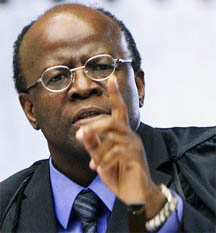

BRASILIA, (Reuters) – As the biggest corruption trial in Brazilian history comes to an end with convictions of once-powerful politicians, at least one hero has emerged from the mess — the first black member of the country’s Supreme Court.

People stop Justice Joaquim Barbosa in the street to thank him. Revelers in Rio de Janeiro have been buying Barbosa carnival masks and wearing them in demonstrations. His childhood picture recently graced the cover of the country’s biggest newsweekly with the caption “The Poor Boy Who Changed Brazil.”

The gratitude follows Barbosa’s dogged pursuit of guilty verdicts against some of the closest associates of former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva for their involvement in a widespread vote-buying scandal seven years ago.

A bricklayer’s son who worked as a cleaner and typesetter to pay his way through law school, Barbosa oversaw the landmark trial. The court last month convicted 25 people, including Lula’s former chief of staff, Jose Dirceu, for diverting at least $35 million in public money to bribe legislators to support his minority government after it took office in 2003.

In the first sentence, handed down last week, a businessman at the center of the bribery operation got 40 years in prison for money-laundering and fraud. Dirceu is expected to get jail time too.

The trial surprised a country where courts traditionally have let corrupt politicians get away with little more than a slap on the wrist. It also brought welcome recognition for a minority official in a country, Latin America’s biggest, where most top jobs are still held by whites even though half the population identifies itself as being black or of mixed descent.

For many Brazilians, the bribery convictions were proof that their country’s democratic institutions, while not perfect, have matured. The trial, they believe, marks a turning point in Brazil’s long history of corruption and impunity.

“There has been too much tolerance of notorious cases of corruption,” said Paulo Brossard, a former Supreme Court justice. “There was even a governor about whom people would say ‘he steals but he gets things done.’ I hope this case will bring an improvement in our public life.”

In sessions that riveted Brazil, Barbosa denounced the “mensalo,” or big monthly payments case, as an “an assault on public coffers” and accused Dirceu of being its mastermind. He seeks lengthy prison terms for those convicted of corruption, money-laundering and fraud.

The “trial of the century” – as Brazilian media have dubbed it – made Barbosa a household name. Some fans on social media networks are suggesting he run for president in 2014.

The 58-year-old judge dismisses all the attention as nonsense. He does, however, welcome discussions about race, discrimination and the lack of minority figures in other top jobs in Brazil.

Barbosa was appointed to the court by Lula in 2003 and will take over its rotating presidency later this month.

To get there, though, Barbosa had to battle racial barriers.

Discrimination, he said, “exists all over Brazil.”

“Nobody talks about it,” he told Reuters in a recent interview. “I do the opposite. I make it public.”

To many, then, it is fitting that a trial to clean up corruption is also prompting conversations about the court’s sole black justice and his much-admired handling of the case.

Barbosa has turned down the rotating presidency twice because of chronic lower back pain that forces him to argue cases standing up or reclining in an orthopedic chair.

Barbosa has a reputation for independent stances – he supports abortion rights, stem cell research and the transfer of slave labor cases to federal jurisdiction – and for engaging in heated exchanges with his fellow judges.

In an angry disagreement in 2009, Barbosa accused Justice Gilmar Mendes of undermining the credibility of Brazil’s judiciary and demanded respect for his views, while at the same time implying that his colleague from a rural state was guided by the feudal traditions of the past. “Your Excellency, when you address me you are not speaking to your capangas (hired hitmen) in Mato Grosso,” he said. The quarrel led the court to adjourn.

WORKERS’ PARTY

DENIAL

Lula, who remains Brazil’s most popular politician, was not charged in the bribery case. He has had a hard time, however, explaining what happened. When the scandal erupted in 2005, he apologized, but later denied the payments scheme ever existed.

That’s the ruling Workers’ Party line: the Supreme Court merely confirmed a guilty verdict reached months earlier by the Brazilian media.

“The so-called mensalo case is a political trial. The court has convicted people without proof,” said party lawmaker Carlos Zarattini, chairman of a special committee in the Chamber of Deputies that is pushing through an anti-bribery law for Brazilian companies.

Supporters of the Supreme Court’s role say its objectivity cannot be questioned since eight of its 11 members were appointed by Lula or his prot?g?, current President Dilma Rousseff.

The scandal has not hurt Rousseff, whose sky-high approval ratings are partly due to public perception that she has zero tolerance for corruption. In her first year in office, she fired six ministers facing corruption allegations.

DRAWING THE LINE

Polls show a vast majority of Brazilians approve of the Supreme Court’s performance in the bribery case.

A growing middle class in the world’s sixth largest economy has increased the number of educated and informed Brazilians who are not prepared to tolerate corrupt politicians.

Following the Oct. 9 conviction of Dirceu, anti-corruption demonstrators gathered outside the modernistic glass and marble Supreme Court building in Brasilia to send off balloons and chant: “Brazil has changed. The party is over!”

Impunity for white collar crimes in Brazil has reigned for decades. Fernando Collor de Mello, a former president who was impeached for corruption, returned to politics and now leads the Senate foreign relations committee.

According to Transparency International’s 2011 Global Corruption Barometer, 64 percent of respondents believed that corruption had increased in Brazil in the past three years, with political parties, the police and judges seen as the worst offenders, and the churches and the military as least corrupt.

Eliana Calmon, a recently retired federal judge, spent years rooting out corruption and abuse in Brazil’s courts, which are mistrusted by Brazilians and foreign investors alike.

Calmon, who famously called corrupt judges “toga-wearing bandits,” said the bribery trial overseen by Barbosa was a major step in establishing zero tolerance for corruption.

At the very least, experts say, the certainty of impunity has gone, making it riskier for politicians to steal.

Political consultant Andre Cesar believes Barbosa and the Supreme Court are drawing a line and telling Brazilians it is time to put an end to illegal slush funds in politics.

“The court is saying Brazilian society must change and Brazilians are beginning to see their judiciary in a new light.”