Malefactor (Left)

So you is God?

Den teck we down! Tiefin doan bad

like crucifyin!

wha do you, man?

Save all a wi from dyin!S

Malefactor (Right)

Doan bodder widdim, Master; him

Must die;

but when you Kingdom come, remember I.

when you sail across de sea,

O God of Judah, carry I wit dee.

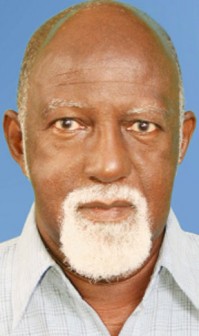

The most celebrated Easter poem in Caribbean literature is Mervyn Morris’ “On Holy Week”. It is a sequence of poems which when put together make up one dramatic piece; a dialogue theatrically presenting the dramatis personae of the Easter story. Like so many other great works inspired by Easter with its story of the crucifixion and resurrection, it is fairly faithful to the Christian plot but is not a religious message or statement. There is much more than that taking place in the poem thematically, dramatically, poetically, linguistically, politically, which reflect certain preoccupations of Morris and why he is an important writer.

Unlike so many poets, Morris is a very good reader of his work. He shares that particular quality with another colleague of his, Eddie Baugh, whose readings are theatrical performances. Morris has been often asked to read “On Holy Week” publicly and among the most acclaimed performances were his readings at the South Bank in London

Morris also explains that the sequence actually started with Pilate. When he started writing it he was an administrator (at UWI, Mona) and it occurred to him that Pilate had been misunderstood as the villain of the piece. “I thought many of the sermons I had heard were not fair to Pilate. He was trying to manoeuvre Jesus’ freedom”.

But some of the poems have appeared on their own in publication outside of the dramatic sequence, and indeed, can stand alone as individual poems. That is certainly the case of “Malefactor (Left)” and “Malefactor (Right)” which may be singled out as pieces that are characteristic of some of Morris’ wider preoccupations and his importance as a literary figure.

Morris’ other collections of poetry are The Pond, Shadow Boxing, Examination Centre and I Been There, Sort of: New and Selected Poems. The blurb on the latest collection by Carcanet Press (2006) manages to sum him up quite succinctly as “one of the most distinctive West Indian poets, his work characterised by economy, wit and humane seriousness. He makes elegant use of Jamaica’s linguistic range . . .” but he goes further than that in the way he uses language as a crucial part of his dramatization, characterisation and artistic statement.

Morris may be credited with making a definitive impact on the rise of oral quality, creole verse, and performance poetry in West Indian literature as a critic with his prize-winning essay “On Reading Louise Bennett Seriously”, followed by his editing of Bennett’s collections (Rex Nettleford also played a part in this area with Jamaica Labrish). As a poet he added his several consistent performances reading his work with an oral quality and uses of linguistic varieties at various “yard” venues and events at the time when dub poetry was being created and not only the Creole language, but Dread Talk was gaining ascendancy and beginning to be taken seriously in West Indian literature and its criticism.

It must be emphasized that the elements being treated here are not all that make Morris important, since they do not touch many aspects of his verse in Standard English, but they are certainly significant factors in his contribution to the literature. They accentuate his frugality with language as well as the dramatic quality. The Malefactor (Left) does not really believe, he is skeptical, while at the same time (selfishly) hoping Jesus can rescue him. He is unrepentant and is actually challenging Jesus to prove himself. He is the roots man on the political left, with his accusation of the system “tiefin doan bad like crucifyin!” Yet his last line “save all a wi from dyin!” is an ironic expression of Christian faith. The thief on the left does not realise that the crucifixion is an act to save all mankind from dying. But that is in a profound way, well above the superficial consciousness of the felon. Unknown to him, Jesus is really doing the very thing that he is challenging him to do to prove that he “is God”.

The Malefactor (Right) believes and seems to have already accepted Christ as saviour. He is on the political right in his conventional conservatism of acceptance. He apologises for the behaviour of his colleague on the left. He is a dramatisation of both the convert and the Rastafari image, which comes over in both his language and his references. Morris creates him in the persona of the Rasta man of previous generations whose chant was “peace and love, brotherman”. His acceptance that Christ can save him is expressed in the language of repatriation in which salvation for the Rasta is “sailing across the sea” back to Ethiopia. “Carry I wit dee” is also Dread talk.

Valley Prince

(for Don D)

Me one, way out in the crowd

I blow the sounds, the pain,

but not a soul

would come inside my world

or tell me how it true.

I love a melancholy baby,

Sweet, with fire in her belly;

and like a spite

the woman turn a whore.

Cool and smooth around the beat

she wake the note inside me

and I blow me mind.

Inside here, me one

in the crowd again,

and plenty people

want me blow it straight.

But straight is not the way; my world

don’ go so; that is a lie.

Oonu gimme back me trombone, man:

is time to blow me mind.

The other poem Valley Prince is not a part of the Holy Week sequence, but it illustrates associated qualities of Morris as a poet. It is about the legendary Don Drummond, one of Jamaica’s most respected trombonists who was a major player in the rise popular music from ska to rock steady in the 1960s. Apart from being revered as the greatest with a popular, even cult following, he was also acknowledged for his depth and the meaningful seriousness of his music. These elements particularly appeal to Morris in this poem in the way Drummond is popular, always surrounded by a crowd of adoring fans, but profoundly alone in the way they never understood him.

This comes out in his story which is alluded to in the poem. Apart from recording some of the best of Jamaican music and accompanying all the best singers of his time, Drummond played in clubs, famously at Bournmouth in East Kingston. He had a relationship with a belly dancer (probably also a stripper or “go-go dancer”) whose lifestyle could have driven him to jealousy. Moreso, not uncharacteristic of genius, Drummond was mentally unstable and in a fit, killed her. He was confined to the mental asylum at Belle Vue, which all Jamaicans are convinced, will “mad yu” rather than cure you.

In true Morris style (though not with his characteristic trade-mark brevity) the poem dramatises that story and captures the loneliness of Drummond’s radical depth and hurt. It is the personal agony that comes out in his music and that moved another Jamaican poet Anthony McNeill, to write to Drummond with a plea “may I learn the shape of that hurt . . .” Morris dramatises it in Valley Prince which thrives on contrasts, similar to those contradictions in the musician’s life.