Introduction

Notwithstanding the caption of this article, the first part in last week’s Business Page dealt not with the Hand-in-Hand Trust Corporation Inc (HIHT/the company) but with Winston Brassington and his brother who Winston boasted had saved HIHT from the fate of Clico. I explained then that instead of using any speculative language with potentially adverse consequences to the company I would write the company for specific information and/or clarification on the company’s financial statements, the impact of its investment in Stanford Investment Bank, the directors’ efforts to rebuild the company’s capital base and its relationship with the Brassingtons.

Following receipt of my list of twenty-one questions, Mr Hewley Nelson, the company’s Managing Director and its finance officer visited me to give some explanations on the financial statements which are audited by Maurice Solomon & Co. Mr Nelson was as helpful as he could be, clarifying some of the disclosures in the financial statements and conceding that the notes to the financial statements could have been more explicit. I was told that persons “higher-up” would address me on the several other issues raised in my correspondence.

Jonathan Brassington

Let us start with the Brassingtons and the 2,250,000 shares issued to Jonathan Brassington in 2009. The general law and practice regarding the issue of new shares is to offer them first proportionately to existing shareholders so that the balance of control is unaffected by new issues. If this rule of pre-emptive right was followed, the offer of the shares would have had to be made to Hand-in-Hand Insurance group (90%) and NICIL (10%), leaving no place for Jonathan – or indeed anyone else – unless some shareholder(s) had passed up on the offer. To ascertain this, I asked the following questions:

Do the articles of Hand-in-Hand Trust Corporation Inc (Company) provide for pre-emptive rights on the issue of new shares?

How many shares were offered to the Hand-in-Hand group for the 2009 issue?

Was a prospectus or information package issued for the 2009 share issue? If yes, can I be provided with a copy?

How was the company informed that a Mr Jonathan Brassington might be interested in taking up shares in the company?

Was Mr Jonathan Brassington permitted to carry out a due diligence prior to his application and who carried this out on his behalf?

The company’s response – signed by someone who is certainly not among the higher-ups – that “All our shareholders were examined and approved by the Bank of Guyana” matches Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code for mystery, complexity and improbability. I consider it perfectly proper to conclude that the company is willing to conceal the details of its transaction with the Brassingtons which many find improper and unlawful. That does so little to help strengthen the company’s reputation for integrity when under pressure. Or indeed for that matter of the Bank of Guyana which had not previously distinguished itself in its supervision of Globe Trust and Clico.

Hoops of circumvention

Readers and the public have a much better memory and sense of integrity than they are often credited with. They will recall how Mr Keith Evelyn, group CEO of the Hand-in-Hand Group including HIHT, took the country through a series of meandering hoops of circumvention after the news broke about the company’s investment in Stanford Investment Bank (SIB). Here is the sequence to which I add my comments.

On February 21, 2009, Mr Evelyn confirmed that the Trust Corporation had investments in Stanford International Bank (SIB) but said that “they are not substantial … and efforts are being taken to safeguard against possible losses.”

Four days later President Jagdeo publicly revealed that HIHT’s exposure to the Stanford group amounted to $827 million (US$4 million) and another to $297 million (US$1.5 million) invested on behalf of pension funds. As CEO of the group Mr Evelyn’s description of the investment as “not substantial” cannot be dismissed as ignorance on his part. Even the understandable motive to prevent any run on HIHT, a deposit taking financial institution, ought not to justify the misrepresentation contained in Mr Evelyn’s February 21 statement.

At that point the quantum and impact had been set straight, or partially so, by Mr Jagdeo – who himself understated the significance of the loss to HIHT by an inappropriate reference to its total assets and his description of the institution as having a “capital adequacy ratio of 26.9 per cent as at the end of January 2009.” But clearly not straight enough for Mr Evelyn who one week later announced that even in the possibility only of HIHT losing its investment in Stanford, it would remain a stable and safe institution. Yet, in the same statement about HIHT’s strength, Mr Evelyn announced that the Hand-in-Hand Group of Companies had submitted for the Bank of Guyana’s approval a plan to “restore HIHT’s capital adequacy.”

Neither Mr Jagdeo nor Mr Evelyn has ever explained why it was necessary to restore something that was never less than strong, that was above the industry average and above statutory requirement. Characteristically, Mr Evelyn announced that since approval might “take any time between two weeks to three months” the restoration plan could not be released to the public. It actually took the Brassingtons’ deal to bring some sunlight to the whole episode.

Poor standards

Then finally, two days later, unable to hold the fort weakened by damning information available to the world but only belatedly acknowledged by HIHT, Mr Evelyn announced in Stabroek Business that the investment in Stanford was “a loss and we’ll have to record it as a loss, that is what any prudent institution would do.” Had the institution recognised the need for such prudence and transparency earlier, maybe we would have been spared the loss of more than US$5 million.

The institution has clearly recovered from the imminent dangers it faced post-Stanford. But it seems not to have overcome the institutional and national culture of secrecy and evasion so pervasive in the corporate world. Here was a unique opportunity for the directors, including Chartered Accountant Paul Chan-a-Sue, Dr Ian McDonald, banker Alan Parris, Charles Quintin and Mr Timothy Jonas of de Caires, Fitzpatrick & Karran to let Mr Evelyn and his management team know that the HIHT was moving on to higher ground – ground on which is imposed on directors a statutory fiduciary duty to act honestly and in good faith with a view to the best interest of the company and a general duty of care to others, including in this case depositors. That specifically with respect to financial institutions, there is a fit and proper test that directors should meet. Mr Evelyn’s conduct appears to have fallen below those standards and the directors should have long since confronted this issue. Instead, they follow his lead refusing to give direct answers to questions on matters of public and depositors’ interest.

With the silence of the Bank of Guyana and non-interest by the Financial Intelligence Unit (the anti-money laundering agency) or the Registrar of Companies which has the power under section 506 of the Companies Act to apply to the court for an investigation order in respect of the shareholding in any company, the matter of the Brassingtons would appear to be closed to the public. In the case of the Bank of Guyana, the HIHT’s directors claim that the company’s shareholders “were examined and approved” by the central bank.

The lesson from the Brassingtons

We are unlikely ever to know whether HIHT’s parent company refused to take up the new shares in HIHT, whether a prospectus or issue memorandum was issued by HIHT for the 2009 share issue, whether Brassington, Evelyn or other directors approached Jonathan Brassington, and who carried out the due diligence on Jonathan’s behalf before he undertook his only public investment in Guyana. Their answer also puts a lid on the identity of the two pension funds which lost some $297 million of their funds under HIHT’s management. No doubt no one will ever be held responsible.

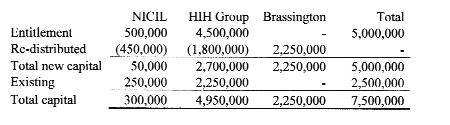

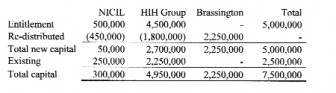

But before leaving the Brassingtons, just a brief comment on Winston’s claim that his brother rescued HIHT from a Clico-type collapse. The actual increase in the share capital was $500 million of which the Hand-in-Hand Group contributed $270 million, Jonathan Brassington $225 million and NICIL $5 million. This means that the HIHT group gave up a chance to take up $180 million of the new shares while NICIL gave up their right to take up $45 million – those shares were all taken up by Jonathan. Winston Brassington’s assertion that Jonathan saved HIHT can only be correct if no one else, including the HIHT group or NICIL was not prepared to take up any of those shares and if those shares were crucial to the restoration of the company’s capital base. That too we will never know, nor why the Bank of Guyana had not taken steps to suspend the licence of the company when the Stanford investment wiped out its capital base.

The number of shares available for take up by the shareholders, the amounts given up and the impact on capital is shown in the following table: Another issue about shares.

On August 24, 2011 the company had another share issue; this time in the form of 150 million preference shares approved by a resolution of the company to which are inscribed the signatures of Marcia Nadir-Sharma on behalf of NICIL and Winston Brassington on behalf of his brother. While these are only $1 shares, the proceeds did make the 2011 balance sheet look even stronger, adding another $150 million in stated capital.

While any concern about window-dressing could not be supported by available facts, the company’s failure to mention the redemption in a note to the 2011 financial statements as a post-balance sheet event, does not help the company. Indeed, that failure is compounded by another failure to make any reference to this 2011 share issue in the section Background on page 1 of the 2011 Annual Report which ends abruptly with the 2009 share issue.

The law requires that preference shares can only be redeemed out of a fresh issue of shares for the purpose of the redemption, or out of profits available for distribution. At December 31, 2011 the company had accumulated losses of $171M and there is no information that suggests that there was a fresh issue of shares to finance the redemption.

To be continued

Note: Ram & McRae acted as advisor to the Privatisation Unit on the privatisation of the GNCB Trust in 2002. The issues raised in this column all relate to events which took place at least seven years after that engagement came to an end, and are all matters in the public domain.