A national conversation having to do with child ill-treatment and ethnic discrimination broke out when an Amerindian child, dressed in normal traditional attire, was prevented from attending classes so garbed because it was thought that he was too exposed. Stabroek News’ editorial (30/05/2018) focused on the traumatisation of the child and one protester voiced well the anger of the parents of the child and the First People community: ‘I think it’s totally disrespectful to the Indigenous people of Guyana. That child is an example of who we are; he is a representation of the entire race of the First People of Guyana and I don’t think that they have been respectful to him and, therefore, they have not been respectful to this race because he represents our culture.’ The school rejected these positions, claimed that the entire issue was blown out of context and stated that in the absence of a national policy of the level of exposure allowable in schools it had devised its own standards, which are evenly applied. ‘We recognize that our first duty is to look after the best interest of the children we serve. We are particularly conscious of fostering social cohesion and encouraging children to be proud of their heritage, as well as learning of the different ethnicities that make us one Guyanese family, hence the willingness to host Culture Day.’

Since independence, a path has been set of our being liberal in trying to find the uniqueness of a Guyanese culture in the dress and landmark activities of all its people, and the Amerindians have contributed significantly to the national ethos, e.g. the Golden Arrow Head, Mashramani, the Cacique Crown, Timehri community and airport (now Cheddi Jagan) and the Umana Yana. The general outrage that the school’s action has caused is itself an indication of the existence of an unwritten understanding among all our peoples that ethnic groups should be allowed to express their uniqueness without undue restraint. Maybe there should be a written national policy on the level of exposure allowable in school, but Mae’s does not exist on Mars and thus in making its rules it should have been sufficiently cognisant of the expectations of its environment. Putting aside any untoward behaviour by the staff, over which there is controversy, it is difficult to deny that given the missive it sent to parents and the policy it devised, which was not properly communicated to parents, the school was responsible for the traumatisation of the child and an apology would be appropriate here.

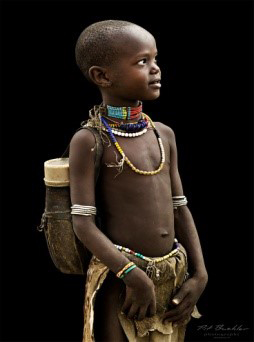

However, the specific question of whether the administration actually discriminated or intended to discriminate is quite another matter. If your answer to the question in paragraph one is yes – the African child in the photo would have been allowed to enter classes so dressed, then the action of the school in relation to the Amerindian child who was refused entrance in his traditional dress was discriminatory. If your answer is no – the African child would have been made to cover up, then the school did not discriminate against the Amerindian child or show disrespect for the Amerindian people. Or to put it another way, if the administration of the school acted similarly with the other ethnicities it would be wrong to accuse it of ethnic discrimination against the child and the First Peoples.

To answer my own question, particularly in the absence of evidence of a pattern of discriminatory behaviour towards Amerindians at the school, I will give the administration the benefit of the doubt and answer yes – it would have behaved similarly, because, from my cursory investigations, its culture of discipline focuses upon adherence to established rules, which on this occasion trumped cultural expression, the rules for which are at best rudimentary.

If the evidence does not support the position that the school intended to discriminate against Amerindians, what brought them and their organisations onto the streets claiming discrimination? I believe that, not without good reason, the root of the protest is to be found in the belief among the First Peoples that they are perennially and routinely subjected to a culture of disrespect at both the individual and institutional levels. For example, the letter ‘There is a need to enlighten children about indigenous culture’ (SN: 04/06/2018) made the former point, and on the same day as the Stabroek News editorial above, the Toshaos Council was complaining bitterly about the latter.

‘Silence is no longer the answer to the increasing level of disrespect that is being meted out to the Indigenous Peoples of Guyana. This public statement is only being made as a desperate effort to bring into the public the increasing level of discontent being felt by the Indigenous Peoples of Guyana. We have been trying since our meeting last year to have a follow-up meeting with His Excellency, President David Granger. Imagine the collective leadership of all the Indigenous Peoples of Guyana cannot get to see the President of Guyana. Instead we are sent from Ministry to Ministry to see other members of the cabinet, we have complied so far, but it seems to be a tactic to keep us from a meeting. It is our view that the Government has no intention or capacity for addressing the issues that affect the Indigenous Peoples of Guyana and because of this position His Excellency is unwilling to meet the Indigenous Leadership’. The council proceeded to threaten mass mobilisation if the rights of its constituency are not met. (President Granger still to meet with National Toshaos Council despite several promises. SN: 30/05/2015).

When, notwithstanding all the promises, sixty years after independence Amerindians remain by far the poorest in the land and are regularly treated in this manner, it is not surprising – indeed it is to be expected – that they will take umbrage at the mere hint of disrespect. The independent candidate, Mr. Michael Thomas, who was recently elected Toshao of Aishalton, has stated that the community needs to be politically united if it is to make substantial progress. While political unity integrates and magnifies collective effort, political power determines who gets what, when and how and thus the economic and social progress and the respect a people are shown.

Unfortunately, what Mr. Thomas observed in relation to Aishalton plagues the First Peoples community in general: in the existing national political status quo they are deliberately kept disunited. Thus, I conclude as I did in 2009: ‘if the indigenous people are within a reasonable time to share equitably in what Guyana has, they need to develop their specific political organisation and agenda and use their statistical weight to force its implementation’ (SN: 11/09/2009).