At the end of “The Mauritanian”, Kevin Macdonald’s legal drama, a series of images and clips play over the credits. We watch Mohamedou Ould Salahi with his family, his lawyer, his friend. We see him collecting copies of his books and singing to Bob Dylan’s music. This is standard fare for films based on true stories. After the typically successful battle against the villains of the world, we can sit and comfortably extol the virtues of the real figures that inspired these true stories. Typically, these moments inspire some amount of joy as we tie the reality to the fiction. This time, though, I struggled to marry the warm casualness of the credits with the film that had come before and its real-world implications.

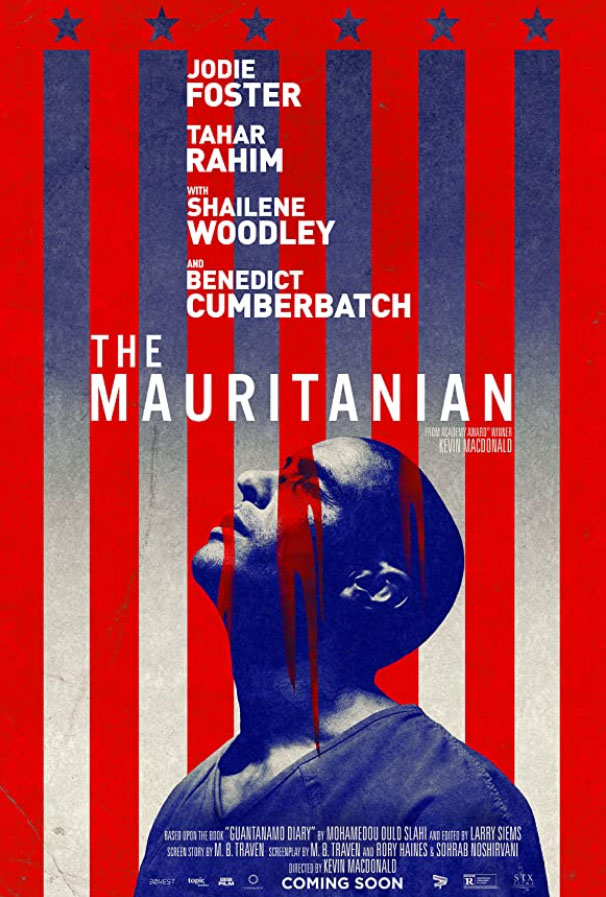

After a brief prelude in 2001 Mauritania where we meet Mohamedou (played by Tahar Rahim) with his family, the story properly begins in 2005 in New Mexico. There we meet Nancy Hollander, a liberal lawyer who has been fighting the government since Vietnam. A case drops into her lap – a man languishing for years in Guantanamo Bay and yet to be charged. He’s been accused of being a recruiter for the 9/11 bombings but the evidence seems scant. He needs a lawyer. Jodie Foster plays Nancy as ambivalent but intrigued. She is not a bleeding heart, but piqued by the idea of needling the government. She takes the case and travels to Cuba with an associate to meet the accused.

When we meet Mohamedou again, it’s been almost 15 minutes since we have seen him on screen. He seems unchanged since we last saw him. He is shackled, and bound but emotionally he retains the charming and cavalier stance from the prologue. He wears a secretive smile as if he’s enjoying a joke that he alone knows. But as the meeting goes on, as Nancy lays out the particulars of her visit – defending him and compelling the government to charge him – the casualness cracks. His eyes dart around the room. His good humour seems more studied and effortful. He tells us little of what has happened since we last saw him, but he agrees to take the duo on as his lawyers. What follows is a legal dance as the pair engage in a legal fight to compel the US court to provide evidence for his arrest.

“The Mauritanian” is a legal drama, and it is concerned with structures and concepts more than persons and emotions as a way of focusing on ideological battles over humanistic ones, a clear intent for the film to be an argument that seeks to objectively convince. It leaves the actors creating characterisations from incidental moments with little interior information. Nancy Hollander is a liberal lawyer with a long history of agitating the government. Her associate Teri (Shailene Woodley) is a young lawyer with parents who seem politically conservative. Nancy’s imminent adversary, Lt Colonel Stuart Couch, is a stickler for rules. And Mohamedou is a personable, good-hearted man in the wrong place at the wrong time. That’s about as specific the film gets in creating interiority from the script – because the film is not really about people, it’s about the systems.

This isn’t about Mohamedou, it’s about the rule of law and it’s about the constitution. It’s a phrase Nancy repeats often. She does not care whether he is guilty or not, but she cares whether the US government should be allowed to do what it does without proper evidence. It’s a noble goal. Early in the film, before we meet Mohamedou in Guantanamo, we meet Lt. Colonel Couch (played by Benedict Cumberbatch), who lost a friend during the 9/11 attacks and will be prosecuting the case. He pledges to bring justice to his friend’s widow. So, the film sets up a battle of two titans with Mohamedou in the middle. Clearly innocent, we assume. Until the information that some years ago he confessed to the crime appears. This is unsurprising for those familiar with the real case or the atrocities of the alleged “anti-terrorist” fight in the US and the plot point is the set up to the sequence in the film that MacDonald has been waiting for.

As the legal battle intensifies in a search for evidence, Macdonald works on turning reading into something visually compelling. And in a flashback sequence (the film is mostly linear but plays around with vignettes of the past filtered through Mohamedou’s memories) we spend some time watching the worst of the torture in a horrific sequence. To call it the best sequence of the film seems accurate but insufficient. It’s also accurate to say the violence and atrocity seem out of place in a film that has centred the generalities of process over the pure visceral nature of torture and human failing.

By this point in the film, Rahim has managed to eke out a full character from scant information. In a herculean way, he crafts a character that is specific even as the film wants to resist being too specific in its development. Because Mohamedou is not a protagonist even in what is his ostensibly his own story, Rahim builds his arsenal from glances – a studied affected casualness with his lawyers; the way his body coils up when approached by interrogators; the way his anger briefly unleashes twice – once at Nancy and then at a translator that tries to console him. It’s not so much that the film is working against him but the film’s investment isn’t in him as a person, but as a figure. Or, more generously, “The Mauritanian” knows that Rahim can fill the gaps of the script, so it leaves him to create interiority that the dialogue refuses to. It’s a lesson in the way performance can build a character. The perfunctory flashbacks to his past feel evocative just for the way Rahim’s face communicates present despair.

His other cast members are not as adept. Cumberbatch, in particular, seems out of place. Not bad enough to disrupt the cadence of the film but not at ease in his role as the Southern lawyer experiencing a crisis of faith in his government. Foster and Woodley are better, if not consistently. Foster’s steely resolve is compelling, but I found myself more intrigued by Woodley, who is given less to do but uses her ability to react to her surroundings to good effect. She leaves the film for the second half and it suffers from her absence. But this is Rahim’s film, even when it feels disinclined to admit this. Because of the through-line of his performance, the film becomes vibrant and real and affecting.

Is it a sign of good filmmaking or a good subject at the way Mohamedou lingered in my mind? It’s not Macdonald’s fault but I found myself wondering how the brief video of the real Mohamedou and the film’s end seemed more aware of him as a person than the film that came before it. – despite Rahim’s best efforts. I also wondered what to make of the very last moment of the film where the real Mohamedou listens rapturously to Bob Dylan’s “The Man in Me” – the ultimate figure of American folksiness — in a film that has only just showed the hate and awfulness of America.

These are complicated questions existing beyond The Mauritanian. And I can’t pretend that some of its images are not particularly searing. The sharp turn into veritable horror movies as we watch Mohamedou’s torture – psychic, physical and sexual – is the film’s most searing. Again, I find myself asking, is it because the filmmaking is sharp or because there’s no way to not feel emotionally spent by scenes of torture that refuse to let you look away. It’s part of the films praxis that the torture is filtered through that scene of the two opposing lawyers two lawyers reading the documents.

But, why do the images of this helpless brown man being tortured cut away to the wincing, tearful eyes of these white protected Americans who will never be put in positions like this? Why must his pain depend on being legitimised by the white figures recognising their systems? Despite specifying the awfulness of the system, “The Mauritanian” does not wade into the deep-rooted racism of the American justice system and its hatred for Muslims. And within that framework, I wonder whether we are meant to be warmed by the friendly guards who Mohamedou values. To its credit, “The Mauritanian” is not a treacly exercise in social justice, but in key moments I found myself intrigued but also frustrated. It’s not my job to say I wish I could see the real Mohamedou in a documentary. Or that a fictional version of his life was not framed as a story of a white woman avenging the system and a white man being moved to rethink his political position. Rahim gives an essential performance in this film, nonetheless. Why should I even critique the film for things it does not set out to do? What do we even want from stories like this? To be moved? To be angered? To be informed? Within the system of American “counter-terrorism” there are people being tortured and dying. Real people. Who decides who gets a story or who gets empathy? How does film navigate that and avoid being lurid in the images that show us the worst of the torture? And is it enough for a film to wrap this up with a dutiful end-credit sequence?

That’s no slight towards “The Mauritanian”. It’s competent. It’s not its fault that North African and Arabian characters still enjoy little interiority in western cinema. It’s not the film’s fault that these stories always feel in service of an American audience that needs to be convinced of the humanity of the people. Do I like “The Mauritanian”? Mostly. Yet it left me feeling unfulfilled. But that’s not the fault of the film. That the film cannot meet the grand severity of its subject is a mere result of inevitable structures of mainstream filmmaking. I can recognise the value of “The Mauritanian” as a fairly competent film that aspires to more than it can achieve. But there’s a sadness that comes with recognising that films like this and like the underseen and undervalued “The Report” (a highlight of TIFF in 2019) will arrive and be seen by a few, while as I sit here extolling the vices of mainstream cinema people are still being held in Guantanamo Bay being wrongfully accused and dying as captives all due to the failings of an American Justice system that refuses to confront its own hypocrisy.

The Mauritanian is available for purchase and streaming on Prime Video and other* platforms.