Missed opportunities

For some time now Guyana has been using the public-private partnership (PPP) to invest in the creation of several public goods. Proponents of the concept describe public-private partnerships as long-term contractual relationships between public and private entities to share the risk for the design, construction, and operation of infrastructure project or the delivery of services. The three things that stand out are risk-sharing, joint production and joint decision-making. As clear as that point of view is, the use of this development model in Guyana has triggered severe criticism. Risk-transfer from the public sector to the private sector, identified in a study published by the Commonwealth Secretariat as the key element in a public-private partnership, appears to be missing in several high-profile projects in Guyana. Analysts have identified this factor as a major weakness in such projects as the Berbice River Bridge, the Marriott Hotel project, the expansion of Guyana’s international airport and the stillborn Amaila Falls hydropower project. The lopsided application of this concept in Guyana has left the impression that public participation is often more anxious to proceed with action than private participation. Not only has this disposition led to accusations of incompetence, it has also led to missed opportunities for a wider application of the public-private partnership methodology.

Potential benefits

The rationale for using the public-private partnership model of development stems from several factors. The reason cited most often is the lack of funds by the public sector to carry out the many public works that are needed to keep the wheels of industry going and to meet the consumption and leisure demands of households. When governments alone have to undertake the public investment, it turns to taxpayers to raise money or to capital markets or bilateral and multilateral lenders to borrow the funds. Raising revenues to meet many deserving needs that compete with each other is not easy. Taxation means shifting money from potential private investment or consumption to pubic use and it encounters resistance when taxpayers feel overburdened and they cannot see the benefits to themselves. The alternative is to turn to the private capital markets where possible or to bilateral and multilateral donors. Donors too have financial and tolerance limits and they are not always ready or interested in funding projects that do not coincide with their national interests. Public-private partnerships give the private sector a chance to invest voluntarily in the project. The potential benefits from such participation from the standpoint of public finance are that they help to reduce initial capital costs to the government and reduce the need to operate budget deficits.

Very narrow

The tendency has been for the government to turn to the business community to join it in building the structures that it wants to build. The assumption is that the businesses have the money and expertise that the project needs and the public gains access to the resources through the PPP. This concept of the relationship appears to be very narrow, and as the case of the Amaila Falls showed, it is not always true. Under this scenario, households are seen as the public and are represented by the government while the private sector is seen as businesses which represent their own interests. That is a legitimate way to consider the PPP relationship. But, it ought not to be the only way of conceiving of it. Households too are part of the private sector and there is evidence that they can make a difference when used in a public-private partnership arrangement. They own factors of production such as labour and properties used for offices and factories. They own small and medium-sized businesses.

Big impact

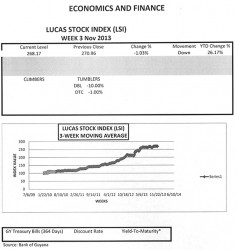

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) fell 1.03 percent in trading during the third week of November 2013. Trading involved five companies in the LSI with a total of 210,208 shares in the index changing hands this week. There were no Climbers and two Tumblers. The stocks of the other three companies remained unchanged. The Tumblers were Demerara Bank Limited (DBL) which fell 10 percent on the sale of 206,880 shares and Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) which fell 1 percent on the sale of 278 shares. Banks DIH (DIH) with a sale of 1,850 shares, Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) with a sale of 1,000 shares and Republic Bank Limited (RBL) with a sale of 200 shares remained unchanged.

As small as their individual resources might be, households could have a big impact on the delivery of services needed by the general public. The small-scale purchasing power of households when multiplied by the hundreds of thousands of citizens could amount to substantial resources. Evidence of this type of impact is seen in environmental projects in Kenya and India. A few years ago, Kenya was able to install lights in slums, streets and parks through a partnership that included low-income households. The programme resulted in the installation of 3,000 streetlights, including 33 high mast lights, along 50 streets serving over 150,000 households. Focusing on a different issue, the city of Pune in the Indian state of Maharashtra formed a partnership with rag pickers or as some prefer, green soldiers, to help clean the city. In one report on this story, it was noted that workers had been issued uniforms and safety-wear by the city, and they were going door to door collecting both dry and wet waste for a fee.

Creation of debt

The unwillingness to see households as part of the private sector might be causing Guyana to miss some great opportunities for speeding up its development. The Amaila Falls project is a perfect example of such a missed opportunity. A critical aspect of that project was the way in which it was being funded. Most of the money was coming from the creation of debt. Debt accounted for 75 per cent of the financing while equity accounted for 25 per cent. The debt was being guaranteed by the government during a period in which it would not have owned the asset. As far as the World Bank was concerned the value of the guarantee was part of the public debt.

According to data provided by Sithe Global, under the funding mechanism an estimated US$213 would have been spent on interest, contingencies, insurance for political risk, and advisory fees. These planned expenditures helped to push the cost of the project to US$858 million. These expenses were based on the financial arrangements that were in place for the project. It is conceivable that the project could have cost far less if a slightly different approach to the PPP arrangement had been utilized. In addition to the government raising its own equity stake in the project, businesses and households could have been offered shares through the capital market in Guyana to help bring the cost of the project down.

Becoming a reality

Questions remain as to how the cost of the project rose from US$350 to US$858 so fast. Yet, it is conceivable that an appeal to Guyanese to invest in the project could have borne fruit. An investment between US$200 to US$300 million most likely would have attracted support from Guyanese at home and abroad, thereby giving the project a shot at becoming a reality. Such an approach to the investment could have come with the additional benefit of knowing that Guyanese were vested in the project through their ownership stake. With much attention and incentive being given to others, many Guyanese feel detached and alienated from the public investment in the country. Those feelings of detachment and alienation that many have about public investment could have subsided or even disappeared.

Worth a shot

Given the importance attached to acquiring a cheap source of energy, it was worth a shot. The administration needed to pull out all the stops to get hydropower going in Guyana. The added advantage of encouraging a broad participatory approach to such large-scale public investments was that it could have reduced the outside influence and control over the project. The cost of doing business could have been lower not only by reducing the amount borrowed but also by putting pressure on the lenders to offer better interest rates. The confirmation of political support that Sithe Global was seeking would have been a moot point since investments of households would have been clear evidence that the project was being backed by the people of Guyana. It might not be possible to obtain the broad participation of households in such costly projects all the time but at least it could be done when possible, and where very critical investments are needed.

New projects will emerge where wider private sector participation could be sought. A new and perhaps different bridge is needed across the Demerara River and partially financing it through the use of the capital market in Guyana should be explored. A road that connects the East Coast of Demerara with the East Bank of Demerara is sorely needed. This project too could be a candidate for the public-private-partnership model using the domestic capital market. Such a move would have the added benefit of increasing the familiarity of Guyanese with the local stock market.