Peter W. Wickham (peter.w.wickham@gmail.com) is a political consultant and a director of Caribbean Development Research Services (CADRES). This organisation conducts political polls and research and has worked with all the major political parties within the OECS and across the Caribbean.

In the wake of the failed referenda on the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) in Grenada and Antigua and Barbuda, there are two important perspectives that need to be shared, relating to the reality of referenda and “truth” regarding objections that have been circulating. In advance of this conversation, however, it is important that I restate my commitment to regionalism and the development of Caribbean institutions which are an important component of the independence process. This process is admittedly frustrating but these institutions are still relatively new and conversations about infant institutions need to be seen as an important part of our evolution, which older states would also have encountered many years before us.

In Guyana, Barbados, Belize and more recently Dominica we have existed under the aegis of the Carib-bean Court of Justice for a decade, and notwithstanding former Barbadian Prime Minister Freundel Stuart’s recent threat to withdraw, it can generally be agreed that there is no widespread objection to the CCJ in any of the countries that have embraced its appellate jurisdiction. Indeed, if we are to take the outcome of the 2018 election in Barbados where a withdrawal from the CCJ was offered by the losing Democratic Labour Party as a referendum of sorts, it can easily be concluded that Barba-dians have soundly rejected the idea of leaving the CCJ.

This observation raises the logical question of why the CCJ has been accepted in these 4 countries but struggled to gain acceptance in St Vincent, Grenada (twice) and now Antigua, along with other islands where it has not been a priority. The difference is really very simple and revolves around the constitutional level of entrenchment that determines the ease with which the CCJ can be inserted. In some cases, a referendum is required, while in others a level of cooperation between government and opposition is demanded and has not been politically expedient. As such we have the CCJ in places where there is no referendum requirement and where political forces have found it expedient to cooperate.

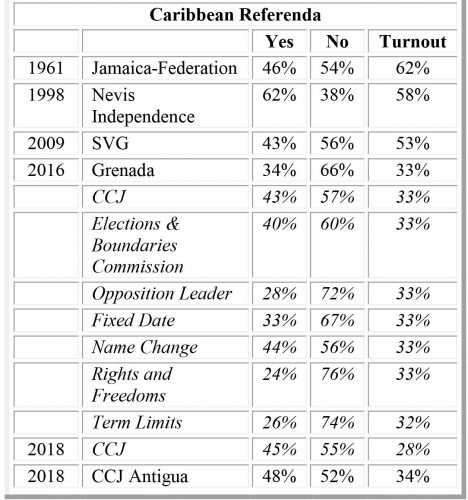

In places where the CCJ has been rejected or has not been attempted, it is perhaps not the CCJ which is “on trial” but rather that the CCJ has fallen victim to a political process that seems destined to fail. This is a fatalistic proposition that some optimists in the region have suggested can be countered with a strong educational campaign that seeks to inform and educate the masses about the wisdom of the move to the CCJ. A casual glance at the outcome of referenda, however, will demonstrate two important points. The first is reflected in the table which reflects these results and demonstrates that generally the turnout for referenda is appallingly low (38% on average). The second point is that the propositions almost invariably fail because the bar is set at 66.6% or two-thirds of those participating. The sole “success” in 1961 was the notable exception; however, those circumstances were entirely different to these now before us and at any rate the bar for success was 50%.

The low voter turnout speaks volumes about our interest in the issue and more importantly creates an avenue through which the process can be manipulated by those with a vested interest in its failure. Commen-tators have suggested that this level of apathy can be overcome by an educational campaign, but I would argue that history has demonstrated that the public has very little interest in these issues and while we can agree that they should, the fact is that they do not. Anecdotal evidence would confirm that the vast majority of us have not read our constitutions and most people who have come into contact with the Privy Council were convicted of murder and are appealing the death penalty, which is thankfully a slender minority of Caribbean people. This is equally the case in Barbados and Guyana; however, we managed to pass legislation facilitating the CCJ simply because there is no constitutional requirement to involve the public in such a decision.

The lack of interest in these issues creates an interesting political opportunity for opposition parties to flex their muscle and demonstrate their relevance in ways that they could otherwise not do. In both Antigua and Grenada, opposition parties retained 41% of the votes cast earlier this year and made little or no impact on the Parliamentary presence. These vanquished parties, however, now find themselves “needed” to encourage support for the referenda and it is not surprising they have seized upon this opportunity to highlight shortcomings of the government and to demonstrate what power they have. Certainly this will have little or no impact on the next election as the Grenada and St Vincent examples have proven; however last week opposition forces were able to claim victory for a brief period.

The challenge going forward, therefore, is to stimulate sufficient interest in the CCJ and other major constitutional issues among members of the public such that they would want to turn out to vote and do so overwhelmingly in favour of the proposition. It has been suggested that the solution is to take the issue to the people. However, it is challenging to speak to people about issues about which they are inherently disinterested, no matter how relevant, as the Grenada (2016) referendum demonstrated where a majority of people living in Carriacou voted against a name change that would have allowed their island to be reflected on their passports. Clearly this makes little sense but was rejected largely because people neither understood nor cared to understand.

The other aspect of the issue which is of interest are the apparently logical reasons why the CCJ should not be supported, and these have been articulated by Dr. Jacqui Quinn, a highly lettered daughter of the Caribbean. We can perhaps ignore the preamble to her statement indicating why she would be voting no in last week’s referendum on the CCJ in Antigua, which reads more like a curriculum vitae. We might also ignore the fact that Dr. Quinn was herself a Minister in the government that introduced the CCJ legislation into the Antiguan Parliament. Thereafter we can go to the key assertions she makes that the CCJ is open to influence from the leaders, is inadequately funded and is unsuitable because the CCJ is too familiar to our people. This last assertion is especially challenging as a rudimentary understanding of law suggests that in many instances, its application needs to be contextualized which places someone at a distance at a significant disadvantage.

With reference to the other concerns raised about the potential for political influence, it is glaringly obvious that these arguments are speculative since Dr. Quinn is yet to offer a single concrete example of such influence with reference to more than a decade of the CCJ’s existence to support her claim. To be sure, the smallness of the region is such that several of us are related by either blood or circumstance, but ironically this is no different from the Privy Counsellors, most of whom would have studied at Eton alongside the Royal family whose interest they have been asked to defend repeatedly. Such relations are a fact of life, but not ipso facto evidence of impropriety, and it is unfortunate that she was not challenged to provide evidence.

There are few who would deny that the point raised by Dr. Quinn about the lack of justice in the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) courts is worthy of merit (the argument she makes is that we must fix the lower courts before signing on to the CCJ); however, one struggles to understand what that has to do with the CCJ. It becomes even more ironic as the CCJ has just commented on initiatives which are designed to lend technical assistance to the lower courts in the OECS (to which it is not related), while the Privy Council is not known to have ever participated in a single initiative in the Caribbean other than to hand down judgments when asked. These efforts to mislead were also reflected in comments about the funding arrangements, claiming that eventually the CCJ “will be beholden fiscally to the politicians and governments,” a claim which completely ignored the robust Trust Fund which was deliberately designed to ensure the CCJ’s distance from any Caribbean government.

Sadly, these failures are likely to bring the conversations about the CCJ to a close for the time being and we can only hope that the leaders on both sides of the political divide in Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago have an epiphany and embrace the CCJ which could add some much required energy.