“What do you do with the mad you feel?”

It’s the question that Tom Hanks’ Fred Rogers asks the audience in “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood”. I’ve never been too attached to the real Mr Rogers, and yet that question, centred in the narrative of Marielle Heller’s empathetic film, seemed to reverberate backwards and forwards through so much of 2019 – cinematically, politically, culturally. It’s not new; that anger, that “mad,” has been the backbone of art for millennia. Yet, in compiling my favourite moments in film of the year, I kept thinking of how that mad we feel seemed central to so much of what filmmakers and characters were showing us this year.

There’s a moment in Greta Gerwig’s “Little Women” where Jo March, horrified at her reaction to a fight with her sister, turns to her mother (Marmee) for guidance. The beatific Marmee is so perfect, how could Jo possible learn to be more like her? “I’m angry every day, Jo,” she says. And like Jo, we are sceptical. She’s never shown it. Instead, she explains, she uses it to fuel her work, doing good to deal with the mad. It’s a worn missive in its way, but Gerwig respects these characters enough to treat the banalities of their lives with empathy and clarity.

Alfre Woodard, who I think gives the best performance of the year in “Clemency”, a film just outside my top 20, plays a death-row warden struggling to suppress the mad she feels until it overflows. And when it does, it’s thrilling and exhausting to watch. We understand it, vividly. So, in an assessment of the 20 films that feel most essential to me this year, I’ve been stirred thinking of how what their varying characters have done with the mad they feel.

“Jojo Rabbit” (USA: d. Taika Waititi)

“Les Misérables” (France: d. Ladj Ly)

Directors Waititi and Ly come to their subjects in different ways, but they’re both interrogating how children are scarred and exploited by the violent worlds they live in. In “Les Misérables,” Issa, a young boy in a Paris suburb, is the victim of police brutality that is accidental but traumatising. Issa would be exactly the kind of boy that Jojo, the Nazi-in-training who idolises Adolf Hitler in “Jojo Rabbit” is being fashioned to hate. And the hyper-realism of Ly’s film is a stark cry from the fantasy tinged satire of Waititi. Still, both films feel essential and profound in the ways they arrive at their central argument – we have to do better by children, if not we risk destroying the very best of what the world could offer.

“Honey Boy” (USA: d. Alma Har’el)

“The Personal History of David Copperfield” (UK: d. Armando Iannucci)

Iannucci’s tender and hilarious interpretation of Dickens is slated for a 2020 release, but I saw it at the Toronto International Film Festival and it feels remiss not to include it here. The film disregards fidelity of race, opting for a refreshing mix of ethnicities – with Dev Patel playing David as a young man who takes the anger from his childhood and turns it into art. It’s easy to miss the trauma of David when Iannucci sweeps us up in the comedy of the tale, but it’s the secret weapon of the film, where a boisterous laugh can exist in the same moment with a sharp realisation of how tragedy is unavoidable in life. It’s in the same vein that Shia LaBeouf exorcises his past in “Honey Boy”, writing a story based on his own chaotic childhood. As great as Lucas Hedges is playing the LaBeouf inspired Otis, a young-actor struggling with his addiction in 2005, the film is really about young Otis and his father, who LaBeouf plays. “Honey Boy” gazes starkly back at the trauma of childhood, and Har’el guides us throughout recognising that empathy is the only thing keeping us afloat in a chaotic world.

“Teen Spirit” (UK/USA: d. Max Minghella)

“Wild Rose” (UK: d. Tom Harper)

“Lina From Lima” (Chile/Argentina/Peru: d. María Paz González)

It’s the music that keeps the madness and sadness at bay in these inventive takes on contemporary musicals. Each of these films is carried on the backs of their lead performances – Elle Fanning Jessie Buckley and Magaly Solier are each turning in essential performances of the year. But, it’s instructive how the struggles of womanhood, whether a reticent teen, a Scottish girl yearning for fame, or a lonely immigrant Peruvian maid in Chile, inform the way that music becomes the one true way of escape. Of the three “Lina From Lima”, which is still seeking a proper theatrical and digital release, feels most essential and most damning of the ways that the contemporary world continues to fail those who need care the most.

“The Lighthouse” (USA/Canada: d. Robert Eggars)

“The Irishman” (USA: d. Martin Scorsese)

“Once Upon A Time in Hollywood” (USA: d. Quentin Tarantino)

If the previous trio of films saw women bathed in music, this trio sees men ensconced in their isolation – up to a point. Each filmmaker here is interrogating the age-old question of what it means to be a man and on an essential level, “The Lighthouse” sticks out. It’s profoundly silly and ridiculous. In fact, it’s so tied to the perspective of its main character it’s hard to be certain whether its absurd and absurdist myopia is a sign of character incisiveness of thematic ambivalence. But, it’s stylistic and formal rigour is astonishing. There’s a shot late in the film where Ephraim (an excellent Robert Pattinson) seems trapped by the camera. And I think of the way that moment runs through each film: a man alone. Whether in an abandoned lighthouse, a nursing home or a movie trailer, each of the men here is struggling (with varying results) to reach out to something, anything. Ultimately, it’s only Tarantino’s anxious Rick Dalton that gets anything close to a reprieve. Sometimes the mad that we feel goes nowhere, and we end up simply self-immolating.

#10 “Parasite” (South Korea: d. Bong Joon-ho)

Bong gets to the heart of class anger and subversion in “Parasite” taking the question of what to do with our unhappiness with the world. There’s so much at work in the film which deliberately lays out each moment like a puzzle to solve, but I keep coming back to Choi Woo-shik. He’s doing the film’s best work, and much of it because of the openness of his face turning in a performance teeming with emotion. The film is funny until it stretches the limits of humour and it becomes horrific. It’s a subversion of expectations and resolutions that represents the best and worst of what the world feels like sometimes – a capacity for hope, and a shrewd capacity for adaptation. But, also, a sharp realisation that the world is random, unfair and dangerous.

#9 “Synonyms” (France/Israel: d. Nadav Lapid)

How to try to explain the dizzying vicissitudes of this film’s weirdness? Do I even like it? Nadan Lapid’s frustrating, and frenetic film follows Yoav, Israeli immigrant in France trying to abandon his past and assimilate into French culture. But this synopsis, any synopsis, belies the tension running throughout the film. “Synonyms” is so chaotically keyed into Yaov’s perspective it misses any definition and yet its tale of immigration acclimation feels so profound and real and honest, I let out at a breath at the end of seeing it at TIFF I didn’t realise I was holding. It resists both your understanding and your embrace, even as it beguiles with its anger and chaos. I keep thinking about the end of the film and feeling a stirring of sadness in my gut. We never know what makes Yaov so angry but he carries all the mad of the world in him in a way that feels like a warning and that makes “Synonyms” feel essential – maybe love is the wrong word, but I feel tethered to it.

#8 “The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão” (Brazil: d. Karim Aïnouz)

If “Synonyms” renders its hero through his opacity, then “Invisible Life” is marked by its astonishing clarity. The emotions and feelings here are so true, that it becomes too much. This film overwhelms the senses in a way that becomes too much to bear by the end. Aïnouz’s film, feels like an essential work of the year for the way it glances back at the past to reveal so much about the present – about family, about love, about trauma but mostly about the way women struggle, and recuperate and carry on.

#7 “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” (USA: d. Marielle Heller)

# 6 “Little Women” (USA: d. Greta Gerwig)

Few films understand empathy as distinctly as these two. Lloyd Vogel is the bitter sceptic as is Jo March and it’s a feeling that we all might struggle too much with in 2019. In “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood” never takes these characters or their pain for granted. Instead, she invites us into their sadness, and their struggles in a way that is always thoughtful and never condescending. It’s shrewd take on a would-be biopic, and a sterling example of anger and pain can be healed.

And just as Heller plays with the biopic, Gerwig improves on “Lady Bird” by showing a shrewd understanding how adaptation can tear something apart while honouring it. Gerwig leans into the sadness of this story. The film can’t solve Jo’s scepticism and doesn’t care to. Instead, it recognises that human complexity demands we entertain conflicting emotions at once. So, “Little Women” – like Jo – frustrates while it charms, amuses while it lacerates, and reveals itself in unceasing sincerity.

#5 “Atlantics” (Senegal/France: d. Mati Diop)

The care that Diop has for the sensibility and fate of a young woman in many ways reveals some of the best of the possibilities 2019 can offer. There’s a restless postcolonial ambivalence at work here, a realism that means the supernatural, a keen feminist identity that also works as an economic critique. That this is Diop’s debut seems a marvel, every frame of this film seems assured but it’s also spontaneous and resistant to the idea of genre or rules. It’s thrilling and breath-taking work but like that final shot, it all comes back to that young woman – Diop’s love for faces, and the fate of these people is a reminder that films can see beyond the macro events of the world and embrace the micro-situations of humanity.

#4 “The Blonde One” (Argentina: d. Marco Berger)

So much about “The Blonde One” feels counterintuitive to its effect. It’s an especially limited viewpoint, there’s something quaint in the archaic way its “romance” develops, it takes pleasure in the banal and the mundane but it’s so well-modulated with a desperate anxiousness that recognises the inevitable unease that always half a step away from queer desire. Bodies are shot in isolation, a hand on a thigh, an out of focus torso, a hand by a hip and out of context it all seems rudimentary but the successive way that images become stories that become themes is intoxicating so that by the end “The Blonde One” feels almost too much to bear.

#3 “Ema” (Chile: d. Pablo Larraín)

I resisted putting Pablo Larraín’s film on this list, only because it’s bound to straddle the line between 2019 and 2020 releases. It’s enjoyed a handful of festival releases and a Chilean release this year and is likely to enjoy worldwide theatrical release in the North in 2020, but I’ll take any chance to sing the praises of what feels like the most uniquely specific and bizarre film I’ve seen this year – and that’s saying a lot. Any plot description seems foolish, instead “Ema” works best as an angsty mood, capping off the decade by showing us that there truly is nothing Pablo Larraín can’t do. He directs Ema as a love story, a tale of artistic tribulation and tale of parenthood all wrapped inside a reggaeton-infused fiery psycho-sexual thriller.

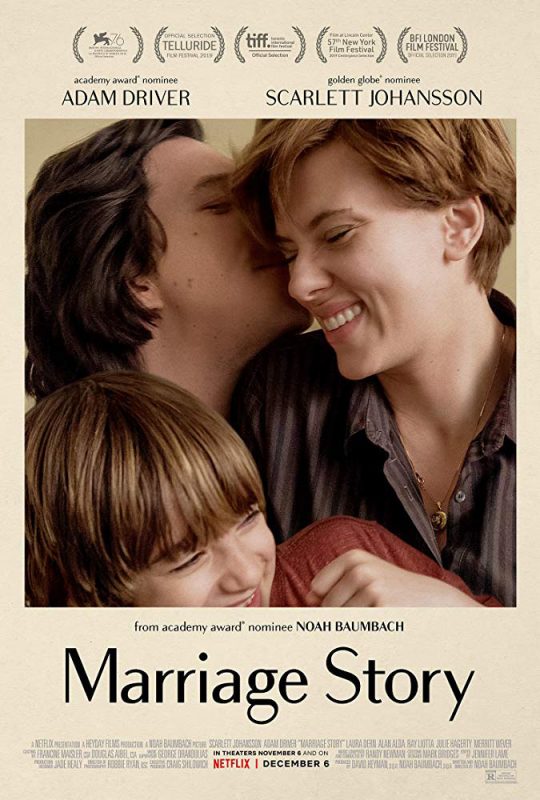

#2 “Marriage Story” (USA: d. Noah Baumbach)

#1 “Portrait of a Lady on Fire” (France: d. Céline Sciamma)

Up until I finished writing this, I wasn’t sure which of these was my #1, and by the time it’s published I may have changed my mind. In “Marriage Story”, a couple deals with divorce, while in “Portrait” a couple deals with love even as they must face imminent separation. The films are working in different registers. Baumbach is all about deliberation and planning out his sequences, Sciamma is languorous and impressionistic. But, the differences point to the gamut of wonders 2019 has offered to us. Performance and perception affect the tenor of the way the characters respond to each other and the way we respond to them. In “Portrait”, Marianne angrily smudges a completed painting after a critique from her lover, in “Marriage Story” Charlie funnels his real-world despair into a not-quite-impromptu rendition of a Stephen Sondheim song. Art intersects with life intersecting with anger, with sadness and with hope. The chord of the Vivaldi’s summer piece that closes “Portrait” feels like the soundtrack for 2019. That piece of music is preternaturally anxious, unsettled, unceasing. The way that Adèle Haenel’s face takes us on the journey Héloïse is experiencing listening to the music is the way I feel thinking about 2019 in cinema. It’s a lot to take in, but at it’s best it’s been unceasingly profound and wonderful.

The best of 2019 in film has taken the emotions of a world in crisis and turned them into beautiful film. Which is all we can hope for.