding call for an NOC in Guyana was initially raised in connection with the public debates about whether Guyana should build a state-owned oil refinery. I had participated in those debates, when the Pedro Haas feasibility study on a project commissioned by the Government of Guyana (GoG) was presented and debated three years ago. I had strongly rejected the idea at the time. Readers would recall also the Haas study had found such a refinery to be too risky, too costly, too expensive and hopelessly uneconomic. Moreover, global trends then revealed a growing surplus of refinery capacity, which made the idea even more ill-advised.

It should also be recalled that this issue was further appraised by a GoG Advisor from Chatham House, London (V. Marcel). She had advised the establishment of a National Energy Company in order to embrace Guyana’s thrust in favour of renewable energy. Parenthetically, the IMF had recommended in this period the formation of a State Holding Company.

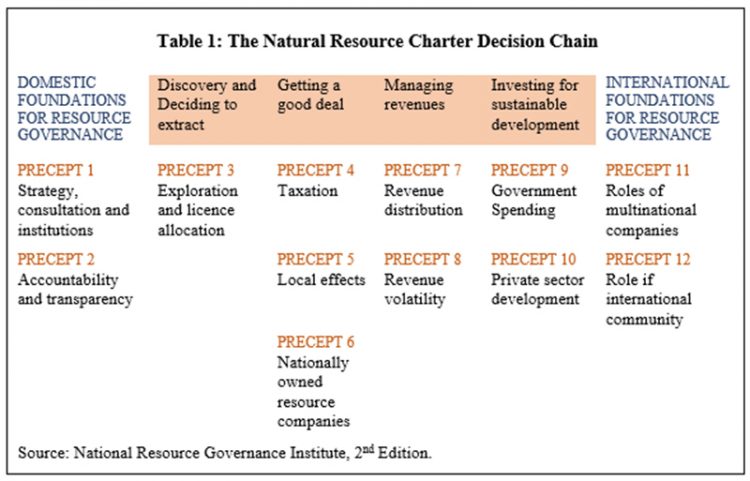

For myself, I had advocated a NOC along the lines proposed in Precept 6 of the Natural Resources Governance Institute’s, NRGI, Governance Charter

NRGI

The starting point of the NRGI precepts is the portrayal of NOCs as pivotal components for harnessing a country’s development potential arising from the discovery of oil and gas resources. They are therefore designed to yield several benefits; namely, 1) to capture as much as is economically efficient of the economic rent yielded by the petroleum potential; 2) to balance the trade-off between state benefits capture and losses incurred by deterring private investment; 3) to recognize that taxes cannot capture all potential economic rent; 4) to offer a means whereby technology can be transferred from the operating IOCs (particularly in the offshore sector) to local businesses and investors; and, finally, 5) a similar facilitation in the form of “transfer of “efficient business practices” to local commercial entities and entrepreneurs

The existence of an NOC also reduces the information asymmetry, which bedevils operations of IOCs in poor countries. It has been long recognised universally that, when information is widely lacking, then the best use of resources is most unlikely. Information is therefore crucial to the efficient commercial and economic use of Guyana’s oil and gas resources. An NOC always facilitates the flow of requisite information.

The above considerations bring further immeasurable benefits. Using my earlier metaphor, an NOC gives Guyana the proverbial “seat-at-the-table” of decision-making in regard to the pace and disposition of its natural resources. This means direct influence in operational decision making in the sector. With a seat at the Table, Guyana is positioned to influence upstream petroleum sector outcomes and therefore yield benefits from a local content policy and the construction of domestic linkages within the oil and gas sector, and between that sector and the non-petroleum sectors of Guyana.

Conclusion

As will be discussed next week, the recommendation in favour of an NOC has evoked great controversy. Not surprisingly, the controversy has reflected, perhaps unintendedly thus far, the different development paradigms and praxes at stake in the debates. Indicating extremes, one pole prioritises the need to 1) constrain foreign dependence and control over natural resource exploitation, and 2) expand the nation’s influence over its natural resources exploitation. And its polar opposite prioritises 3) expanding the opportunities for markets to guide natural resource exploitations, and 4) confining the roles of government to regulation, monitoring and similar oversight functions.