Transformations (2012), the gesture was repeated. The GWAA secured me a room to have an exhibition of my work in what I conceived of as ‘a show within a show,’ although the two shows existed on entirely separate floors of the National Gallery of Art (NGA), Castellani House.

I was happy to be offered the space as my efforts to secure the same space years before had been met with no response from the highest official of the institution. Elated, I titled the exhibition ‘Walk with me – a show’. I intended to bring several of the ‘Walk with me’ works back to life to define a room with related and intersecting works.

As I was installing the work for the show, a colleague artist entered the room and, seeing me pasting printed text onto the wall, suggested the work would look better if I bordered the cardboard with colour. She had no idea of my intention for the space or what was printed on the cardboard sheets but she had suggestions. She did not ask about my intentions. She did not read any of the text. She glanced around slowly and decided on the way I should have gone. I probably said, okay so she would go away.

‘Walk with me – a show’ was meant to be a meditation space, a space for thinking through forms of violence against women and girls. I showed ‘Walk with me III’, which I was unable to show properly at the Guyana National Visual Art Competition and Exhibition (GNVACE) in 2014 because, after the opening event, the projector was removed (see last week’s article). I used the NGA’s projector again with the acting curator’s agreement but with no interference. Over the course of 17 minutes, a woman spoke of her failed marriage, offered advice to girls, and shared how she reconciled the losses of her early life. Her face was not shown but her gesticulating hands were. Seven unfired clay ovals were displayed on three clear perspex shelves alongside the film projection. Each oval carried scars but from the first to the last the profile of the scars changed – deepening, disappearing, reappearing, and giving way to new scars. Together the film and ovals spoke about the healing journey. As we heal our emotional scars, their profiles change and new and past scars may appear.

On opposite walls of the room, I also shared ‘Walk with me IV – Jasmine’s Story’, another true testimony of walking away from a relationship that was marred by physical violence. A fairy tale without the happy ending, On the wall opposite the film and ovals were displayed – ‘Walk with me VI – Overcoming’, a sculptural installation alongside ‘Moodscape Introspection VI’, a painting.

This painting when first shown at the GWAA Annual Exhibition in 2002, attracted the attention of three distinguished ladies who standing before it discussed whether I had painted a woman in hijab and, as they put it, “the silencing of Muslim women.” I had painted myself. Silenced and confined within an oppressive bubble. The painting was meant to reflect the discordance I felt between my idyllic upstate New York upbringing and reality in Guyana. There I felt no limits because of gender. Here limits abound. The sculptural work comprised three shelves stacked in a single column with figures in postures of overwhelm at the bottom and figures in postures of overcoming at the top.

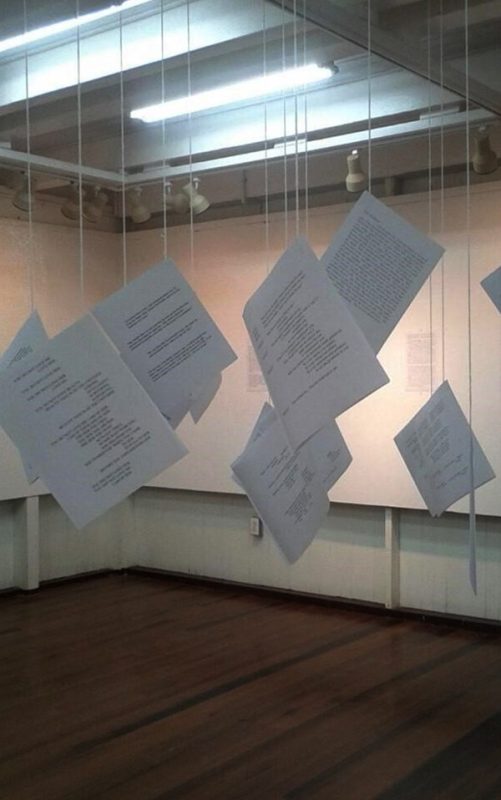

On a shelf between the figures and directly in line with the two sets of figures were biomorphic forms intending to stand for the trials and tribulations we each must overcome. In the centre of the room on standard printing pages words hung in space. They formed poems, letters and brief compositions. This work I titled, ‘Walk with me V – Text Suspended’. These were obviously the words of many individuals – women and children – asking questions, venting rage, begging for peace, and reaffirming self. These words hung in the silence of the room perforated by the voice of the woman in the film who spoke of her own journey to heal after her abusive relationship. The audio was set to play on a loop, a continuous audible presence in the midst of voices made inaudible by being words on paper, which may or may not be read, adding a layer of silence if not read.

Today, I wish I had spent more time in that room. But after installing the work I visited infrequently. I felt exposed. I felt drained. I felt vulnerable. Not only because the work differed so much from colleagues in our traditionalist local art context, but because the pain of my experience and those who I knew and embodied in making the work was not only visible but also palpable. The door to the show was kept closed as the portable air conditioner cooled the space.

(Perhaps that too offered sound. I don’t recall.) Opening the door and stepping in, however, I recall feeling like I was in a sacred space. The temperature of the room was cool. And the riot of sound and colour of the Guyana landscape beyond the walls were obliterated; the curtains to the window were closed. The walls were white punctuated by black text; oranges and blues on the painting; and the café-au-lait brown of the ovals and figures.

The voice on the audio spoke of healing. The hanging white sheets with printed text moved as the body moved and disturbed the air around it. Today the work exists in multiple places outside of memory. The film exists on a USB, the printed formats of Jasmine’s Story and Text Suspended are stacked in a folder in case I wish to use the sheets again, allowing additional imprints of life to these sheets already imprinted with a previous existence. Both also exist in a file on my external hard drive. The figures and the ovals are carefully wrapped and are in storage and the painting is displayed within my home.

‘Walk with me – a show’ no longer exists but can be reinstalled in a new space with the understanding that it will be a new work due to the inability to position each fragment in precisely the same way and the specificities of the new space offering new meanings to the work.

Akima McPherson is a multimedia artist, art historian, and educator