By the 1970s, cakeshops and cakeshop–salt goods shops, rather than soda fountains (as anticipated by the U.S. consul in 1924), were the primary outlets for nonalcoholic carbonated beverages. Cakeshop–salt goods shops were at almost every intersection in the urban areas. Cakeshops and grocery outlets were in every village and settlement in the rural areas. A variant was also evident in many hinterland settlements. Most of these businesses were connected to the Banks DIH distribution network. This distribution infrastructure was used to deliver a fortified food: Puma, a product that evoked fond memories for many Guyanese, even in 2020.

The story of Puma began in 1965 as an international response to a global problem: malnutrition, specifically the protein crisis. The early post-World War II era revealed the scope of malnutrition, and a manifestation of poverty, especially in the developing world. A United Nations Development Programme index listed the multiple dimensions of poverty. They included health (e.g., infant mortality and nutrition), education (e.g., enrollment and years of education), and living standards (e.g., access to potable water, sanitation, cooking fuels, and electricity).

The pervasiveness of poverty in the developing regions of the world was identified as the condition that made those societies fertile ground for communism to take root. Thus, during the Cold War, the United States funded many aid and development programs to address this complex problem. One solution was a superfood to address hunger, the most egregious manifestation of poverty. The focus was protein deficiency.

Between 1950 and 1970, the daily supply of protein in Guyana was below the standards established by United Nations agencies. As was the case in many developing regions, carbohydrates, especially those that were sugar-based, were the primary energy-giving options. Sydney Mintz referred to this as “the proletariat hunger fighter” strategy. The previously mentioned 1960 Government Analyst Department report indicated that sweet drinks served that function in the colony. In 1960, there were 31 registered aerated beverage factories in the colony, and each pint of beverage contained 2.5 oz of sugar. There were concerns about the consequences for the nation’s health.

In the international development community, soya beans were positioned as the “super food” to mitigate protein deficiency. The challenge, however, was the culturally appropriate delivery of soy protein to developing regions without a history of soy consumption. Guyana was to be a model for accomplishing this through a franchise relationship between Banks DIH and Lomond Ltd., a subsidiary of the Monsanto Company (St. Louis, Missouri), a “diversified international corporation.”

According to George Armenta, Monsanto’s area marketing representative resident in Venezuela, in 1965, his company aimed “to produce an economical, good-tasting beverage that would supplement diets deficient in proteins and essential vitamins and minerals.” The July 13, 1968, Guyana Graphic carried a story captioned “Puma is coming your way soon.” It included Peter D’Aguiar’s announcement that after market research and testing earlier in the year, Monsanto had awarded DIH the franchise to bottle, Puma, the “economical, good-tasting beverage.”

Peter D’Aguiar described the beverage as “nutritious, refreshing, and valuable” and appropriate for “help[ing] to satisfy the nutritional needs of the people of Guyana.” At that time, several products were being marketed as nutritious food supplements. However, none was in the form of a soft drink. This was an innovation.

By 1968, Monsanto’s Hong Kong-based subsidiary had developed a powder concentrate based on “isolated soy proteins.” It included banana flavor, sugar, and vitamins. Puma was shelf-stable. Under the franchise agreement, the concentrate was shipped to DIH where it was “packed in a glass bottle with a crown cap.”

This development was hailed as a revolution in fortified food. The strategy tapped into existing consumer behaviors in the developing world. These societies were characterized as having a “relatively high consumption of soft drinks.” It was also an effective system to deliver the fortified food. DIH, Guyana’s leading bottler in 1968, had the technological and operational infrastructure: a modern bottling plant and a national distribution system. Puma in Guyana was therefore an experiment to test consumer acceptability of a soy-based product in a non-soy culture in the developing world.

Puma, a noncarbonated drink, was packaged in bottles similar to those used for conventional sweet drinks. The aim was to replicate the success of Vitasoy, which, by 1962, “had become Hong Kong’s best-selling soft drink, ahead of such internationally known brands as Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Seven-Up.” Describing the roll-out in Guyana, George Armenta reported:

The product was promoted to the consumer as the “Refreshing New Super-Energy Soft Drink Packed with Proteins and Vitamins.” This theme was repeated in radio, newspaper, and cinema advertisements. The terms “refreshing,” and “soft drink” connoted fun and pleasure. The use of “energy,” “protein,” and “vitamins” suggested health and nutrition. In all promotional copy, an effort was made to give equal importance to both themes.”

During the week of March 9, 1970, the New York-based consumer research company Oxtoby-Smith conducted a study in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital, to measure consumer reactions, including motivations, regarding Puma. They interviewed a random sample of “a total of 617 Georgetown residents (12 years of age and older).” The “sample was divided into demographic groups, according to the population of Georgetown. By March 1970, “PUMA was the second best-selling soft drink in Guyana.” According to the study:

[It was] positioned by the consumer as a “healthy soft drink.” It was consumed for its perceived health benefits as well as taste … taste alone was not the major motivation to drink Puma. Consumers reported that since they began drinking Puma, they have been drinking less of other beverages—especially other soft drinks. The high level of acceptance of PUMA by the Georgetown consumer is indicated in his willingness to pay slightly more for the protein beverage. Obviously, PUMA has been well accepted as a soft drink, and the “health” theme has proved to be a strong motivator.

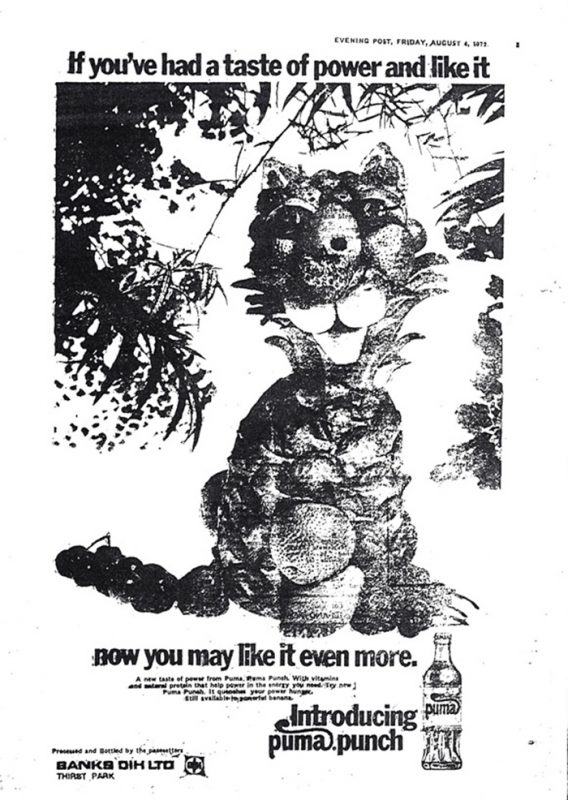

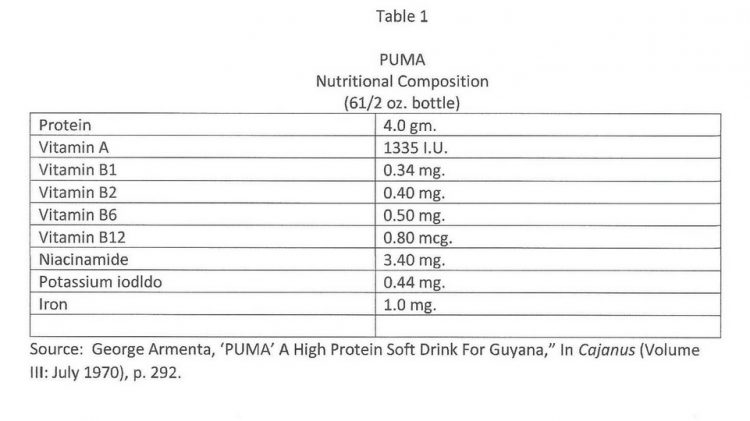

In 1972, an analysis of the Puma experience in Guyana was published in the contemporary trade press. It incorporated three years of data and reported success. It confirmed the benefits of using DIH, Banks DIH since 1969, because of its franchise experience and effective distribution system. Banks DIH reported sales of more than 29 million bottles per year in the early years after the launch of the product. This exceeded expectations. In 1972, a new flavor, Puma Punch, was added. Table I provides the nutritional composition of Puma as provided by George Armenta in his article “PUMA A High Protein Soft Drink For Guyana,” which was published in Cajanus, the Caribbean Food and Nutrition Institute pioneering quarterly journal.

The three-year analysis of the Puma experience also supported the proposition that the “relatively high consumption of soft drinks in the developing world” made the packaging of soy as a soft drink effective for delivering the super food to the developing world. The product remained in production until 1976, the year of dramatic economic decline, which had significant consequences for the entire nation.

The origins of this situation can be traced to February 23, 1970, when Guyana adopted a republican constitution and became the Cooperative Republic of Guyana. This marked two historic achievements: the first republic in the Commonwealth Caribbean and the first republic in the world to be based on the cooperative. Both actions were articulated as acts of decolonization and the establishment of an economic system inspired by self-reliance.

Coupled with both actions was the refashioning of the country’s foreign relations. By 1973, Guyana had established diplomatic relations with the U.S.S.R., East Germany, China, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and the Republic of Cuba. With the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Republic of Cuba, Guyana became a member of the socialist bloc in the Americas. These actions would lead to a rapprochement between L. F. S. (Forbes) Burnham and Cheddi Jagan under the rubric of “critical support.”

Coterminous with the establishment of relations with the socialist world, Guyana played an active role in developing the mechanisms for Caribbean integration. In 1973, Guyana’s Prime Minister, Forbes Burnham, Q.C., along with Prime Ministers Vere Bird of Antigua, Michael Manley of Jamaica, Errol Barrow of Barbados, and Dr. Eric Williams of Trinidad and Tobago, took the critical steps to establish the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM).

In 1974, at a special congress of the People’s National Congress (PNC), Prime Minister Burnham announced one of the most consequential policy decisions in Guyana’s post-independence history. The speech not only acclaimed the PNC as the dominant political institution in the land, but it also declared that Guyana was on the path to becoming a socialist state. In addition, the nationalization of the “commanding heights of the economy” was proclaimed a key element. In 1971, the Guyana government began the nationalization of the bauxite industry. The first company to be nationalized was the Canadian-owned Aluminum Company of Canada (ALCAN). The last was the American-owned Reynolds Metals Company in 1974. In 1976, the sugar industry was nationalized.

In 1976, the nation’s constitution was amended, and Forbes Burnham became the nation’s first executive president, a position that he retained until his death in 1985. Burnham’s political and economic decisions fractured relations with the United States. There was an immediate and dramatic reduction in aid: from a high of US$18 million in 1968 to US$0.2 million in 1974. At the 1976 rally to announce the nationalization of Reynolds Metals Company, President Burnham “asserted that the United States had tried to block World Bank loans for Guyana’s sea defenses and that Guyana had eventually secured a loan with the help of Canada, India, Mexico and other nations.”

The economy ground to a halt. Other influential factors were the spiraling cost of imported fuel because of the OPEC oil embargo, the depletion of the nation’s foreign currency holdings because of the investment in the Mazaruni hydroelectric project, difficulties in obtaining loans from international agencies (e.g., the World Bank), and the “conditionalities” of the International Monetary Fund.

The government resorted to imposing foreign exchange restrictions and banning the importation of several commodities, including traditionally imported foods, such as wheat flour. This had a deleterious effect on the sweet-drink industry. As stated in recent installments, restricted access to hard currencies starved the industry of raw materials, especially syrups, essences, bottle caps, bottles, and machine parts. It crippled the small community-based operators and many large operators. The bottlers were unable to maintain their franchises. Among the early casualties was Wieting and Richter, which sold its Coca-Cola franchise and operations at the Ruimveldt Industrial Site to Banks DIH in 1975.

This economic situation probably explains Banks DIH’s decision to stop bottling Puma sometime after 1976. For a period in 1985, Banks DIH ceased production of its entire sweet-drink line because of its inability to acquire foreign currency to purchase crucial inputs. Carlton Joao, the current Sales and Marketing executive, noted, “After Banks lost the Pepsi contract, it had to innovate to keep the line going with Black Cherry and Carambola drinks, among others.” Between 1976 and 1992, popular international brands, such as Pepsi, Coca-Cola, and 7Up, were not produced in Guyana. However, they remained available because aerated drinks were among the commodities smuggled into Guyana.

President Burnham died in August 1985. This led to the unravelling of the socialist experiment and the start of a new economic era under the presidency of Hugh Desmond Hoyte (1985–1992). It also marked a new chapter in Guyana’s sweet-drink story. Peter Stanislaus D’Aguiar died in London on Thursday, March 30, 1989. He was succeeded by Clifford Barrington Reis. This heralded the dawn of a new era in the company’s history. Banks DIH would face new competition.

Thirst in a Hot and Humid Place

The apparent insatiable demand for aerated drinks in the heat and humidity, along with the CARICOM trade policies, encouraged new domestic and regional players to enter the Guyana sweet-drink marketplace during the early 1990s. By 1992, the new economic ethos had been consolidated. The socialist rhetoric was jettisoned, many of the nationalized industries and companies were privatized, and there was political change.

Before we look at the new political economy and the new players in Guyana’s soft drink marketplace after 1992, we shall explore a hybrid in the Guyanese beverage story: alcoholic–nonalcoholic beverage mixes. Banks DIH’s alcopop, Shandy, gives a nod to the small brown and green bottles. The origins of this beverage can be found in the mixed-drink tradition, which includes Bankle and Baby Bubbly. In the next installment, we shall examine an outcome of this tradition.

Selected References

Armenta, G. “Puma, a high protein soft drink for Guyana.” Cajanus (Volume III: July 1970), pp. 289-292.

Burnham, L. Declaration of Sophia. Address by the Leader of the People’s National Congress at a Special Congress to Mark the 10th Anniversary of the PNC in Government. Georgetown: People’s National Congress, 1974.

Cambridge, V. Facebook conversation, “The Geography of ‘Sweet Drinks’ in Guyana” launched April 21, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/vibert.cambridge/posts/10157045271290849?comment_id=10158058760755849¬if_id=1624887773436591¬if_t=feed_comment&ref=notif

Jagan, C. Critical Support: Straight Talk, September 14, 1975. Available online at: https://jagan.org/CJ%20Articles/In%20Opposition/in_opposition7.html#2512

Johnson, L. President’s Foreword to A Report of the President’s Science Advisory Committee on the World Food Supply. Volume 1. Washington, D.C: The White House, May 1967. Available at: https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/the-presidents-foreword-the-report-the-world-food-panel-the-presidents-science-advisory

Majeed, H. Forbes Burnham: National reconciliation and National Unity. New York: Global Communications, 2005.

Shurtleff, W., & Akiko Aoyagi. History of Soybeans and Soyfoods in South America (1884–2009): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook. California: SoyInfo Center, 2009, p. 150.