Handwringing over the running-time of movies ahead of their release is a dangerous game: good movies feel just-right, regardless of their length and lesser movies feel long, overstaying their welcome, no matter how brief. “Bullet Train” is not a very good movie, although there are occasional flourishes that suggest something better lurking inside. Its liability, though, is an inclination towards over-explanation and convolutedness that feels antithetical to the genre its working in albeit in line with a contemporary approach to “humour” that wears its welcome out. It is an action/comedy/thriller after all. Surely brevity and propulsion are essential? And although the film sometimes promises forward movement, it very often finds itself giving into its worse impulses, cutting of a great punchline at the kneecaps.

There’s a late scene that epitomises this. Towards the film’s climax, two figures face-off in the aisle of a train; one is pointing a gun at the other. Earlier, that same gun was rigged to create an incongruous effect when the trigger is pulled. Like any contemporary action film, guns abound in “Bullet Train”. But this specific gun has been designed in a way to make it identifiable, and the sequence of events that leads to the moment is reminder enough for us to wait – with bated breath – for the imminent events to ensue. Except, rather than letting it play out there’s a brief sequence where the camera travels into the barrel of the gun, showing us the internal rejigging. It only lasts a few seconds, but it’s indicative of a larger looming dichotomy in “Bullet Train”. In theory, this is a one-setting, one-day film – a series of assassins, and criminals, are trapped on a speeding train headed to Kyoto that only stops for 60 seconds at every station. They are all connected to a mysterious figure – a powerful yakuza boss known only as “The White Death”.

The set-up provides audience with something that announces immediacy and energy. But, Zak Olkewicz’s scriptwriting is much too beholden to context; and not just context-clues. So, the immediacy of the “now” where the train hurtles to its destination is interrupted, and interrupted, (and interrupted) by asides – flashbacks, replays of moments we know or think we know, or sequences like that anatomical examination of the gun where a technical flourish that’s fine on its own interrupts the MORE!MORE!MORE! energy that we anticipate from a better version of a film like this. By the time “Bullet Train” begins to wind down, it’s hard not to feel a bit beaten down and worse for wear.

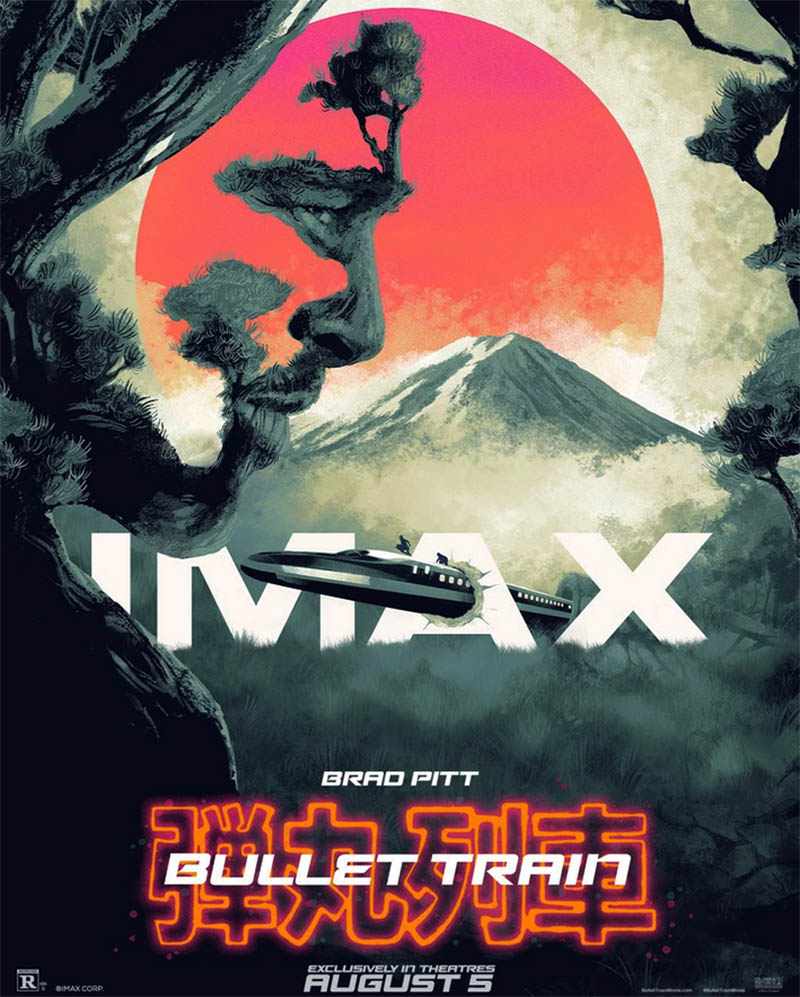

I’ll say this for Olkewicz’s adaptation work in “Bullet Train”: very little in its 126 minutes running-time feels like its adapted from the Japanese novel (“Maria Beetle” or in English “Bullet Train” by Kōtarō Isaka) from 2010, so much so that Westernising most of the characters, while retaining the Japanese setting feels superfluous. “Credit” may go to Olkewicz, or director David Leitch’s tendencies to retain a specific kind of energy in his films. Whatever it is, “Bullet Train” feels like a very Hollywood version of an action-comedy, very often in the worst of ways – and this applies both to the convoluted nature of its “bits” and to its approach to delivering humour. Leitch’s films (“Deadpool 2” and “Atomic Blonde” being among his most notable) tend to beat a dead horse. His sharpest work as a director is “Atomic Blonde”, where he manages to subvert a script that threatens to unravel. But even at his best, his directorial affect privileges a tendency to repeat moments that work so they threaten to become tedious. There’s a winking approach to this – a kind of fourth wall breaking that goes, “See I’m doing that thing again” that quickly devolves from amusing, to tiresome to dull. And it’s an approach that’s frustrating because “Bullet Train” is not without its pleasures.

Brad Pitt’s congenial former assassin is at the centre of the film. Codenamed: Lady Bug, and recently returned from an extended zen-like work vacation, has been asked to stand-in for a colleague on an easy job. All he needs to do is retrieve a suitcase from the train and get off at the next stop. It’s a simple task that, naturally goes awry. The train is filled with personalities that are too connected – Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Brian Tyree Henry as a pair of “twin” assassins delivering a formerly kidnapped man to his father; Andrew Joki (mostly good) as a grieving father trying to find the person who attempted to kill his son; and Joey King (mostly bad) as a sociopathic young killer. These are the main players who are later joined by some additional surprise figures, and a string of cameo figures as the tension heightens, and the hijinks get out of control.

It does feel like a shortcoming that a film set on a highspeed train seems to take no strategic visual approach to presenting that velocity on screen. It’s not quite lazy enough to be considered “by the numbers”, but it never feels engaged with its craft in a way that feels specific enough. If there’s any specific visual language here, it’s in a commitment to covering a cast of good-looking actors in some very questionable hair and makeup choices. “Bullet Train” is flashy, featuring the kind of high-octane editing that is more about creating a spectacle than developing its own identifiable approach to its story and itself. It’s not always a bad thing. In an early flashback sequence, we see the twins kill-count for a job. It’s part of the film’s self-satisfied approach but it’s clever in an obnoxious way that works in brief stretches. In other moments, like a crash sequence where Pitt hurtles through space, the prolonged “isn’t this funny” slow-motion approach feels neither funny nor clever. It’s the quality of the approach in “Deadpool 2” where every potential bit is flung at the audience. Surely something will stick? Yes, and no.

Pitt is fine. He seems to have come off best in reviews, although I’m more ambivalent about the notion that anything here from him feels nuanced enough. He’s never a liability, but his cadence – the straight zen-man to the kookier figures – feels too deliberate to invigorate. The film’s approach to “anti-violence” also feels like a decades old joke that isn’t intriguing: oh, an assassin who has found peace and calm. “Hurt people hurt people,” he tells a criminal late in the film. It’s not clever, it’s just leaden and uninspired. Better, is Aaron Taylor-Johnson, who has achieved a compelling ability to play ridiculousness to good effect. His Tangerine is a messy character, but his physicality in his approach to the humour and action and then pathos feels striking in ways that surprised me. He also has my favourite action sequence, on the back of a moving train that is completely insensible and enjoyable, nonetheless. He’s well paired with Tyree Henry who, even with an unfortunate British accent, are the only relationship in the film that feels genuinely lived in. Joey King’s arc is the worst section. Her British accent is laboured, and a faux-feminist edge to her character is too insipid to entertain. The surprise twist of where her arc leads is especially unsatisfying. Elsewhere, a series of surprise “appearances” interrupt the forward momentum to provide us with some levity to mostly poor results..

The best way I can describe the use of cameos in “Bullet Train” is MCU-esque. Realistically, a cameo in a film that does not greatly affect plot isn’t something that counts as a potential spoiler. But there’s postmodern ironic lilt to the way the cameos play out here. Scene after scene, a surprise “star” appears – here a very straight Hollywood heartthrob playing a very gay, very minor character that the film insists is funny just because; there a big budget Hollywood lead reuniting with a cast member on screen in a last minute surprise that seems built to impress; there a very famous popstar in a role that counters his usual gregariousness and so on, and so on. With each appearance, you can feel the film pause as if expecting thunderous applause for each of these “surprises”. I’ll admit, it began to wear me down. It’s as if “Bullet Train” wanted commendation for mere existence of these cameos than doing anything meaningful with it, and your mileage may vary. By the end, the smirking self-satisfaction was interrupting the potentially charming energy elsewhere. “Bullet Train” isn’t a wasted trip. There’s enough here to be, at least, diverting as it happens. But I wouldn’t board this train again though.

Let’s put Brian Tyree Henry and Aaron Taylor-Johnson on a train together somewhere, and savour in their chemistry though. Sign me up for that trip.