By Dr Baytoram Ramharack

[Against the Grain: Balram Singh Rai and the Politics of Guyana (2005) was written by Dr. Baytoram Ramharack]

It is safe to assume that Guyana will probably never again be graced by charismatically iconic figures like Balram Singh Rai, Cheddi Jagan or Walter Rodney. Much is known about Cheddi and Walter, less is known of Rai by a younger generation of Guyanese. This is partly due to the fact that Rai lived in self-imposed exile in London since 1970.

I “discovered” Rai while reading Cheddi’s political biography, The West on Trial. Cheddi had written favourably about him, but not nearly enough. Like Cheddi, Rai’s name was still frequently being talked about among my elders. From the little I knew then, I felt that the memory of Rai, like so many other Guyanese, deserved a seat at the table of history. Rampersaud Tiwari, a Buxtonian and cabinet secretary in Jagan’s government, arranged a meeting between Rai and myself. Rai had previously ignored similar requests – I surmised that he was probably deeply, and psychologically bruised from the bitter political experience he left behind. While I found him to be charming and humble, I was struck by the high level of formality he displayed. Rai introduced me to his wife, “Auntie Shanie” (Shankalli), the daughter of Johny and Siragia Hanoman from New Amsterdam, to whom he was wedded in June 1949. He referred to her as “my equal partner” who stood by his side in their life’s journey. He insisted there was no need for a biography of any sort – his political history was a matter of public record. I learned a lot about the legacy he left behind during the few days I “grounded” with him in his semi-detached home in Ealing, London.

Rai was born in Beterverwagting Village, a farming community established by Africans in 1838, the same year Indian girmitiyas (indentured Indians) first arrived in British Guiana (BG). Both of his parents were indentured to Plantation Lusignan. Radha, his mother, originally from Thana Bauthara, Lucknow district (Uttar Pradesh), arrived in BG in 1893 on the SS Elbe. Ramlachan, his father, who came to BG on the SS Forth, was recruited at the age of 20, on June 18, 1901 from the village of Majholia, Thana Chapra (Bihar). Rai’s father, instrumental in establishing the initial foundations of the Arya Samaj movement in BG, was the local village councillor and a part-time Hindi teacher.

Having been educated in a Hindu household, it was not surprising that religion played a pivotal role in Rai’s outlook in life. As a youngster, he emerged as President of the Beterverwagting/Triumph Arya Samaj. Much public hubbub was made, by some, of his deference to being a Hindu Rajput, as if it was a point of derision. Truth be told, the Emigration Pass of Rai’s father (#No 296/1053), issued by the BG Government Emigration Agency, listed his “caste” as a “Rajput”. Pandit Ramlall, another Arya Samajist and PPP loyalist from Corriverton, and who figured prominently in disrupting JP political meetings, explained that “Rai’s reference to being a Rajput …was an attempt to portray himself as a fighter, a warrior…he did not believe in caste distinctions”. Paul O’Hara, a journalist, recalled that “Rai may have had a touch of arrogance because of his ‘chhatri’ background.”

As an Arya Samajist, Rai drew inspiration from the reformist teachings of Swami Saraswati Dayananda. In one of his Deepavali messages, citing the activities of Dayananda, he confessed “it is my firm conviction that there can be no good government until statesmen and kings are imbued with religion and philosophy”. These words were a reflection of the enduring, and undeniable cultural influences upon his political inclinations. His long-time friend, Rampersaud Tiwari, remembered distinctly that Rai had delivered illuminating discourses on the teachings of the Vedas, Ramayana and Bhagavad Gita at community yagnas, hawans and pujas. As a Minister, he gave several addresses on the life of Rabindranath Tagore, Swami Dayanand and Mahatma Gandhi.

A question has been raised as to why Rai did not remain in Guyana and “beared the chafe”, opting, instead, to migrate to England with his wife and twin sons. The simple explanation was that he would have had to contend with the wrath of Forbes Burnham. In 1962, following Rai’s expulsion from the PPP, Burnham shared his opinion: “the minister’s [Rai] dismissal meant that the last vestige of intelligence was removed from the PPP”. It was an opportunity to recruit Rai with the hope of bolstering his [Burnham’s] Indian support in a desperate move to convince his American handlers that the PNC could garner multi-ethnic support in the crucial 1968 elections. In a letter to Bhaskar Sharma on May 14, 1996, Rai revealed that Burnham enticed him with several lucrative appointments: Queen’s Counsel, first Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, Ambassador/High Commissioner to any country of his choice, and Appeals Court Judge. Not wanting to be seen as a collaborator, he rejected them all.

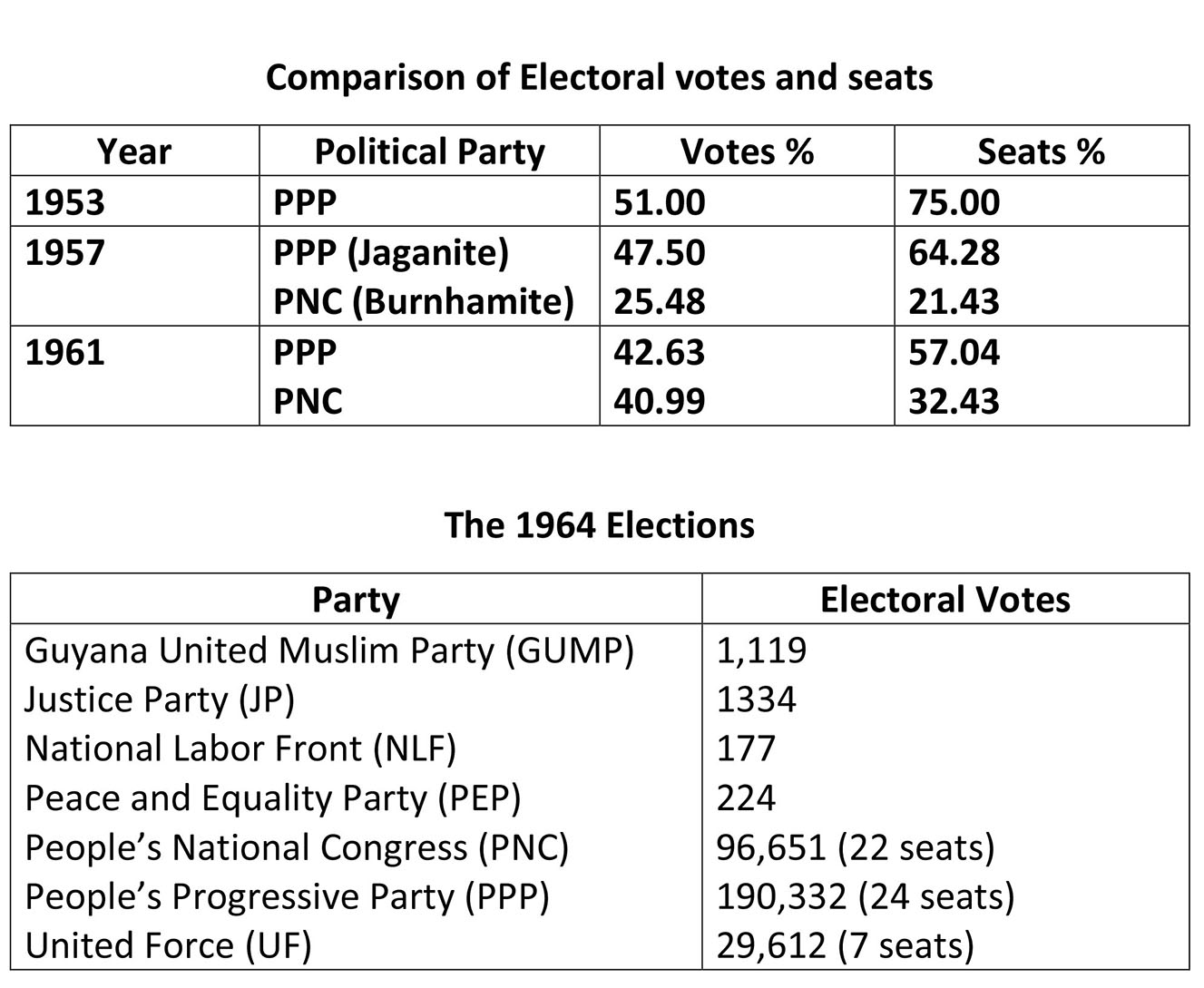

The other explanation has to do with the fact that Rai felt that Indians had rejected his leadership outrightly. The inability to capture enough votes (his party secured 1334 votes, less than 1%) in order to create an impact on the political landscape was a reflection of the failure of the Justice Party (JP), as much as it was equally a failure of Indians to heed his dire warnings. The 1964 electoral campaign demonstrated that Jagan’s charismatic appeal was paramount, and, compared to a nascent Indian-led party like the JP, the PPP was an impregnable force. The PPP argued that Rai was an “opportunist” and “Indian racist”, claiming that Bookers and the US had poured millions of dollars into his campaign and provided his party with electoral equipment. Rai, according to the PPP, was encouraged by Burnham to run for election so that he could “split the Indian vote”.

During the campaign, Rai warned Jagan’s supporters that Jagan would be denied political power because of his carte blanche support for Colonial Secretary Duncan Sandy’s imposition of a new Israeli-type list system of election based on proportional representation. Rai argued instead that in the interest of political harmony and social justice there should be a referendum to decide on the electoral system, and fresh elections should be held, followed by independence. The new PR electoral system meant that the PPP would not be guaranteed 51% of the votes it needed to be part of the government because Indians were outnumbered by the rest of the population “by about 23,000 – 25,000”, enough to give the combined opposition a majority over the PPP.

Rai’s argument was simple, and seemed logical. Given the racial configurations, Jagan’s Pro-Moscow Marxist ideology and external manipulations, Jagan and his supporters would be left out in the cold, EVEN IF ALL INDIANS voted for the PPP. Since the new coalition government would be formed by Burnham and D’Aguiar, and in an already ethnically divided society, Indians would have no meaningful representation in government. He identified two positions the JP would bargain for, both central to the welfare and security of Indians, should the JP secure substantial support from the Indian electorate: Home Affairs (with which he was already familiar) and Ministry of Agriculture (most Indians were rural/agricultural based). Rai, as well as Jainarine Singh, defended this position on the campaign trail, as well as in the party’s manifesto.

Rai’s argument, based upon the declining percentage of Indian votes, as well as the results of the 1964 elections was borne out by the evidence demonstrated below, which showed that Indian votes had declined from 51% to 42% between the elections of 1953 and 1961:

There is no denying that Rai was considered by the Kennedy/Johnson administration as an alternative to Jagan. The Americans were searching for a political solution during the Cold War to prevent the Pro-Soviet PPP from taking British Guiana to independence. Rai was critical of “the external alignments Jagan [was] forging” and the policies he threatened “to pursue under the guise of communism”. He argued that “Dr. Jagan and the PPP have alienated Western sentiment in favor of the Guianese people, all of whom, but particularly the Indian section of the community stand suspect of conspiring with International Communism, thereby posing as a security threat to the Western Hemisphere.” Given the vitriol and violence directed against Rai and the JP during the 1964 electoral campaign, the PPP successfully made a singular fact abundantly clear – To be Indian was to be PPP.

The conflict between Rai and Cheddi Jagan harks back to 1959 when Janet Jagan threatened to expel several top PPP members who supported Rai for Party Chairman. The events of the April 1962 elections for Party Chairman, which the Jagans were accused of rigging in favour of Brindley Benn, precluded any future possibility of reconciliation between the two most popular Indian leaders in the Colony. Rai’s expulsion from the PPP, and subsequent revocation of his appointment as Minister of Home Affairs on June 15, 1962 triggered a series of rebellions throughout the PPP base in the form of resolutions from support groups urging Jagan to retain Rai as Home Affairs Minister. As a foot note, Brindley Benn, Jagan’s choice for Party Chairman, would eventually leave the PPP in 1968 when the party was in opposition, formed the Maoist Working Peoples Vanguard Party (WPVP), was very critical of Dr. Jagan and the PPP, and his WPVP flirted with the WPA. Jagan later extended an olive branch to Benn, recruited him as a member of the “Civic”, gave him a seat in Parliament and later appointed him as High Commissioner to Canada. For Cheddi, communist loyalty goes a long way, even for comrades who defected from the party.

When the results of the elections were declared, Rai expressed confidence that the JP had exposed the Pro-Soviet/Marxist policies of the PPP. He regretted the fact that the JP did not win any seats “especially for the future security and stability of the country, but more especially for the Indians in the country”. He warned that “history will judge that the stand I took and the course I adopted were courageous and public-spirited” particularly in the attempt to “secure genuine representation for the Indian community whom Jagan was misrepresenting and misleading” (Chronicle, December 16, 1964).

Given historical hindsight, Rai was ahead of his time. He had foreseen the fact that Cheddi would be excluded from power and his largely Indian followers would feel the brunt of the Burnham dictatorship. The fact that the PPP is now fully in bed with the perfidious American imperialists, after 28 years of exile, is further indication that Jagan’s recklessness and Pro-Soviet Marxist ideology situated him on the wrong side of history.

There is a spirit of callousness embedded in the assumption that a person who migrates to a foreign country does not face new life challenges. It is a greater egregious impingement on social justice when pension is spitefully denied to someone who served his country honourably for 7 years. Between 2001-2006, ROAR Member of Parliament Ravi Dev attempted to have the PPP make a necessary legislative adjustment to allow Rai to collect his Parliamentary Pension. He was peremptorily rebuffed. Attorney General Anil Nandlall must be credited for working with Patricia Rodney to bring closure to the Walter Rodney affair. One can only hope that Nandlall, a “chhatri” who recently paid tribute to Rai, will be guided by the same benevolence to correct a grave historical injustice perpetrated against a former member of his own political party.