WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Tensions among some of the world’s leading economies have boiled up over a plan to raise new resources for the International Monetary Fund to contain the euro zone debt crisis, and a quest by emerging economies to win more say in the global lender.

World financial leaders gathering in Washington this week will focus on proposals for countries to contribute more money to the IMF so it is better prepared in case of fallout from any further escalation of Europe’s debt problems.

Emerging market countries like China, Brazil and Russia are willing to provide more money for the IMF, but they want something in return: greater voting power.

It has become a hot issue given negotiations formally began this week on the next phase of IMF voting reforms to be completed in 2013. The emerging-market push means Europe’s voting share will likely be further diluted.

In January, the IMF said it would need $600 billion in new resources to help “innocent bystanders” who might be affected by economic and financial spillovers from Europe.

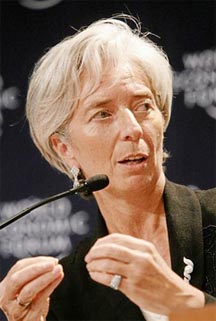

Earlier this week, IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said it might not need as much money as it had thought because economic risks had waned. On Friday, officials from the Group of 20 nations told Reuters the world’s major economies were likely to agree to provide the IMF with somewhere between $400 billion and $500 billion.

A G20 official said the fundraising effort would likely raise about $50 billion from Japan and a similar amount from China and Saudi Arabia, in addition to the $250-300 billion already committed by EU countries. Smaller amounts will likely come from countries such as Russia, Mexico and Brazil.

Budget politics

IMF funding will be discussed by the Group of Seven wealthy nations on April 19, jointly by the G20 and G7 that evening, and at a lunch the following day among the G20 and the Fund’s steering committee, G20 sources said.

Lagarde said she hoped to make progress on the issue at next week’s meetings but said an agreement could take time.

G20 sources said Beijing was being cautious given internal opposition to providing money for wealthy Euro-peans, even though the funds are meant to protect non-European nations.

Beijing, together with other emerging economies like Brazil and India, wants any funding commitment eventually tied to greater IMF voting power.

The United States, which is heading into a presidential election in which its hefty budget deficits are a key topic, has insisted it will not be part of the fundraising effort for the IMF. Canada is also unlikely to give money.

US officials say they are already helping Europe by providing swap lines to the European Central Bank to ease dollar-funding strains among European institutions.

Some senior IMF officials say that not having Washington’s participation had changed the dynamic of the fundraising effort since the United States is the largest IMF shareholder and its leadership is often sought on such issues.

IMF sources said an agreement on new IMF resources would likely be postponed until a G20 leaders’ summit in June.

“The Americans have to be part of this, perhaps not quite as much as they would’ve been in the past, but through some significant gesture,” said Uri Dadush, director of the International Economics Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “They have to be part of the leadership group that makes it happen.”

Growing frustrations

The growing frustration among emerging economies with the slow pace of IMF governance reforms has been exacerbated by a likely delay of a 2010 agreement on voting reforms, which the United States pushed for aggressively.

At the insistence of the United States, the reforms included changes in the make-up of the IMF’s 24-member board, in which two chairs occupied by European countries would go to emerging economies.

However, the package cannot go through until the US Congress approves the move, something that is highly unlikely ahead of November elections because it would require the authorization of additional funding for the IMF.

The 2010 reforms would move China into third place in the ranks of IMF voters and also increase the voting share of Brazil and India.

Paulo Nogueira Batista, the IMF executive director for Brazil and a constituency of other Latin American and Caribbean nations, said the United States needed to stick to its 2010 commitment.

“There is a commitment in the agreement to undertake best efforts to complete the steps by the annual meetings this year (in October), and that commitment includes the US,” said Nogueira Batista, speaking in his personal capacity. “I expect them to follow through with the commitment.”

“The problem is that the economic and political difficulties of the advanced economies, mainly the US and euro area, are having negative spillover effects on international governance,” he said, “They are negatively affecting the G20 and the functioning of the IMF through delays in the implementation of the agreed reforms.”

While there are frustrations with US delays, many countries understand the tough political environment the Obama administration faces.

The new negotiations under way on voting reforms will initially focus on a formula for calculating membership quotas. The new formula will influence how members’ voting shares are realigned to give emerging and developing countries more say.

Domenico Lombardi, a senior fellow at Washington’s Brookings Institution, said emerging economies were using the IMF’s push for more resources as leverage to gain even more voting power in the next round of reforms.

“This is a very political game,” said Lombardi, a former World Bank board director. “What emerging economies are saying is that even if the 2010 reform package is not approved, at least you have to be more lenient and concede more on the quota formula discussion.

“They are in a position to exert the greatest bargaining power they can and extract concessions from the advanced economies,” said Lombardi, who is also president of the Oxford Economic Policy Institute.