Editor’s note: This is the first entry in a series, “Sweet Drink: A Preliminary Exploration of the Social History of Nonalcoholic Carbonated Beverages in Guyana (1870–2020),” based on Professor Vibert Cambridge’s research.

This is a preliminary history of nonalcoholic carbonated beverages in Guyana over the 150-year period 1870–2020. It is preliminary because there is still much work to done. It is hoped that this series will stimulate feedback to help to close the gaps in this story about an important aspect of Guyanese life: food and nutrition. We start with a composite snapshot of Guyana’s “sweet drink” market in June 2021.

On Sunday, June 13, 2021, I sent a personalized message to 110 of my Facebook friends who were in Guyana at that time. Many were aware of my ongoing study of Guyanese cultural life, especially my current interest in the multidimensional role of nonalcoholic carbonated beverages—”sweet drink”—in Guyanese life during the pivotal 20th century. So that I could get a snapshot of the accessibility of these beverages to Guyanese consumers, my message included the following request:

Are you going into a supermarket, corner shop, or cake shop over the weekend? If yes, can you observe what sweet drinks (also called nonalcoholic carbonated beverages, aerated drinks, or soda) are available. If possible, please take a photo or two.

By Friday, June 18, 2021, my Facebook friends had sent me 224 photographs taken in supermarkets, consumer co-operatives, soft-drink retail outlets, shops, pharmacies, restaurants, gas stations, confectionary stands, cool-off spots, roadside vendors, and private homes in urban, suburban, and rural communities in Deme-rara, Berbice, and Essequibo. In addition to providing evidence of the “sweet drinks” that were available for purchase, these photographs also included evidence of the range of non-carbonated nonalcoholic beverages on sale. These included concentrates, energy drinks, flavored drinks, juices, teas, and water.

Altogether, 300 hundred brands were identifiable in the 224 photographs. Almost 30 percent were “sweet drink” brands. They included Busta, Canada Dry, Coca-Cola, Dr. Pepper, Fanta, I-CEE, Mountain Dew, Pepsi, Slice, Soca, Solo, Sprite, Thrill, Vimto, 7 Up, and a “small lemonade.” Almost 40 percent of the brands were non-carbonated fruit-flavored drinks, such as Ocean Spray, Minute Maid, Quenchers, Splash, and Sunny D. The composite snapshot revealed that nonalcoholic carbonated beverages (also called sweet drink, soft drink, aerated drink, soda, or pop) are alive and significant in contemporary Guyanese life. Consumers appear to have access to a wide variety of domestic, regional, and international brands. The companies with “sweet drink” operations in Guyana are ranked among the top 100 companies in the Caribbean.

Sweet Drink: A Preliminary Exploration of the Social History of Nonalcoholic Carbonated Beverages in Guyana (1870–2020) tells the story of fizzy nonalcoholic beverages. It is a complex story. It is a story about human responses to thirst in a hot and humid place. It is a story about immigration, entrepreneurs, and charismatic leaders. It is a story about cultural change, especially the role of disruptive technologies and the manufacture and maintenance of taste cultures. It is also a story about discourses on respectability, hygiene, and public health. It is a story of the interrelationship between economics and politics in post-World War II Guyana. Therefore, it is a story about Cold War geopolitics, franchise capitalism and political ideologies, modernization, national development, regional integration, and socialism. In the 21st century, the sweet drink story has highlighted diaspora engagement and, in the case of the “small lemonade,” product resilience.

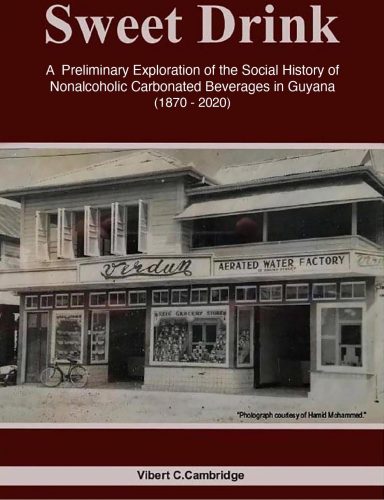

As previously mentioned, these fizzy nonalcoholic concoctions are also called sodas, aerated drinks, soft drinks, and pop. These terms will be used interchangeably in this series. These terms are loaded with significant sociological and geopolitical data. They are useful for trying to understand the zeitgeist, the spirit of the time. Aerated drinks and soda (water) are associated with the early years of the industry in British Guiana. This is reflected in the names of the bottling establishments. For example, a 1914 U.S. Department of Commerce report noted the presence of the Niagara Soda Water and Royal Crown Soda factories in Georgetown. The term “aerated drink” appears to have been introduced during the 1930s. It is evident in the names of companies, such as the Verdun Aerated Water Factory.

“Soft drinks,” the formal term for these nonalcoholic beverages in the United States, might have arrived in Guyana during the 1940s and 1950s, when the major U.S. brands entered the colony’s marketplace. The vernacular term “pop,” which is also of American origin, has grown in popularity since the 1960s, especially with the introduction of canned beverages with their characteristic popping sounds when the tab is pulled.

One of the vectors for this term in Guyana is Guyanese immigrants in the United States. Since the 1960s, there has been increased Guyanese immigration to the United States. A characteristic of this group is the tendency to make regular trips to the homeland. Among the rituals of return is the use of American-isms, an indication of living abroad or having “been to.” So, it is not strange to hear, “Let me have a can of pop,” or even a “bottle of pop.” Anticipating migration, many Guyanese at home also adopt these Ameri-canisms. At the end of the first decade of the 21st century, almost 200,000 Guyanese were living in New York. Altogether, there are probably 1.5 million Guyanese living abroad. In 2020, it was estimated that the resident population in Guyana was approximately 786,000.

Guyana has a multimillion U.S. dollar “sweet drink” industry. Data from Guyana’s Bureau of Statistics show transactions (domestic production, exports, and imports) of more than US$668 million (approximately GY$133 billion) between 2007 and 2018.

This story about “sweet drink” in Guyana starts with small-scale community-based entrepreneurs using hand-cranked technologies and concludes with the current artificial intelligence (AI)-driven automation at the Banks DIH bottling plant in Ruimveldt, Greater Georgetown, Guyana. Along the way, the story discusses the dynamics of this aspect of the nation’s industrial and manufacturing life. It highlights the ascendency of bottlers (e.g., Banks DIH), the emergence of new domestic and regional players in the Guyanese marketplace, and the persistence of “small lemonade” in the face of the major global brands. Sweet Drink is also a story about the groundbreaking marketing strategies of I-CEE, Pepsi, Coca-Cola, Red Spot, and other brands in their quest to expand and dominate British Guiana’s “sweet drink” market starting during the 1940s and (at an accelerated pace) the 1950s and 1960s.

Aerated drinks are intertwined with Guyana’s social, cultural, economic, and political life. Bottlers, such as Wieting & Richter, Banks DIH, Rahaman Soda Factory, and Demerara Distillers Ltd., have played a significant role in that milieu. However, the small community-based operators who pioneered the industry in the urban wards, rural villages, and hinterland communities have also earned a place in Guyana’s grand story.

The “sweet drink” story brings us close to Guyana’s histories of international trade, immigration, disruptive ideas, economic and technological innovation, urban development, food and taste cultures, consumer demand creation, brand loyalty, and charismatic leaders, especially during the pivotal 20th century. Like Musical Life in Guyana: History and Politics of Controlling Creativity, Sweet Drink is another effort by the author to make accessible available information about understudied and underexplored aspects of the long Guyanese experience. It is a response to the call from John Campbell for a Guyanese historiography that explores “aspects of history which are considered unimportant by many because they concern facts of a small sector of the total community.” Campbell made that call in his 1987 book, History of Policing in Guyana. Like that work, Sweet Drink is a story that is “interlaced with the history of Guyana as a whole, and to such an extent, that without it, history of the Country would be far from complete.”

The study of Guyana’s social and contemporary history is invigorating. The emersion in and collection of the data provide many moments of epiphany. So far, the data on nonalcoholic carbonated beverages in the Guyanese experience have been compiled from online sources and depositaries in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Guyana. They include the microfilm collection of Guyanese newspapers in Ohio University’s Alden Library and records at the University of Guyana library, the National Library of Guyana, and Guyana’s Bureau of Statistics. Other sources are the private collections of overseas Guyanese, correspondence with executives at Banks DIH and Demerara Distillers Ltd., focused conversations on Facebook and with Facebook friends, in-depth in-person interviews, photographs from family archives, and data collected by my daughter Omadella Shalla Cambridge-Harper.

Fires, the climate, and neglect have destroyed significant documents and other materials that would help us to develop a more granular understanding of the industry. However, memories, artifacts, and documents in archives and private collections were helpful.

Sweet Drink is a story about human encounters, interactions, and exchange in multiethnic Guyana since 1838, the year that enslaved Africans were emancipated and the beginning of the state-sponsored importation of indentured laborers. This moment is recognized as the start of the modern Guyanese society.

Over the next 16 weeks, we will explore this story of “sweet drink” in Guyanese life. The aim is to review the 150-year history of this industry. We will meet the pivotal “sweet drink” entrepreneurs and their businesses. We will also look at their responses to the political, economic, and cultural forces that influenced life in Guyana during the 20th century.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Cambridge, V. Musical Life in Guyana: History and Politics of Controlling Creativity. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2015.

Campbell, J. History of Policing in Guyana. Georgetown: Guyana Police Force, 1987.

Fry, C and Carrie Spector, Kim Arroya Williamson, and Ayela Mujeeb, Breaking Down the Chain: A Guide to the Soft Drink Industry. New Jersey: ChangeLab Solutions, 2012.