“Knives Out” does not start out centring its political themes, though. Rian Johnson (writer and director) has what at first seems a singular focus in “Knives Out”, as an unabashed successor to Agatha Christie’s ensemble type mysteries. In many ways this does hold up – especially its debt to her “Crooked House”. The bare-bones of the plot is that a famous mystery-novelist, Harlan Thrombey, has died. His throat has been slashed in what appears to be a suicide on the evening of his 85th birthday party. One week later, the open-and-shut case seems less so when police, and a legendary private detective (hired by a mystery client) arrive at his home to poke at the story revealing that despite appearances, the case is not what it appears to be. And everyone recently gathered at Harlan’s house for the party – family and staff – seem like potential suspects. Everyone, but for his distraught nurse and friend, Marta Cabrera, the only good person in this house. Astonishingly good. She is so good in fact that that merely telling a lie makes this noble woman projectile vomit.

The uncertainty of Marta’s heritage is meant to be a joke, but it’s unclear why we’re meant to be laughing. The film could be a deep incision of white, rich vacuity except the satirising here, like elsewhere in the film, is so uneven that the more it goes on, the more perplexing its intentions become. One can argue that a part of the film’s point is that every performance is riffing on a particular type. Jamie Lee Curtis as Harlan’s eldest is the snappish businesswoman; Toni Collette, as his daughter-in-law, is a pretentious wannabe-influencer; there is the SJW young woman (the film’s own descriptor of her); the Nazi teen, and so it goes. Types make up the whodunit, except, the film abandons its tropes early on and as its middle hour proposes itself as one shorn to Marta’s point-of-view it becomes cumulatively dizzying the way that the more time we spend with her, the less we learn about her beyond her saintly inclinations as a nurse.

In “Knives Out”, Marta’s place as an immigrant is not part of an earnest interest in her agency as an outsider in Trump’s America, but is instead a cudgel used to beat back the broadly painted evil of the Thrombey family. Sure, rich-white-generational families are prone to bigotry and racism. But, that’s hardly new. And “Knives Out” offers little beyond that revelation. The film can’t, or won’t, commit to saying anything beyond the purely superficial about rich people, and has nothing thoughtful to offer about race, immigration or displacement even when it’s shot in a way to emphasis it. Instead, it feels trapped in its own tonal ambivalence, unable to realise that the benevolent act that supports its twist only serves to further infantilise its heroine. Johnson’s plot is well designed, but nothing in the lensing or performances manage to elevate the material. We can see his good intentions, the ways he wants to present a benevolent act towards Marta as a righting of historical wrongs, trapping this social parable within a genre exercise. But he seems blind to the way this act, presenting Marta as the inevitable successor to the legacy of this family of gargoyles, is betrayed by its lack of interest in examining her own psychology, thereby rendering her voiceless in her own story.

“Queen & Slim” is, by design and necessity, much more conscious of its personal and political divide, centring the two immediately. This is not what makes the film more effective, though. In fact, “Queen & Slim” features a screenplay that (accidentally, at times, it seems) privileges the messy and discursive over the predisposed tightness of “Knives Out” which despite its limitations, is efficiently plotted. But, “Queen & Slim” is also challenging and risky in ways that betray its interest in people beyond ideas and concepts.

“Queen & Slim” too is riffing on tropes. The film is built with enough self-awareness that it evokes the Bonnie and Clyde myth, although that call-back is immediately ruptured by the idea of “if Bonnie and Clyde were black”. So, whereas the legend of Bonnie and Clyde that persists in art is one asking us to identify with the counter-culture celebration of vagabonds as a liberating aesthetic, “Queen & Slim” is about misery, rather than freedom, and about the weight of merely existing as a black person in America. The film opens on a very bad first-date. We do not learn their names until the film’s very end, and the words Queen or Slim (not their real names) are never uttered. She is closed off and caustic, he is apologetic and awkward. As he drives her home, a half-hearted proposition to go home with her foiled, and they are pulled over by a white police officer cruising for an argument. The already fraught mood explodes when she reaches for her phone and is shot in her leg and, after a scuffle the policeman lies on the road – shot by Slim in self-defence. And the two become yoked together by this tragedy, going on the run, piecing together a shoddy plan for survival over the next week of their lives.

Much of the film becomes a duet, where Queen & Slim learn to trust and understand each other – a love-story and road-drama that also becomes a road-trip movie. The road-trip element is baked into the film’s discursiveness – in truth plot is not the film’s keenest interest, nor its strong suit. The screenplay (from Lena Waithe, with a story by James Frey) is clearly struggling to marry the personal with the political and it’s immediately clear when the film teeters off-course with an ill-timed sex-sequence punctuated by cross-cuts to another scene (one of the few moments outside the protagonists’ perspectives) that feels immediately false and troublesome. Thankfully director Melina Matsoukas is there to rein it in. her astonishing control of the film’s own inherent restlessness is the force keeping this thing together, and it’s because Matsoukas with her love for potent imagery, her ability to make rote things like a reverse-shot compelling, emphasises her interest in empathy over everything else.

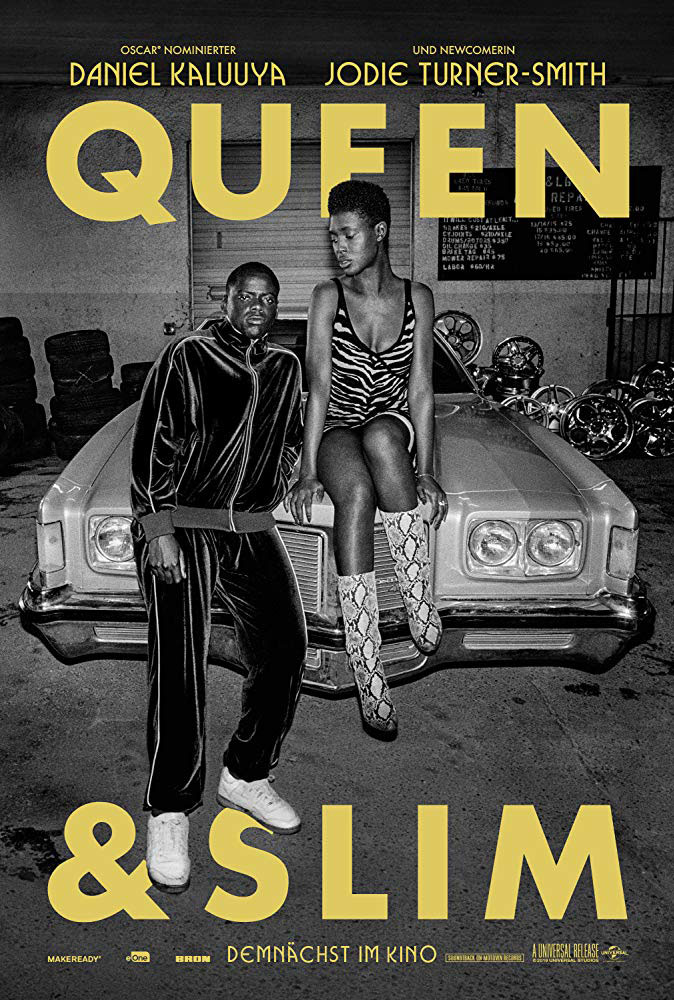

As the film goes on the dialogue between the two becomes less Very Important, but the film’s structure also becomes more frenetic. Still, even when her politics grow too ambivalent (the film is painfully leaden in two scenes with black police officers) the film is clear-eyed about its care for Queen & Slim as persons beyond their accidental film. On some levels, the script’s inclinations to pronounce them as figures of black mythology seem too heavy-handed. “You gave us something to believe in,” a black character tells them late in the film. It doesn’t need to tell us that, though. We can read it in the eyes of Daniel Kaluuya as Slim, in the sighs and grimaces of Jodie Turner Smith as Queen. Credit to the film, though, that it sees the pair as more than icons, but as real and tetchy people with inclinations beyond the concepts they represent. Even when the script struggles to marry real-world issues to humane drama, Matsouka’s direction (aided by some excellent photography, costuming and sound design) invites us in privileging clarity above obfuscation.

“Queen & Slim” doesn’t have the solution for how to marry its pop sensibilities with its real-world issues, either, but it’s confident and bracing more often than not. By the time it ends (the final shot of its character is a striking bit of biblical imagery) even its discursiveness feels more emblematic of its value than not. It’s vision, held up on the backs of Kaluuya and Turner-Smith, but most of all its director Melina Matsoukas, recognises how and why the personal is the political in 2019 America.

“Queen & Slim” is currently playing at all local theatres, while “Knives Out” is playing at Caribbean Cinemas and MovieTowne Guyana.