This column is the third in a series of essays exploring various aspects of the Guyanese financial system. I have done a lot of research on money, banking and financial markets, as well as the accompanying monetary theories underpinning them. I have taught a course titled Money, Banking and Financial Markets for fifteen years. I was even the monetary theorist advisor to a technology start-up trying to build a cryptocurrency. It is surprising how the best computer programmers are mystified by monetary theory as much as I am with complex computer codes. In spite of this background, I still find it difficult to write on these topics for a popular audience.

The prompt for writing these columns comes from a brilliant presentation by Mr. Winston Brassington, who argued in favour of the commercial banks expanding credit to the private sector by lowering their interest rates. The sporadic accusation from activists that the banks in Guyana are discriminatory has also motivated this series. I sought to clarify that if we are going to make such a sweeping claim, then let us first consider how banks actually work as it relates to dealing with information imperfections, which are endemic in banking, financial and insurance markets.

The first column in the series made the point that the political leaders have failed to establish the financial institutions that can play a social role in accepting greater risk of default, since extending credit to non-traditional borrowers to pursue business activities will result in higher defaults. Instead, this country privatised all its banks, which are now meant for providing private returns. Some entity has got to assume the social role of accepting an above average degree of risk. No such bank exists at the moment because the politicians of this country did not ask the question of what it will take to bring marginalised borrowers into official financing.

In this column, we will address the issue of whether the private banks can reduce interest rate, expand credit and simultaneously increase profitability: the Brassington thesis. It is well known that the banking system in Guyana is characterised by a few dominant banks: an oligopoly. The same feature exists throughout the Caribbean and beyond. In such a situation, deposit rates are low while loan rates are high – hence, there is a high interest rate spread.

As we ponder the Brassington thesis, it important to consider the operational incomes and costs of banks. Interest income on loans is the largest component of bank income. For example, in 2020 the banks earned a combined total of G$31.1 billion in interest income, as well as G$31.4 billion and G$28.8 billion in 2019 and 2018, respectively.

It turns out that making loans is not the only aspect of bank operations. They are also active traders in the foreign exchange (FX) market, buying and selling foreign currencies, such as the US dollar, euros, Canadian dollar, TT dollar and others. These trading activities account for the second largest category of operating income for 2018, 2019 and 2020. Specifically, the banks earned G$3.895 billion, G$4.289 billion and G$4.293 billion in FX sales for 2020, 2019 and 2018, respectively.

The third largest category of income comprise of fees and commissions. For the same three years starting from 2020, the banks made G$3.87 billion, G$3.463 billion and G$2.737 billion. Operating earnings were also realised on other smaller miscellaneous categories, which I will not mention here.

On the side of operating expenses, salaries and other staff-related costs were the largest component amounting to G$7.11 billion, G$7.484 billion and G$6.74 billion. Interest expenses accounted for the second largest category of operating costs: G$4.324 billion, G$4.238 billion and G$4.258 billion for respective years. Several expenses are grouped together in a miscellaneous category. Although not spelled out, the miscellaneous category involves expenses on energy, replacement of machines and computers, among others.

Finally, there were relatively small provisions for bad loans and there were foreign exchange trading losses. While FX trading losses as a category was comparably small, it jumped precipitously to G$2.381 billion in 2020 from the previous year’s loss of just G$132 million.

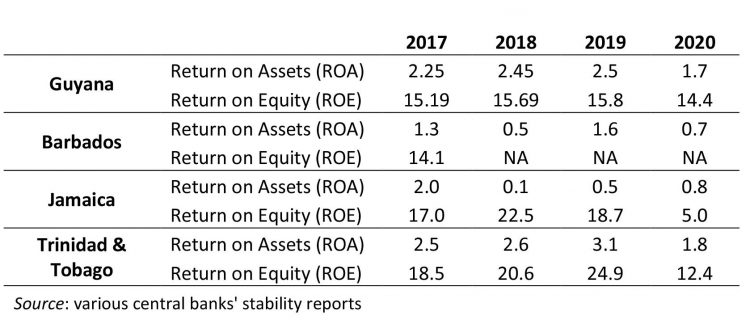

Overall, as one would expect from an oligopolistic banking system, the banks are quite profitable amounting to aggregate profit (after tax) for the years 2020, 2019 and 2018 as G$11.618 billion, G$14.85 billion and G$13.348 billion. However, exactly how profitable are Guyanese banks? It would be helpful to ponder the return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) for a few CARICOM countries. I quickly scanned the following countries’ (seen in the Table) central bank websites and came up with the data presented herein.

In terms of ROE, banks in Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago (TT) appear to be slightly more profitable, although the annual returns for Guyana appear more stable. One reason for the volatility has to do with the higher degree of financialised asset base of TT and Jamaican banks. Jamaican banks, in particular, are quite dollarized in terms of loans and deposits – hence, these assets and liabilities are susceptible to sudden changes in the FX rate. The Guyanese banking system is much more secure given the virtually non-existent asset and liability dollarization that I hope will stay that way. Dollarization is a sure way to sacrifice whatever slim monetary sovereignty small economies may possess. As it relates to the ROA, Guyana’s banks appear to be doing well, coming in just behind those in TT.

Whether Guyanese banks could increase profitability by lowering interest rates a few points should be considered. First, there has been a slight appreciation of the Guyana dollar in recent months. This means that the local currency value of FX will be lower and could stay this way for some time given the oil and gas boom. A likely consequence is banks would not want to venture into unknown lending territory in the coming months and years unless government provides some form of subsidy. As noted above, the banks have already incurred their largest FX trading loss of G$2.381 in 2020. Any marginal expansion of bank loans will be to the traditional sectors and the well-collateralised oil and gas companies. The scenario I describe here is a financial channel of the Dutch disease, which has not been explored.

Secondly, whether banks can increase profit by lowering price (interest rate) depends on a nerdy concept from microeconomics known as the elasticity of demand. Netflix, for example, understands this concept quite well because it has a team of econ PhDs estimating these elasticities and other relationships. That’s why the company has been confident that it can raise its price and still keep its customers. In the case of Guyana, I am not aware of anyone estimating the loan elasticity of demand. However, if I were to bet, I would put my money on an inelastic demand for various reasons. In that case, if the banks collectively reduce interest rates, they will earn less profits, not more.

Nevertheless, the income elasticity – which also was not estimated and another nerdy idea – will kick in at some point. As the income level of Guyanese households and businesses rise, the banks will voluntarily expand loans at current interest rates – making more profits in the process. Whether the rising income will lift all or most individuals is yet to be seen and is another crucial matter for another column.

Comments can be sent to: tkhemraj@ncf.edu