The discussants were listed as “all artists,” presumably those whose work was part of the art exhibition accompanying the event. I modified the topic to “The State of Art in Guyana” and hoped that most of the exhibiting artists would be present to contribute to a vigorous exchange of ideas and a generative discussion. See, our prompt lends itself very well to a litany of complaints, not generative. I was determined to stay clear of the kind of conversation visual artists in Guyana are apt to have when they/we congregate. What needed to emerge from the discussion was a way to be signalled out of the oppressive quagmire of our reality.

“The State of Art” is a very big and broad topic that can be approached without vexation. Was it possible that unconsciously the organisers had closed the pandora box of lamentations about the blasé attitude to visual art by those in authority, the paucity of capital investment in visual artists, and lack of support for them by those with the wherewithal to do differently? I suspected politics, grumblings, maybe even activism in the naming of the topic. But as a practising artist hungry for nourishing conversations about art, I saw scope for conversation that could resuscitate the pulse of my creative heart and perhaps, fuel the burning creative fire in others. I was willing to steer the boat down these waters. I hoped the sailor-artists travelling with me and the passenger-audience on board for the ride would not orchestrate a spontaneous mutiny and take us down waters that would forecast an unpleasant journey. A journey of grumblings and lamentations.

Fortunately, no such mutiny occurred. All involved were delightfully flexible. And from among the sailor-artists, one stepped up to co-pilot our boat. US-based Guyanese artist Arlington Weithers (b 1948) joined the Zoom meeting. Following the first three speakers, Weithers began by sharing the recent successes of fellow US-based Guyanese artist Carl E Hazlewood at Art Basel Miami, the US’s premier art show. Hazlewood was last seen in Guyana judging the Guyana National Visual Art Competition in 2014. At the time of his return, Hazlewood had been away for decades but had remained connected through friendships and significant collaborations with Guyana-based and Guyanese and first-generation artists in the Diaspora. Weithers is one of those artists. Weithers then spoke of his own painting practice and the “call and response” visual dialogues, lived experiences, and technical explorations that have sustained his artmaking. Questions were directed to him by the boat captain as well as others on the journey. Through Weithers’ generosity, our boat had embarked unexpectedly down the river of non-objective painting, the realm of fellow Guyanese artist Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA (b 1934).

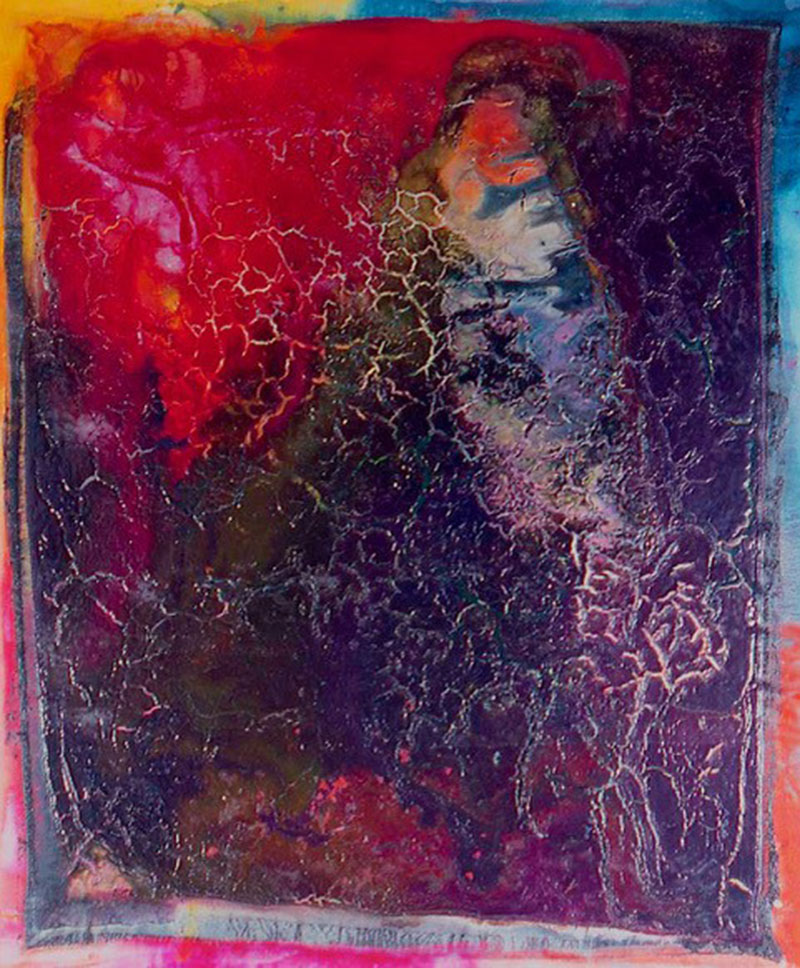

Now, what is non-objective painting? Such painting does not aim to depict persons, places, or things. Instead, some concerns of such painting are colour, shape, texture, and scale. But what does non-objective painting have to do with the state of art in Guyana? Ours is a largely figurative tradition and perhaps these are realms for Guyana-based painters to explore. The assumption is often made that non-objective painting has no relationship with the world of reality. Through his liberal sharing and using his image Thalos Script (1999) as a point of departure, Weithers showed how his canvases relate to his memories of the physical and emotive space of Guyana. He spoke of its existence as a record of his dislocation from Guyana. Weithers left Guyana in 1969. Using this work, he also deconstructed the painting process.

Through Weithers’ generosity of sharing it was repeatedly emphasised that in Guyana we need artist-to-artist conversations that our public can share in – be an audience to. In this way art audiences will gain valuable insight into work that is grounded in decoding a language not based on words. Where possible these conversations need to be intergenerational. It was also made clear that we need artist and art audience conversations that are conducted in public. A great deal can be gained from hearing questions emanating from different perspectives and the responses they garner. And perhaps most importantly, artists and art audiences in Guyana need to see what Guyanese artists are producing in the Diaspora (free from the dictates of national

agendas) so that artists can be nourished and local audiences and administrators can be open to new approaches. On this latter point, it was noted that Guyanese artists abroad are as connected to Guyana as those here who paint obvious nationalistic imagery. However, the visual languages employed allow many to establish meaningful connections with non-Guyanese audiences as well. Thus, their language of connection does not limit the meaning potentials of their work for non-Guyanese audiences and patrons.

From the wider discussion, there were several noteworthy takeaways. I note only a few. Artists in Guyana need to reinvigorate doing for themselves/ourselves, establish productive relationships with institutions (whether place or person), create without attention to the market, and be cognisant of the inaccessibility of their language to the wider public. These all warrant further discussion.

Not long ago, I wrote asking when would artists be given the space to talk and be listened to. Well, I saw the Reimagining Borders event as such a space, albeit temporary. While few of the sessions during the week-long series of public conversations focused on visual art and visual artists, a space was nonetheless created for us to talk, quite different from being talked/lectured to. Here, in a very fluid manner, visual artists talked about art and new directions were proposed. Unfortunately, the topic was broad and the time was limited. Nonetheless, perhaps the organisers saw the benefit of letting artists set the agenda in the space they created for us and how beneficial the journey was for those who listened with openness and abandon to their preconceived notions of how such a topic should be approached. Other visual artists contributing to the two-hour journey included members of the Guyana United Artists, the Roots and Culture Gallery, and the Guyana Women Artists’ Association alongside other creatives and lovers of visual art.

Akima McPherson is a multimedia artist, art historian, and educator.