Emancipation as a concept and practice is not legally or morally tied to August 1st, 1838, the date of the formal removal of the institution of slavery in the British Empire after the Abolition Act of 1834 and the period of “Apprenticeship”. But ‘emancipation’, as Norman Cameron affirms in Evolution of the Negro, dates “back to the beginning of the slave trade.”

For its part, the memory of August 1st was perpetuated through oral history and more institutional forms of historical preservation. Two landmarks of emancipation were especially important: the 1888 jubilee of emancipation and the 1938 centenary.

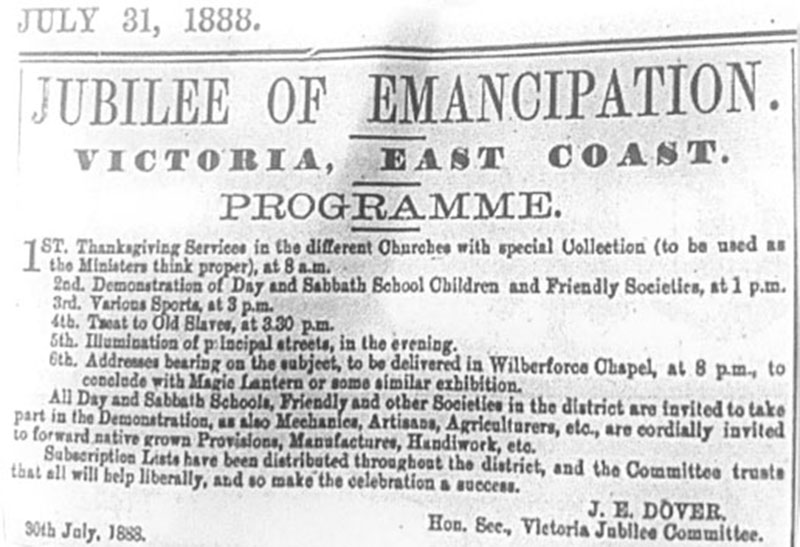

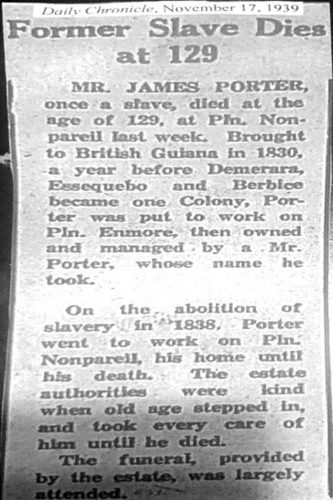

Emancipation Day in the 19th century was celebrated in myriad forms by African Guyanese including the ringing of church bells, sports events such as rope dancing, village bands, visits to the cemetery, recounting narratives of slavery, and feeding the elderly. In some cases, the estate would give out rum and sugar. In 1888, for example, the Daily Chronicle reported that in Victoria village “about 150 old slaves sat down to a sumptuous dinner in the Wilberforce church.”

In addition to moments of celebrations, African skills were present and flowered in many features of post-emancipation society: business ventures, mutual aid societies, gold and diamond mining, African art, ancestral language and dance retentions, and herbal use and traditional culture. Mellissa Ifill also researched the matrilineal “kinship structure” among African Guyanese in the post-emancipation period and its similarity to the Akan (the largest ethnic group in Ghana). Celebration is at once moment and memory of the formal dismantling of this brutal and inhuman system. Yet, in spite of the important symbolic legacy of August 1st, emancipation is a process with unfulfilled dimensions.

This article attempts to extract some aspects of the process of emancipation and the generally unexamined link between white supremacy, the British colonial order, and the social, economic, and psychological implications of repression and restrictions against African Guyanese as a community. Martin Carter’s evocative interpretation stands as one of the most striking statements on the power of the plantation complex: “And the more severe the downward pressure, the more intense was the lateral disturbance. This process has continued and is continuing so that we are witnessing a situation, where, as the downward vertical pressure continues intensified, we find the social, political and economic relations that attend this pressure serving to disrupt those arrangements that once functioned to obscure the essential reality…”

Process of Emancipation

Several issues emerge in the active understanding of ‘Emancipation’ from slavery in British Guiana (Guyana). These include a range of working concepts associated with the repercussions of the “downward pressure,” inclusive of: ambivalence (in responses to colonialism); internalized racism; resistance and accommodation; economic and legislative oppression; psychological attacks on being and living; intergenerational trauma; the ambiguous or contradictory role of religion (especially the dominant Christian religion); and collective determination or will formation.

Concurrently, Emancipation cannot be discussed in absentia of critical reflection of the challenges faced historically and contemporarily by African Guyanese on account of the global system girded and influenced by white supremacy. White supremacy in this is instance is understood or defined only in global context. The late Jamaican/Caribbean philosopher Charles Mills (of Racial Contract fame) puts it best: “White supremacy is the unnamed political system that has made the modern world what it is today…”. In short, a system that “continues to exist in a different form, no longer backed by law but maintained through inherited patterns of discrimination, exclusionary racial bonding, and differential white power deriving from consolidated economic privilege.”

Emancipation as a process in Guyana must also be seen in the context of regional and global events, such as the Morant Bay revolt in Jamaica in 1865; the American civil war and its aftermath, especially for African-Americans, the consequences of the European scramble for Africa in 1884-85; and the rise of scientific racism as an ideological construct with negative meaning and outcomes for people of African descent (and Asian and brown people) across the globe up to the present.

In Guyana, the post-emancipation era witnessed the rise of a vigorous press and correspondingly cautious colonial authorities attempting to limit ‘press freedom’, as modest and formative as the concept was at the time. The enlargement of the African and colored middle class later in the 19th century brought new professionals into competition with whites and with each other. Inclusive of civil servants, teachers, and other professionals, the middle-class representatives were distinctive by their education and adoption of English cultural values, and by extension the quest for ‘citizenship.’ These black and colored pressmen and civil servants confirmed a kind of “contradictory consciousness” in the colonial Caribbean. That is to say, on the one hand they possessed a sense of themselves as citizens with all the cultural and social paraphernalia, while on the other they endured continued restriction from positions of power, prestige, and recognition, and obliquely or directly were refused entry into white spaces. Thus, the phrase “resistance and accommodation” (Walter Rodney) is still the paramount descriptive of the African Guyanese response (as well as the other ethnic groups vis-à-vis the colonial order).

The petition sent to Queen Victoria in May 1842 must have been one of the first formal post-emancipation shots at reparations for the time. It was signed by George McFarlane, President of the Guiana African Association, and listed a whole series of complaints and calls for redress of “vexations which are secretly accumulating over the heads of the coloured people, which have forced them to combine for their mutual protection.”

Additionally, in 1842, the first organized press opinion formulated by African-Guyanese was unsheathed with the launching of the Freeman Sentinel – the organ of British Guiana African Association at the time. The Freeman Sentinel, it was claimed, had “encouraged the ex-slaves to build and unite the family and to fulfill their duties to the African community.” The Governor of the time accused the newspaper of “false representations, reckless of truth and justice and exciting discontent in the masses.” Under such pressure, the Freeman Sentinel soon collapsed.

However, the “non-traditional”

press did not perish with the Freeman Sentinel, and it was to be followed by several other newspapers, into the twentieth century, that represented African-Guyanese

White supremacy and its local hirelings found ways to upend any progress made from 1838. The first salvoes were aimed at restricting and suppressing the village movement, but there were many others. The reduction of wages of African Guianese workers in the 1840s resulted in strikes and disturbances. To add insult to injury, an 1864 ordinance denied women entry in the governing Court of Policy. This restriction on women might have partly stemmed from the unrest and the lively participation of African Guyanese women in the unrest of 1856 (Angel Gabriel) and after. There were also drainage and irrigation issues; restriction on crown lands for African Guyanese, and unfair and malicious taxation. Among the issues of contention at a later stage was the locally inspired (so-called imperial Colonisation Deputation of British Guiana) planning for the Indian Colonisation scheme and funds accorded to indentureship and immigration.

Brian Moore authoritatively argues that disempowering African Guyanese at the village and state levels was an organised effort by the white ruling class in the colony in the post-emancipation period. He is unequivocal: “the most pervading problem that Creoles of all classes continuously faced in post-emancipation Guyana was White racism.” In sum, white supremacy, which unfortunately would be picked up, dusted off, and used by other ethnic groups, and even by some African Guyanese. In other terms, internalized racism. This tacit acceptance of the “Western” codes and behaviour and response to inequality is highlighted by the description of the black political leader Joseph Eleazer. Accordingly, Eleazer wanted no part of “African”, declaring he “was no African but came from British Guiana and thereby had no other loyalty but to British civilisation.”

The evidence of White Supremacy in Colonial Guyana

In spite of gains made by African Guyanese in post-emancipation Guyana, the steady hand of racial prejudice was consistent. Racism in the colony expressed itself openly and covertly and Guyanese history is rich with African condemnation of this situation at the economic, political, sociological, and psychological levels.

Before and after the 1905 Georgetown riots, the Creole newspaper and black citizens of Guyana had cause to consistently critique the conduct of Governor Frederick Hodgson. It became so testy between the Governor and the populace that the Creole ran a disapproving column for weeks titled “The Hodgson Administration.” The roots of the resentment not only extended to Hodgson’s attitude to the riot and his prosecution of the rebellion, but also to issues like land and an open conflict with the popular politician Patrick Dargan. The Creole deemed the governor “a negrophobist of the most aggressive type” and a man “so persistent in his declarations against the Negro; so prone to vilify them, and so eager to find out and publish their faults and even their foibles.” In another issue, the Creole produced a related column, “White Lies about Black People”.

The British-born Guyanese historian and botanist James Rodway (author of Story of Georgetown) pursued an openly racist line in an August 1913 lecture entitled, “Slavery – Its Evils and Benefits.” Rodway affirmed the classic racist tropes in stating: “Physically the black man is strong and powerful…mentally he must be considered deficient; his great want is inventive genius. He has never displayed ingenuity in art or literature…” Rodway was immediately supported by the conservative Daily Argosy, but directly confronted by the Afro-Improvement Association of British Guiana and its secretary Joseph Conway. Conway provided a long list of local and global African achievement while challenging Rodway to “jot down” his racist theory “between two covers, and our Association will find it (sic) most congenial exercise to teach you that the negro whom you so decry is the off shoot of a stem once luxuriant in the fruits of literature and art, while that from his Gothic ancestors have spring were hard knotted and barbarous.”

Subsequently, groups like the BG Political Association and the Negro Progress Convention began to publicly challenge views like the one professed by Rodway. But one social historian contends that while “the attitude of the Afro-Guyanese masses, from the record available, was healthy and progressive and that their role was extremely creative, at the level of the colonial assemblies, the role of African Guyanese was not as singularly distinguished.” As per Lutchman’s contention, the radicalism of African-Guyanese “came and went” and that “‘love of promotion’ and love of being honoured eventually overcame the radicalism of middle-class politicians.” Linked to this, perhaps, is another fact offered by Lutchman, that the function and content of education was largely left to Christian religious bodies until the first Government administered school was inaugurated in the 1920s.

A confidential memo from the desk of Sir Walter Egerton, Governor of British Guiana from 1912-1917, is another classic example, and a clear manifestation of the covert racism of the British colonial class. It is worth a full reproduction:

GOVERNMENT HOUSE

Confidential

Georgetown, Demerara

11th March 1914

Sir, With reference to my dispatch No.75 of even date, I have the honour to state that Mr L R Sharples, who is referred to therein, is of African descent, and in view of this fact, as it is inevitable that a Government Medical Officer should in this Colony during his career be stationed from time to time in districts where he is the only medical practitioner, and as white patients object to being treated by a medical Officer who is not of their own race, I cannot recommend the appointment of Mr Sharples.

I have the honour to be

Your most obedient humble servant,

Walter Egerton

Then there is the case of Governor Graeme Thomson. As Harold Lutchman recounts, the said governor had issued instructions in 1925 (very similar to Jim Crow legislation in the USA) to the effect that “no film is to be exhibited in which there is the least suggestion of intimacy between men of Negro race and white women…” The Governor’s intent was to not bring “the white race into derision…or disrespect.”

These examples are only the cusp of the racism borne by African-Guyanese all the way up to modern times. That racism and ignorance extends to the still negative depictions of the African continent and all the stereotypes accorded Africans in the diaspora that has maintained consistency from enslavement to the present.

On August 1, 1930, the Rev. S.E Churchstone, in commemoration of Emancipation Day, wrote the following in the Daily Chronicle:

“I do not regard the emancipation of the Negro as an ‘experiment’ which needs to be guarded against hurtful eventualities; nor should the struggle of race and class for economic comforts, be allowed to lower the worth of Negro effort and character. Participation in the everyday productions and privileges of things necessary to human well-being is the legitimate offspring of emancipation. The Negro in British Guiana, therefore, is destined, under equitable governing laws, to be a participating, cooperative factor in the commercial, political and industrial regeneration of the Commonwealth.”

Churchstone’s statement is a thought-provoking evaluation of the problem of African Guyanese freedom past and present. While just a fragment of his overall message, he hints at the tendency to relegate freedom and citizenship to economic comforts alone at the expense of political, social, and cultural integrity, a sentiment that holds echoes into the present time. Relatedly, there can never be full emancipation without reparations.

Nigel Westmaas is an Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Hamilton College in the United States.