When Graham Atkinson, of Santa Rosa, Moruca, dropped out of the government’s hinterland scholarship programme after the first term in second form at Central High School in Georgetown, it may not have looked like the likely start for a man who has worn many hats, including that of social activist, broadcaster and former deputy toshao.

“Obviously I was very sad and disappointed to leave school in Georgetown. I loved to read and there wasn’t a library in the village at a time. The school had limited books and the Roman Catholic church had set up a library sometime after. I missed the National Library where I used to go and read before going home,” Atkinson, 45, recalled.

After writing common entrance in 1987, Atkinson was awarded a place at Anna Regina Multilateral School on the Essequibo Coast and the government granted him a hinterland scholarship to attend school in Georgetown.

“My parents were skeptical of sending me on a scholarship in the care of guardians, maybe on account of other students’ experiences. In hindsight, maybe, I should’ve been sent to Anna Regina,” he said. In Georgetown, he was placed in an aunt’s care. At the end of his first year he gained 85 per cent in his grades and was in the process of being transferred to St Rose’s High when his aunt died and no new guardian was found to replace her. He stayed with his cousins and other family members.

“I was treated differently. I started to miss school and home chores increased. My schooling suffered. I tried telling some of the people in the hinterland welfare department but they did not pick up on it. My older brother, who was going into Moruca for the Christmas holidays, visited and I offloaded to him. He took me home. My father was angry that the authorities did not look into my situation satisfactorily. He wrote informing them that he wasn’t sending me back to school in Georgetown.”

Atkinson was placed in the secondary department of Santa Rosa Primary School, where his academic exposure at Central High served him well. “I wrote SSPE (Secondary Schools Proficiency Exami-nations) Part 1 and bettered Carolyn Rodrigues score. She had set a high score. I finished schooling at Santa Rosa Primary in Form Four after writing SSPE Part 2 and thought that was the end of my education and I would go into fishing, farming or the goldmines or do something like that.”

Santa Rosa Secondary School

Atkinson and his classmates were shedding the burdens of school life and getting into village life, like partying, travelling the sub-region to play cricket and such, when teachers, the late Victor Ferreira, and David James, who was just out of Cyril Potter College of Education, were canvassing parents and the community about setting up the Santa Rosa Secondary School.

“They spoke to our parents, unknown to us, and told them they saw potential in us doing well at the (CSEC) Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate. My parents told me they would like me to be in the first batch of students to write CXC as we called CSEC then. Without a moment’s hesitation I agreed to return to school. I used to cry to reap peanuts and peas. I returned to school at 15 plus.”

Atkinson and seven other boys and seven girls were placed in a class called Form Three Special and two years later they wrote four subjects, Mathematics, History, English and Integrated Science.

“It was a big event for villagers. It was the first time that a class was going to write CSEC in the village. They expected a lot from us. We had to perform with limited resources. Apart from teachers Vic and David, there were teachers Joe Torres, Justin Mendonca and two VSOs from England who shared their GCE O’ and A Levels (General Certificate of Education Ordinary and Advanced) experience.

The education department provided some textbooks. “We had six mathematics textbooks to be shared among 15 children. For a time everywhere we went as a group, to church, or market, villagers stopped us and wished us well. The community was involved. We felt loved. As a team, we would sit under the mango tree and help each other with assignments. We encouraged one another and studied under somebody’s gas lamp or we would we go home and use our jumbie lamps (flambeaus) as there was no electricity in the village at the time. When exams came around, they sent us home for one month to do revision. We were overconfident and my friends and I went fishing. We all did well as a group and we had set the bar very high for others to follow. I was one who got all four subjects with excellent grades.”

On leaving school, Atkinson took on a part-time assistant’s job to a researcher from Keele University. “I was in the fields in Region One-Barima/Waini when CSEC results came out. I got my results in late August. Teacher Vic encouraged me to seek higher education but there were distractions and attractions. My brothers and cousins were going to the gold bush and I was looking to go into the back-dams.

However, Santa Rosa Roman Catholic Church had started a Jesuit scholarship programme and being a top student, Atkinson was offered a two-year scholarship, from 1995 to 1997, at the Guyana School of Agriculture (GSA). “This was done behind my back. Dad was concerned about the direction I was taking. I came home a Tuesday afternoon and my bags were all packed. My mother looked very stern and dad said ‘You’re travelling tomorrow to go back to school.’ I was living in their house so I was shipped off to GSA to train in forestry agriculture.”

After that he explored the possibility of going to the University of Guyana but without support, the cost of living was prohibitive.

At GSA he was a volunteer-trained first aider and later found full-time employment with the Guyana Red Cross Society. He returned to Santa Rosa where he became involved with village and Moruca sub-regional matters, including education, information technology, infrastructural development and land titling issues.

“I interacted with John Atkinson, that great village toshao and other elders and learned about my community in a greater way. I was gainfully employed and contributing as a village councilor and representing the village at various forums in Georgetown including the National Toshaos Council. From 2002 to 2015, my life was basically working in the sub-region helping young people, mentoring some, helping at the schools with Health and Family Life Education as there was no one there to do it.”

In 2005, Atkinson was part of the crew that included teacher Victor Ferreira and former toshao Whanita Phillips that started the Moruca Expo activity. “We held successful expos throughout the years despite challenges of resources. We had communities coming together to showcase their culture, talent, skills, in food, dance and pageantry and in sports including archery and aquatics.”

He was involved in youth and sport development and was a member of the Moruca Youth and Sports Council that organised and promoted competitive sports with a focus on football, cricket and swimming. He helped to organise meets at the village and club levels and helped to form youth clubs while sharing information about healthy living. Clubs he helped to form included Silver Sands Club at Waramuri, Mariaba Sports Club, Mora Sports and Youth Group, Mighty Warriors at Kamawatta and West Rockers at Paloma.

Village Council

In 2015, Atkinson was the deputy toshao of the village council. “We had the Kumaka/San Jose bridge and Santa Rosa Village Mall project which we had lobbied government for. My task was to convince the then government that these are mega projects, by our standards, would benefit the community. We lumped the $1 million government gave to the communities to build the mall on the site of the old Moruca Producers Cooperative Society bond which was dismantled. It took two councils to finish it but we started it off.”

His time was also spent running behind the various government ministries and agencies to get work on the Kumaka/San Jose Bridge started. “They didn’t listen to us most of the time. They didn’t take our local knowledge on board, which has always been the case with governments and so you see the flooding on the dam. We told them about the need for a proper ramp and having the bridge extended.”

When his term as village councilor, which was a volunteer position, ended in 2018, Atkinson applied to fill to a vacancy advertised for a project coordinator for the Amerindian Peoples Association (APA) and was the successful applicant.

His father encouraged him to go after the job at the APA. “Working at the APA has consolidated my own belief about what we as Indigenous people need done in terms of the recognition of our rights, rights to land, to living our own way based on our own decisions and our right to be free from interference from whoever it be.”

His job gives him more scope to be involved in trying to ensure Indigenous People understand why they need to keep up the struggle for recognition and to be more integrated in mainstream Guyanese society. “Education has done quite a bit for us in terms of moving us forward and it has also helped in terms of ensuring that we hold onto our cultural traditions in a tangible way. It is heartening to see young people with their high school certificates holding on to their cultural traditions. It is giving us hope in moving forward,” he said.

From an early age Atkinson and his siblings were exposed to the guitar and music at home. His father played the Hawaiian guitar and he learned to play by watching him and his other siblings. “I performed in my first concert at age five or six at Santa Rosa Primary School. Since then I have played for concerts and accompanying groups at Moruca Expo. I now play the guitar for church and relaxation.”

In high school, he was also a part of the banchekeli group with village elders Hilda Phillips, Josepha Torres, Anthony Torres, Frank Hernandes, the Lucases from Parakese, among others, who taught them the traditional dances and songs. “I am one of those young old people who know most of them and I am willing to share with young people. Uncle Bull (Aloysius La Rose) was an inspiration to me to hold onto the banchikeli culture as a young child.”

It was not surprising to hear Atkinson on the airwaves. He always listened to news and music on radio and he loves to talk. “At GSA, I attended a training session for cricket commentators with sports journalist Joseph ‘Reds’ Perreira and Steve Bucknor and I was given the opportunity to do cricket commentary at a few live matches at Albion and Bourda. That was then. When I began to work with the APA, I was invited to give radio at the National Communications Network (NCN) a second chance. I went through a few crash courses and eventually they assigned me my own shift.”

Atkinson and Michael Abraham of the Rupununi were the first two coordinators of the Amerindian Heritage Sports games. They worked with then Minister of Amerindian Affairs Carolyn Rodrigues-Birkett to start the inaugural games. “We did that for a number of years with passion and purpose, initially for lunch money. From then to now the organisation has improved and the competition has gotten larger. Covid-19 has put a pause to things. We look forward to the games continuing. We have seen the fruits of our labour where our footballers are being spotted by clubs in the city. This is tied to our athletes furthering their education.”

The ‘co-op shop’

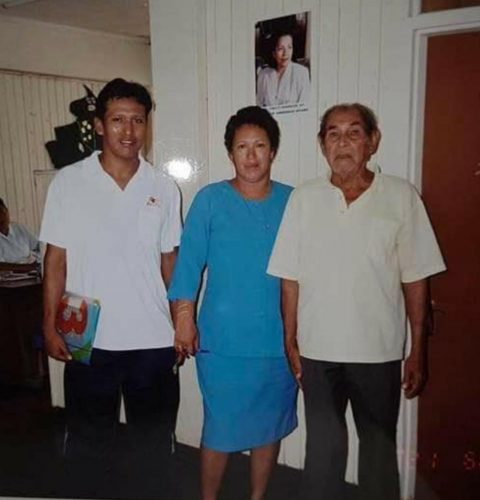

It is no surprise that Atkinson is an organiser and was among the village leaders in establishing the mall at Kumaka Landing. He supposedly inherited his organsing trait from his father and grandfather Bridges Atkinson, who pioneered the formation of the once famous ‘Co-op Shop’ at Cabucalli. Bridges Atkinson is said to have held one of the largest meeting of the village to sell them the idea of the co-op shop.

“Auntie Maxie Chappelle, her husband Uncle Mac, Auntie Beryl Rodrigues and her husband Uncle Joe, Gloria Jaime and a few other people were the main people behind the shop’s establishment. Grampa was overall manager and ensured there was transparency and accountability. Dividends were paid to shareholders. When I remember stuff from the late seventies and early eighties I remember the co-op shop being very vibrant. It really was a meeting point for a lot of folks. People came from as far as the Waini and Manawarin to sell their produce and to take back groceries to their families. The hunters and fisherfolk from Haimaracabra and Waramuri sold salted fish and meat. The craftsmen sold their matapees and sifters at competitive prices. Groceries, bread and fabric. It was a one-stop-shop,” he said, while noting that his father, who initially worked out of the community in the geology and mines sector doing surveying, settled as his family grew and managed the shop.