2002: Long Island, New York. Frank Tassone, a high-school superintendent, impeccably dressed in a fancy suit, preps for an evening assembly meeting with parents of Roslyn High School. The school board president (a wonderfully hapless Ray Romano as Bob Spicer) enthusiastically preps his entrance singing praises to Frank, and stroking the egos of the parents – SAT scores are up, college admissions are better. “Our children,” he all but croons, “are getting smarter.” Frank walks on stage to thunderous applause and atonal music that punctuates his big, but effortful, smile. We know before the film explicitly tells us that something is amiss. It’s not just the winking irony of the title which appears immediately after Frank’s million-dollar-smile. The two-minute sequence immediately prepares us for the film’s own dichotomy of superficial values with underlying rot. The next 106 minutes are less discerning.

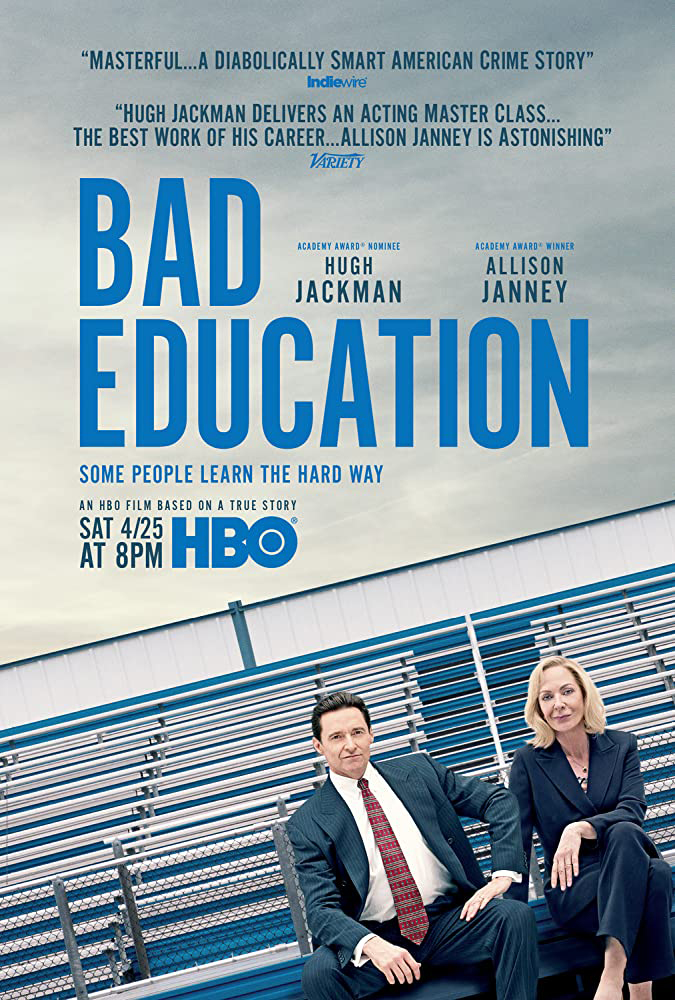

The source for “Bad Education”, directed by Cory Finley and written by Mike Makowsky, is a sixteen-year-old New York Magazine article about the largest public-school embezzlement in American history. It feels apt for our current times of economic malfeasance. Frank Tassone is a surface level charmer, hiding his occasionally sociopathic inclinations and avarice behind well-coifed hair, and an immaculately created personality. His assistant, Pam Gluckley, is his partner-in-crime but things go awry when Pam’s own embezzlement is revealed and Roslyn High School must manage the fall-out of a scandal that uncovers the falsity of surface level niceties.

But “Bad Education” never lives up to its almost painfully relevant potential. In part, the film’s own atonality seems to besiege it with issues. Part-satire, part-thriller, part-comedy (albeit very noncommittally), part drama – the parts of “Bad Education” coalesce to a film that feels wholly ambivalent about itself. In a recent Variety interview, Hugh Jackman admitted some initial trepidation at playing the role of Frank because of his own inability to work out the tone of the script. “It felt like three genres in one,” he confesses. And he’s not incorrect. Although it’s a problem that his performance is least affected by. Jackman is the strongest asset in “Bad Education”, charming in an effortful but also earnest way, making him normal in his vanity rather than monstrous or even anomalous. But even as he marries the film’s own inconsistencies about Frank’s transgressions, “Bad Education” does not seem as astute on what it’s trying to show the `audience. Its most distinct moments seem intent on playing satire, but Finley and Makowsky seem uncertain as to who or what it is that they’re truly satirising.

In some ways the film’s own ambivalence, towards Frank – and then later self-reflexively towards itself – feels apt. Except the ambivalence seems better suited to a different version of this story that was less about uncovering a wrong and more about wallowing in the ordinary awfulness of all the adults in the film – with a few exceptions. But Finley can’t commit to that more unpleasant film and by the end that ambivalence makes this film seems uncommitted to really making establishing any clear perspective on the things it chooses to represent.

Instead, stirred by the initial but consistent atmosphere of unease the film is working its way towards inevitable revelations of impropriety, punctuated by a diligent high-school reporter, and it’s one of the film’s key areas of leadenness. Rachel Bhargava is the student journalist who unwittingly stumbles on to the story that will uncover a scandal and there’s a clear dramatic arc about tragedy and hubris that Makowsky creates by having Frank’s own careless deployment of charm be the moment that nudges her in the right (or wrong) direction. But, even as this investigation is integral to the film, it’s a plot-line that feels trite especially in an early scene where the beleaguered teenage editor-in-chief educates Rachel on the pointlessness of student journalism.

It’s an irony that the film, which sets itself up in the final coda to encourage us to question the surface-level goodness of the things around us, seems itself besieged by its own surface level attraction. The film is slickly produced but the central hollowness of its engagement with Frank feels rarely perceptive. The most perceptive technical aspect of it all is Michael Abels’ score which provides a jolt of clarity in the film’s opening, with a bombastic showmanship that immediately signals something amiss. It’s not enough to make the film feel truly insightful even as it offers an interesting counter to the more prosaic look of the film – there’s something interesting about the way it treats the early 2000s as a world of dun brown dullness but the film is rarely visually challenging, or even complex. Even as the film itself might precipitate retroactive interest in the real Frank and the bureaucracy of the education system in and out of America, it seems resistant to doing that.

The film’s idea of Frank’s vanity seems whittled down to a too prosaic account of a gay man hiding in plain sight. Although it appears torn on examining this, the most consistent arc is a brief one with an excellent Rafael Casal as a young dancer Frank has an affair with. But the film is committed to believing that these people are beyond understanding. So, it accounts for the depravity of the embezzlers in the tritest of ways. Moreover, the film never really engages with the complicity of parents, who are quick to point figures but benefit from Tassone’s sociopathy with children who seem coddled by their own privilege. For a film that rests on investigations, “Bad Education” feels decisively incurious throughout its running time and is instead content to present rather than analyse, which is not an inherent flaw but sits paradoxically with the way the film regards its own self.

And the lack of anything to really challenge you is, perhaps, what I find most frustrating about “Bad Education”. Sure, it’s based on a true story but “Bad Education” is so consistently unsurprising for a film that seems to depend on revealing depravity that should make us gasp, or at least make us think. There’s something intriguing in the ordinariness of the people that make up the film but the film itself feels more ordinary than perceptive.

“It’s only a puff piece if you allow it to be,” Frank tells Rachel in an early scene. It’s the bit of context that sets Rachel on her search and it’s also meant to be a sly indication that everything changes with context and focus. “Bad Education” is not without its pleasures but it’s more puff than perception. There’s little to hate here, but its few triumphs feel too little to recommend.

Bad Education is available to watch on HBO Go.