Directly Involved

The value-added tax or VAT as it is more frequently called was introduced in Guyana in the year 2007 to replace the Consumption and other taxes which, ironically, were not consciously paid by the consumers. This tax burden or at least part of it was eventually shifted to the customers through the prices that distributors and importers charged. Despite reaching the consumer through the market mechanism, the obligation for paying the Consumption Tax was never obvious to the customer. On the other hand, with VAT, the consumer is directly involved in the transaction and the buck stops with the customer. Theoretically, there is no incentive for participants in the system to cheat since registration of the businesses brings them in the sight of the tax authorities who ostensibly can make checks to determine if they were cheating on VAT collections and submissions.

Discussing VAT is a very touchy and provincial subject for the tax authorities in Guyana, irrespective of whether the issue is about enforcing the law or justification for having the law.

There is often the belief that the motive is to malign its work. But, discussing VAT or any other tax for that matter in its administrative or operational context ought not to produce the often confrontational responses that emanate from the Guyana Revenue Authority (GRA). These matters are of as much interest to the general public as they are to those who are charged with enforcing the law. There are very few in Guyana who would disagree that VAT has revenue value to the country, even though they might disagree over the size of the tax.

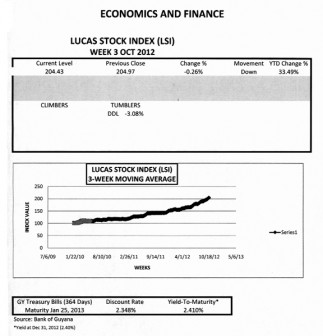

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) recorded a marginal decline of 0.26 percent in the third week of trading. The stocks of four companies, Banks DIH (DIH), Demerara Bank Limited (DBL), Republic Bank Limited (RBL) and Sterling Products Limited (SPL) remained unchanged from last week. The stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) recorded a decline of 3.08 percent, causing the marginal drop in the index. Notwithstanding the negative change, the LSI remains above the yield of the 364-day Treasury Bills by over 31 percentage points.

As hard the GRA might be working to achieve compliance, there might be evidence to suggest that VAT is not achieving two of its most important goals. One is VAT might not be resulting in a decline in fraud and tax evasion as articulated at the time of its introduction. Two, VAT might not be controlling the growth of overall consumption as was expected. These two assertions will be discussed in this article. However, because of space limitations, the article will be presented in two parts. This first part will essentially focus on the issue of tax evasion.

It is always troublesome discussing in a newspaper article issues that involve explaining numeric data, details of their construction and going back and forth between comparative sources. In doing so, one risks losing the interest of the casual reader of such matters as being addressed herein.

The default course of action is to simplify the arguments as much as possible as is attempted here. However, when such readers realize in the end that this article could also be about revenues for a cleaner Georgetown, a better drained city, better control of flies and mosquitoes, and safer roads, they might remain interested.

Evidence

The evidence for the two assertions about tax evasion and over consumption comes from a comparison between the effects of the Consumption Tax and the VAT on revenue collection and the growth in expenditure. This is a narrow inquiry into the issue and more detailed research would be needed to draw firm conclusions about the assertions made above for two reasons.

One, comparing the effects of the VAT to the Consumption Tax on revenue and the growth of consumption is not a straightforward exercise. It must be kept in mind that some items are exempt from the VAT while others are zero rated, thus causing the same neutral impact on revenue collection from the tax. Consequently, with the uneven application of the tax, the amount of revenue collected will not be equal to 16 percent of the value added at the end of the distribution process. The amount of money collected as a percent of total expenditure will be lower. Moreover, VAT has taken the place of several taxes, including the Consumption Tax.

Two, at the time of its existence, the Consumption Tax was applied to a narrow range of commodities, resulting in a tax base that was smaller and different from that of VAT. Moreover, the proportion of consumption that made up the taxable base was not fully known. In addition, the Consumption Tax carried different rates for different commodities. Further, the rebasing of the national accounts would have a greater impact on the tax base for VAT than would have been the case for the Consumption Tax. As such, matching up its revenue intake with the VAT has to keep those factors in mind as well.

Tax Evasion

Yet, it is possible to discern some characteristics that might be pointing to a serious bout of tax evasion. Alternatively, it could mean that too much of the retail trade is outside of the tax collection threshold. Official data taken from the Quarterly Report and Statistical Bulletin of the Bank of Guyana for December 2006 and March 2012 provide a basis for constructing comparative statistics on VAT and the Consumption Tax. It permits one to use a similar tax base, the value added for respective periods, to calculate the revenue effects of the two taxes. For the five-year period of 2002 to 2006, the proportion of the tax relative to consumption collected during that period averaged 14 percent per annum of the taxable base used. In contrast, from 2007 to 2011, the proportion of VAT collected averaged seven percent per annum of its taxable base. That represents about 43 percent of the potential income from VAT compared to between 56 to 70 percent for the Consumption Tax. From all indications, the Consumption Tax appears to have played its role in bringing in a higher proportion of revenue than is currently being achieved by the VAT.

The conclusion that can be reached from the information at hand is that 57 percent of potential VAT revenue is lost from the system. The smaller ratio of VAT to consumption is interesting because VAT replaced at least six taxes among which were the Purchase Tax, the Hotel Accommodation Tax, the Telephone Tax, the Service Tax, the Entertainment Tax and the Consumption Tax. Also, the VAT was applied to a base that was at least three times larger than the base on which Consumption Tax was collected, even as readers keep in mind that the research needs to be continued.

Revenue Leakage

Irrespective of whether one agrees with the size of the VAT or not, everyone should be concerned with the size of the likely revenue leakage. The administration had promised to undertake periodic reviews of the VAT system to ensure that it was meeting its objectives. It is not clear if reviews have been undertaken and the results are being kept for internal use alone. If any reviews have taken place, it is not known if any addressed the issues of fraud and tax evasion. To the general public, a possible 57 percent loss of revenue could not be coming exclusively from exemptions and zero-rated charges. Clearly, further research is needed to establish the likely impact that exemptions and zero-rated charges are having on the revenue leakage. A contributing factor could also be inefficient tax administration. But even if one estimates that as much as 40 percent of the loss was due to inefficiencies, exemptions and zero-rated charges, a likely annual loss of 33 percent of potential revenue from evasion is still a substantial amount of money.

(To be continued)