Last week, amidst the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, two French doctors appeared on television discussing the possibility of testing experimental treatments against the virus in Africa. They likened the proposed idea as analogous to treatments done on prostitutes for the AIDS virus. The moment, horrifying but not necessarily shocking, crystallised the reality of troubling race relations across Europe and the rest of the Global North – the ways that racism (and classism) were baked into everyday life. Into media, medicine, and culture. It was a familiar tale of racism as entrenched in cultural practices in the Global North.

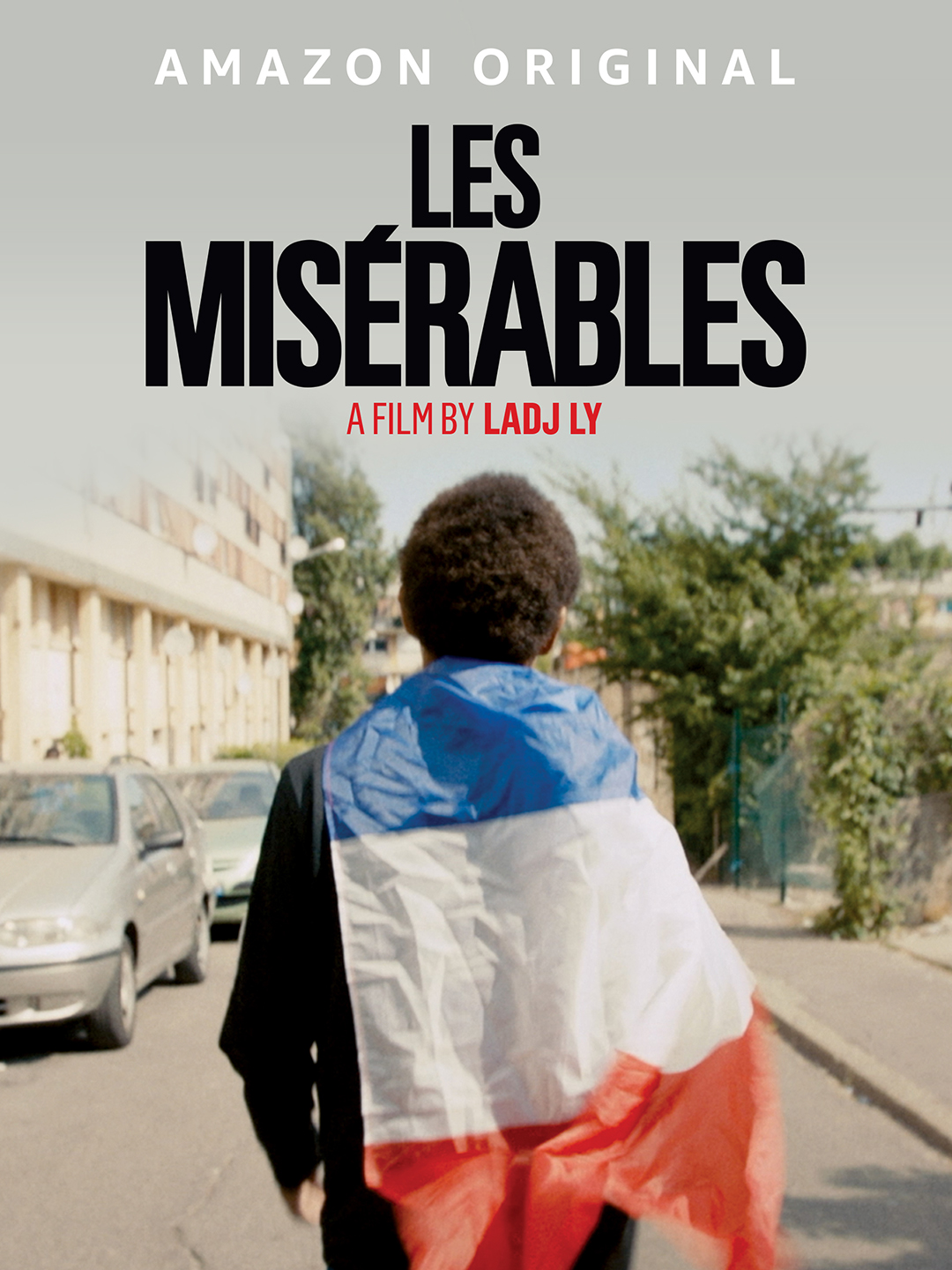

A few months earlier, at the César Awards (the top honours for French film), Ladj Ly’s “Les Misérables,” an examination of structural racism in a suburb 50 miles north of Paris, had emerged as the top winner that evening. “Les Misérables” won the hotly contested prize over critical favourites that seemed to be doing more aesthetically creative things with the film form and yet the moment only crystallised the interminable applicability of race relation as a theme in media.

2019 was a great year for international cinema, and two of the best of the year were from France. Since its premiere at last year’s Cannes ceremony, “Les Misérables” emerged as a contemporary film arguing for its relevance against Céline Sciamma’s tender lesbian-drama “Portrait of a Lady on Fire”. “Les Misérables” would go on to be France’s official submission for the Academy Awards’ Foreign Language film category, but lost to “Parasite” before winning in its home country at the César’s.

And, yet, there’s been a vague air of dismissiveness towards “Les Misérables” – seen as another “message” movie, another social parable that’s more about content than form. But, even as examinations of race have littered art over the centuries, the significance has not dwindled. And, indeed, Ladj Ly, who directs from a screenplay he cowrote with Giordano Gederlini and Alexis Manenti, is depending on the film’s script to carry a lot of its thematic heavy-lifting – this is a story that reflects familiar modes of power that show us a world we know all too well. But the ways that “Les Misérables” unsparingly commits to its conceits, thematically and aesthetically, make for a film that is bursting with restless energy and is immediately conscious of the 21st century zeitgeist in a way that feels profound.

“Les Misérables” tells its story in a brief 100 minutes, and it feels shorter than that. The urgency that’s pulsating through the film is endemic of that same restless energy that Ly is using to tap into a sense of angry despair that each character on screen seems to recognise. The film’s opening provides a bit of misdirection with an ostensible salve, that is all too temporary. A crowd of people, many races and ages, cheer as France attains victory at the 2018 FIFA World Cup, which provides a moment of unity between class, race and age. But celebration is passing. Real life lurks beneath. And in the city of Montfermeil, outside of Paris, that reality is dangerous.

Our initial entry point is new police-officer Stéphane Ruiz, who is assigned to an anti-crime brigade in the city and covers two of his colleagues on a walkaround of the neighbourhood. We quickly realise that his colleagues, one white and one black, abuse their power, thereby creating a tense relationship with the mostly black community. And an already uncertain situation becomes complicated as Stéphane’s story intersects with that of a stolen lion-cub from a circus, a young slum boy’s trenchant behaviour, a gang war that’s slowly percolating and tensions of race and generation that reach a catastrophic crescendo.

We know from the first shot of the three police driving around the city that things are destined for chaotic tragedy. It’s not so much foreshadowing as Ly expertly emphasising the foreboding sense of tragedy looming over everything. This is not quite Victor Hugo’s sprawling melodrama, but this is a fable with a clear purpose. How could it not be when it lifts so heavily from Hugo’s own “Les Misérables” (although it is not an adaptation of that text). Ladj Ly’s commitment to that kind of social realism creates a convulsion of complex developments, creating fissures of tension in the film’s development but serving as an essential recognition of his skill in his feature-length debut.

Even as Ly introduces Stéphane as the film’s first audience surrogate, the film is not beholden to his perspective or even particularly apologetic about the police. It is, instead, thoughtfully complicated in leaving us no answers on right or wrong. Instead, Ly leaves us with the germ of an idea – the film ends on a climactic moment followed by a quote from Hugo’s novel – leaving us to discern where our allegiance may lie. And it is credit to the sensitivity of the work here that the more natural “correct” answer feels as empathetic as the less natural and more complicated answer.

Ly’s empathy as a filmmaker moves beyond his screenplay, and manifests the look of the film. The televisual style of the film is not a lazy stand-in, but becomes Ly’s own way of committing to a hyperrealism that lays bare the worst (and occasionally, the best) of this contemporary world. Ly knows the people in the film, they are vivid and real in a way that make even the least charming of them feel like someone you may understand. What compels about “Les Misérables” is that the its central atmosphere is not modulated through anger. Or, even when it is angry it is also thoughtful and melancholy in a way that recognises the aching despair that feels endemic to lives that are damned before they are even developed.

As coronavirus reminds us of our own limitations (and strengths) as a society, it feels natural to think about the media we consume, what it tells us about ourselves and the world around us. In a year of so many excellent European films, “Les Misérables” is profound in its simplicity. These are not new or unfamiliar story, but it is a familiar version of a never-ending story that remains apt as ever. Structural inequalities will ruin us unless we rethink the ways our societies function.

Les Misérables is available on Amazon Prime Video