There’s an undercurrent of restrained anxiety throughout the six episodes of the new Netflix miniseries, “The Chair”. It’s a tension that’s pulsating, but not quite explicated. A wound on the verge of rupturing.

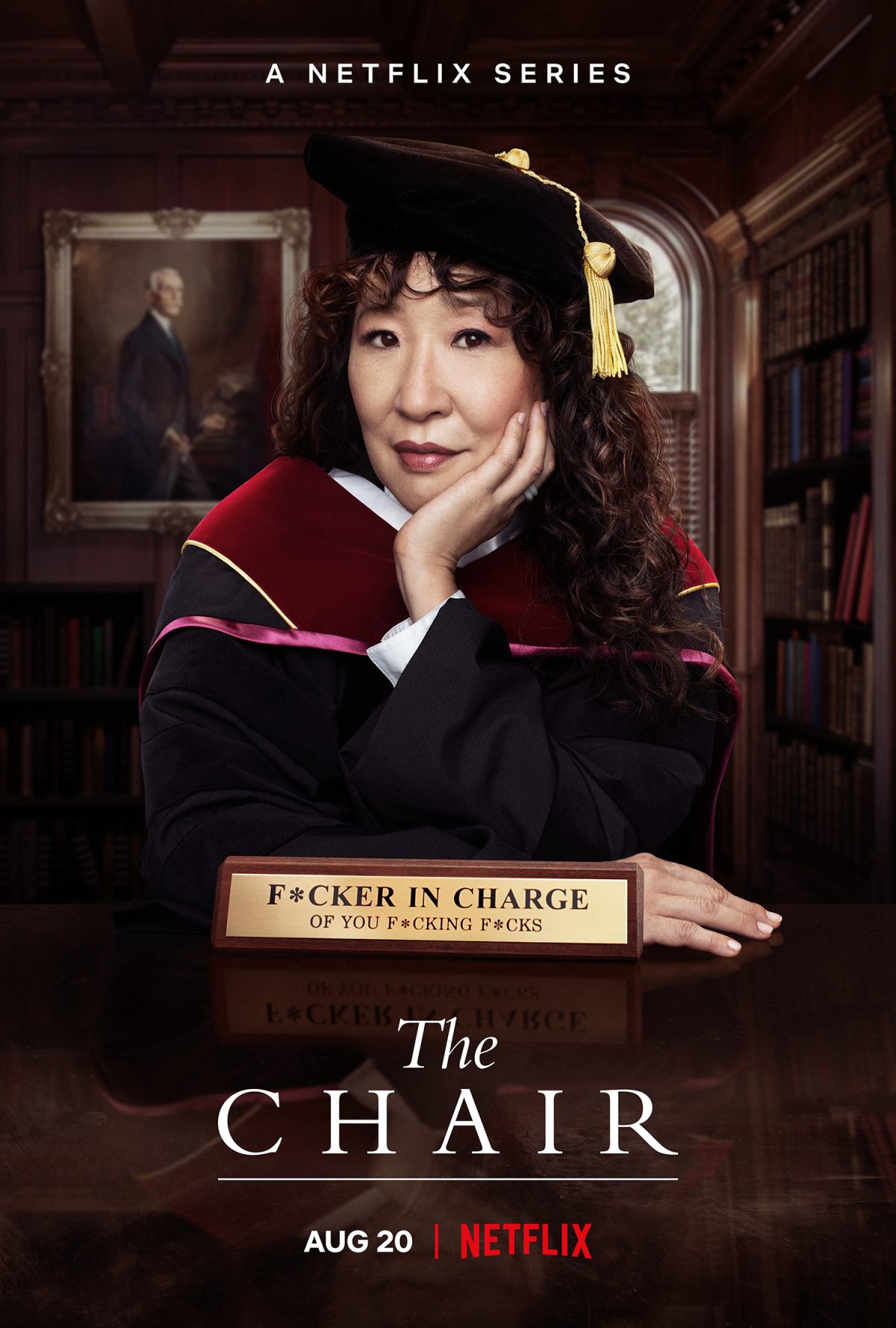

It makes sense both within and without the world of the show, which covers the first few weeks of Dr Ji-Yoon Kim’s term as the Chair of the English department at the prestigious Pembroke University. As we watch Ji-Yoon navigate the trials of her role – she is first female chair of the department, and one of the few non-white staff members – her experiences are funny in familiar ways. They also become bitingly satirical and, in moments of heightened drama, there are waves of sadness that emerge in unexpected ways.

When it was announced earlier this year, academic Twitter was abuzz about what a long-form depiction of an English department might even look like. Would this Netflix filtered reality of academia present the world with glamorous inauthenticity? Television has been littered with glamourous versions of familiar jobs – sexy doctors, svelte lawyers, and pinup policemen. With “The Chair”, academics were now at the forefront. But, how much reality could there be in a fictional show? Even more, though, how much reality do we even need?

“The Chair” is not a documentary. It’s a TV show, and each of the six 30-minute episodes is a precise glimpse into a particular mutation of that recurring tension – things are amiss in higher education. Yes, there’s more than just that. “The Chair” extends beyond academia. But academia is at its centre, in moments that resonate, and then unsettle and then haunt, it feels like it bears witness to uncomfortable crises that feel all too familiar for those in academia. The humanities are in crisis after all… or, so we keep on hearing.

“I feel like someone handed me a ticking time bomb because they wanted to make sure a woman was holding it when it explodes,” Ji-Yoon complains to a sympathetic colleague in an early episode. The department’s budget is dwindling, staff are being paid too much to justify the low enrolments, and students are disconnected from the dead writers they are studying. Things go from bad to worse when Ji-Yoon’s widowed colleague and kind-of-friend/kind-of-old-flame Bill, (a very-good Jay Duplass) loses the faith of his students with an ill-timed mock Nazi salute. The students protest what seems, to them, a careless disregard for the seriousness of right-wing ethos. The faux-pas becomes a full-blown crisis and that ticking time bomb detonates.

A few years ago, I began the early stages of research exploring representations of academia in film and television. I never finished the project, but I was fascinated by initial trends I noticed. In many contemporary presentations of academia – especially of the humanities and particularly English departments, there seemed to be a distinct resentment for academia itself, whether a sheepish tone of apology for it, or exhausted “ya-got-me” wave of admitting that there wasn’t much there. The humanities are dying, they would all announce. Or, already dead. Each work would start from a position of hyper defensiveness itself. But if every representation of the humanities started off with a disclaimer, then the case was already lost. “The Chair”, to its credit, feels more perceptive than that.

“The Chair” does something that I feel is all too rare in televisual mediums, a landscape that already rarely really looks at academia. It captures the humanities in academia not as an abstract concept or noble calling but as a job that comes with fine print and requirements beyond the graceful.

In a late episode, Ji-Yoon’s father tells a story of her choosing her destiny in a Korean tradition for babies. She chose a pen, making her destined for literature. And it’s a lovely moment, but that destiny is bound to the reality that for a department to function it needs to recognise that the real world and the abstract ideologies of the humanities must work in tandem with each other rather than in competition. Later, Ji-Yoon tries to explain to her daughter why she really chose her field, rather than something a little more pragmatic. In the tense scene, we see Ji-Yoon listening to herself speak and realising the answer of “choice” is much more complicated than a tidy answer.

Many works of art, not just those about academia, have wrestled with the tension between the heart and the mind. The true artist, the true Humanities’ lover, wants to do more than bureaucracy. They want to be in the “real” world not in the bubble of higher education. But academia is the real world, for all its good and especially for all its ills. “The Chair” gets that. In ways that are not always pleasant to experience.

In a moment of uncomfortable serendipity, I watched the episode of “The Chair” on the day that I received an appointment letter to be the head of my humanities department. As I watched Ji-Yoon realise that intention does not always follow through to actualised, that the bureaucracy of leadership in academia defines our work, and that there would be a recurring negotiation between different versions of herself as nominal “leader” against changing dynamics with colleagues, it felt like looking into a fractured mirror. By the last two episodes, I felt like “The Chair” was closer to psychological horror than anything else, watching some moments with intense nervousness through my fingers—for the characters within the story, but also for the show which I found myself identifying with and rooting for.

In her first department meeting, Ji-Yoon announces the dire situation the department is in. Enrollments are down and budgets are gutted. This is a familiar song for humanities departments everywhere. “We have to prove that what we do in the classroom, whether modelling critical thinking, stressing the value of empathy, is more important than ever and has value to the public good,” she says. True words, yes, but it felt too generic. Too much of the familiar refrain that the humanities teach people to be better and more empathetic humans. Yes, they can. But sometimes, many times, they don’t.

The halls of humanities departments are littered with many jerks and despots and tyrants. The humanities as a gateway drug to self-actualisation and empathetic thinking is its own academic myth. Ji-Yoon’s opening speech of the value of the humanities made me nervous for how textbook it sounded, with a generic Harold Bloom quotation to top it off. But “The Chair”, mercifully, becomes savvier than my initial circumspection gives it credit for. It supports much of what Ji-Yoon says, but it also deconstructs it. In a later episode, another lecturer talks about loving a poem just for its worth as a poem, and I let out a breath I didn’t realise I was holding. Poems, and novels, and art exist as part of society. Studying art and the humanities matter for the mere fact that they exist in our world. And their very existence is enough to make them worthy of being studied.

Because so much of the show’s crisis is academic – in the literary sense – the series is one that is more beholden to its script than its direction. But, “The Chair” – if not visually flashy – is incredibly perceptive about notions of space and proximity. Director Daniel Gray Longino establishes context in pronounced moments of silences (shots of Ji-Yoon’s family photos, a sweeping shot of books on office tables, bathetic moment of awkward glances from characters in silence). There’s a really striking moment where we watch Bob Balaban’s Professor Elliot Retz (a distinguished professor set in his ways and realising he’s no longer as compelling to students) observing Nana Mensah’s Professor Yaz McKay in a moment of fraternity with her students. It’s part of a nuanced arc where the two clash. Retz must confront his resistance to change, micro-aggressions of race and gender. The moment is very much about the looks on the actors’ faces, but it is also about the way that Longino directs them, about the very specific way the camera is mining those faces for an ambivalent anxiety where I found myself uncertain how to feel about these situations. We understand and empathise with Yaz, the only Black woman in the department, and her exhaustion at the limits placed on Black women. But, in moments that complicate our choosing of “sides”, in moments of silence that depend on Longino’s direction, a sadness comes through in waves. The ageing professors at the helm, resistant to ceding power, are sadder and more pathetic rather than villainous.

That sadness is a key part of what makes the centre of “The Chair” feel so familiar and relevant, even as many who watch it will be unaware of what the “inside” of academia looks like for a frame-of-reference. But, as Peet has said of the show, any old institution – regardless of the field – is struggling to find its place in the contemporary word. And that awareness gives “The Chair” moments of great specificity that also feel to be speaking beyond academia.

There’s a really great arc where Holland Taylor’s Professor Joan Hambling approaches a complaints unit of the university – first for a technical matter, then later for a more personal claim. She’s alarmed at the attire of the young woman handling her case, the young woman is in turn less than enthused by her perception of Hambling’s rudeness. But within their clashing dynamics, there’s a shared moment of women and as Taylor tries to verbalise her despondence, the sadness pours, sadder for the way Peet slyly writes it as a deflection rather than a full-throated bit of tragedy. In a moment of desperation, she admits, “I just want someone to acknowledge what happened!” A humble desire. But who’s paying attention? Disappointment on the periphery. Many conversations about the failure of academia in the Global North centre its issues on the whiteness of the academy globally, and particularly the whiteness of alumni. Watching “The Chair”, though, and recognising my own experiences of academia – in a university of very few white colleagues – was a reaffirmation that the exigencies of the worst of academia transcend the Global North and issues of white fragility.

To be in academia is to realise that ambivalence and doubt coexist with a desire for knowledge and an affinity for creativity. In an interview for the show, Sandra Oh intelligently surmises the way that academia can be tiresomely behind the times, but all the while it wants to be and sometimes can be at the forefront of so much progressive thought in other ways, sometimes at the same moment. “The Chair” is not nominally trying to be a piece that bears witness to academia centrally, not really. Yet, in its final episode Ji-Yoon and Bill sit and discuss his future in academia and in a roundabout way it feels like a tentative affirmation. Bill pledges his commitment to teach. It’s something he has to do. But it’s not a stereotypical affirmation of teaching changing the world. Instead, this moment comes differently.

“The Chair” does not shy away from the exhaustion. There are no glamorous professors here (although Nana Mensah plays the kind of eclectic professor whose classes I wish I could sit on). It is not quite what you expect it to be, whatever you might expect. It’s particularly unwilling to give us complete tragedy, or any true sense of hopeful success. It’s somewhere else, in the middle, not quite ambivalent but full of perceptive glances. There’s clarity in those moments of perception that is harder to read, but with nuances and moments that feel bound to linger.

A final moment of a character ascending up the ladder of hierarchy is presented as hopeful in some respects, but we have watched the preceding episodes and I suspect even the creators know that it cannot be as triumphant as it might seem. At every step, “The Chair” seems to be asking us to look through it to the meaning behind the meaning. Not to be blindly amused by the hijinks of the characters, nor to be completely debilitated by the hopelessness of their faith. Instead, in a way that gently surprised, “The Chair” ends quietly with an ellipsis. What now? It asks. A second season would be a gift. This story isn’t over. Same for academia. There’s more to do here. I want to see that. The six episodes of “The Chair” feel like the beginning of something great.

The Chair premieres on Netflix on August 20.