A 2010 McKinsey follow-up study, ‘How the world’s most improved school systems keep getting better’ made the obvious but yet noteworthy point that improvements in the education system are possible from any level of development. It also concluded that, ‘The school systems examined in this report show that the improvement journey can never be over. … systems must keep expending energy in order to continue to move forward: without doing so, the system can fall back, and thereby threaten our children’s well-being.’

In Guyana too, every strategic plan that has been consistently delivered since about 1990, together with the many reputable international interventions, have attempted to incorporate new knowledge into the education system. But whether or not the system has improved is highly contested in a quite intuitive manner.

For example one comment, lamenting the poor state of the present education sector claimed that from, ‘…a reliable source from the Ministry of Education in Guyana, 75 per cent of all the public secondary schools are underperforming. Correspondingly, only 25 per cent of all post-primary schools in Guyana are producing graduates capable of passing five or more subjects at the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CXC) level’ (The Minister is hiding the high failure rate in the public schools. SN 18/8/14).

If one were to ask with what is the information in the above statement to be compared with, its limitations immediately become discernible. Are we comparing it with our so-called halcyon days of the 1950s and 1960s or with the level of funding going to the sector? If the former, consider the following and weep!

In about 1962 the PPP government invited UNESCO to do a comprehensive survey of the education system and perhaps the present regime should again consider something of that sort.

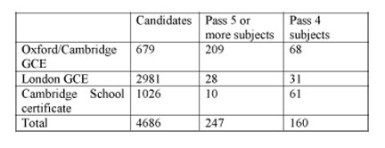

Examination results 1961

‘The significant fact is that the schools system in 1961 provided at most 247 candidates with the minimum qualification for entry to the University of Guyana. If we add those with passes in 4 subjects, then we have a total of 507 for the university, pre-service teacher-training, for the 6th forms and for commerce, industry and the public service’ (The UNESCO Educational Survey Mission to British Guyana. Government Printery, Georgetown, 1963). Compared to today, this is more like 5% passing with 5 or more subjects at the secondary level.

At the primary level things were not much better. ‘The quality of education provided in the schools is generally speaking poor, standards much too low to allow for the complacency in permitting continuation of conditions which force standards down and will force them down further. … The danger lies in the fact that many – teachers, heads, parents, supervisors, administrators – are coming to look upon these conditions as normal and consequentially tend to set their sights ever lower and lower’ (Ibid.).

In terms of funding, generally the quantity and quality of what one can expect from most efforts at social reform are heavily dependent upon the resources at one’s disposal. Although it is certainly true that if reform efforts are not rooted in good policy, expenditure could be wasted.

The McKinsey report gave multiple cases in which increased spending did not bear much fruit. As an example, after allowing for inflation, per capita spending on education in the United States increased by 73% between 1980 and 2005 and the student/teacher ratio decreased by 18%, so that by 2005, class sizes in the public sector were the smallest they had ever been. Barring some improvements in reading and mathematics of 9 year-olds, the levels of 13 and 17 year-olds in 2005 were the same as they were in 1980 (McKinsey, 2007).

In actual terms, Guyana has traditionally been spending less than its Caricom partners because (except for Haiti) it is the poorest of them. Although the relationship between actual spending and outcomes is not linear, there is usually an effect.

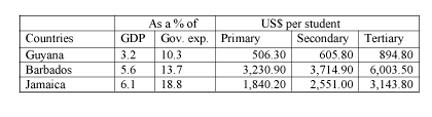

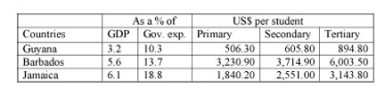

Education expenditure: 2012

UNESCO Institute for Statistics

Up to 2006, Guyana was spending about 5.1% of GDP (8.1% in 2005) on education. So perhaps the very low 3.2% reflects the so-called rebasing of the economy without any consequential changes being made to the sector budget. Noteworthy too is that tertiary spending was as high as US$1,700 in 2004 and has deteriorated ever since to as low as US$762.20 in 2011.

Partly as a result of this low expenditure, Guyana is also usually at the bottom of the table in terms of passes at CXC. For example, in 2014 pass rates in grades 1-3 for mathematics and English showed Jamaica (usually the weakest of the larger countries) with 56% and 66% respectively and Guyana 39% and 47%. Many of those who compare the public with the private sector in Guyana also tend to miss this relationship.

Another belief that is widespread in almost every education system that we had better note before we proceed is that there is a fundamental relationship between improvement of outcomes and class sizes. This has led to education systems employing more, badly paid and lower quality persons as teachers.

Yet according to the 2007 report, the available evidence suggests that, except at the very early grades, class size reduction does not have much impact on student outcomes. Of some 112 studies considered, 103 found either no significant relationship or a significant negative relationship.

Compared: a reduction in class size improved the performance of the average student only by about eight percent. But ‘the performance gap between students assigned three effective teachers in a row, and those assigned three ineffective teachers, was 49 percentile points.’

Even more alarming ‘ … all the evidence suggests that even in good systems, students that do not progress quickly during their first years at school, because they are not exposed to teachers of sufficient caliber, stand very little chance of recovering the lost years’ (McKinsey, 2007).