Finding that the President had meaningfully consulted the Leader of the Opposition, acting Chief Justice Roxane George SC has affirmed the appointments of the Chairpersons of both the Police Service Commission and the Integrity Commission.

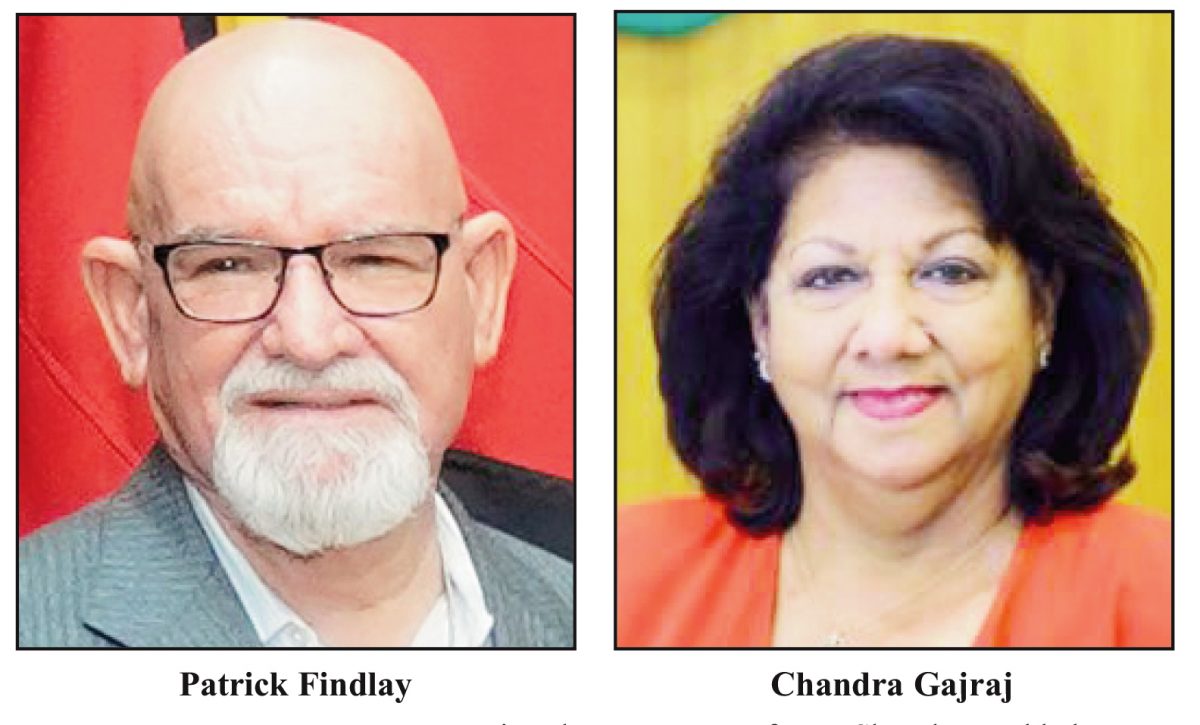

In her two-part ruling, delivered yesterday afternoon, Justice George also validated the appointment of the members of the Integrity Commission but while upholding Patrick Findlay’s appointment as Chairman of the Police Service Commission, she was keen to distinguish it from that of the appointment of the body itself, which she said was not lawfully reconstituted.

On the latter point, Justice George found that President Irfaan Ali had sufficiently discharged his duty to meaningfully consult with Opposition Leader Aubrey Norton but added that in the absence of a Chairman of the Public Service Commission, which was integral to the process of consultation needed for the reconstitution of the Police Service Commission, that body was not legally set up.

It had been Norton’s contention that the President failed to “meaningfully consult” him as is required by law, before appointing Findlay and Chairperson of the Integrity Commission Chandra Gajraj.

Regarding the requirement for procedural fairness in the process of meaningful consultation, Justice George noted that the President’s consultation with Norton bore the elements of dialogue, inclusion, mutuality and accommodation as established in case law.

She then added transparency and accountability.

Justice George said that contrary to Norton’s arguments, and having regarding to the various correspondences and meeting between the President and him, he was sufficiently provided grounds/reasons for the various appointments complained about.

On this point, the Judge ruled that as is constitutionally required, there was communication in writing between Norton and the President, regarding, among other things, what the consultation was about.

She noted Norton’s request for the CVs of the persons under consideration being met by the President with a date which was also set for a follow-up in-person meeting between them.

Without merit

The Judge pointed out that while Norton complains, he never explained in his affidavit apart from the CVs, what it was that he required and still requires by stating that he wanted “all information and materials” to aid him in forming a considered opinion on the nominees put forward by the President.

Citing Norton’s complaint through his attorney, Roysdale Forde SC, that reasons had not been given by the president for the nominees he identified and that CVs alone were inadequate, Justice George said that reasons were in fact provided.

Referencing correspondence on behalf of the President from Minister of Parliamentary Affairs and Governance, Gail Teixeira, the Chief Justice said the reason given was that the persons named were “people of good standing” and that Norton was also familiar with those names.

In addition, she noted that it was highlighted that Findlay was one of four persons approved by the National Assembly for appointment to the Police Service Commission.

Against this background, she said that the unanimous approval of the members of the Police Service Commission by the National Assembly, in addition to the CVs provided in her view, represented sufficient information and reasons for the appointment of Findlay, Gajraj and the other members of the Integrity Commission; and further for Norton to have given an opinion about them.

Moreover, the Judge said that regarding the nominees for the Integrity Commission, Section 3 (2)(3) of the Integrity Commission Act provide for the professional criteria of nominees, while stating that Norton could have examined whether they met the requirement and made a contribution in that regard.

The Judge said that she was unclear, and Forde seemed also unable to assist her as to what other grounds or reasons could have been provided for nominating the persons beyond what was submitted.

Against that background, Justice George concluded that Norton’s contention of not being provided sufficient information was without merit.

Further, regarding Findlay’s appointment, she said that while the appointment process for the members of the Police Service Commission by the National Assembly is separate from that of the Chairman of that Commission by the President, the fact remains that it is via a bi-partisan committee involving the members of the National Assembly, which agreed that Findlay be recommended for approval by the National Assembly.

On this point the Judge said that Norton must have understood that pursuant to Article 210 of the Constitution, nominations for the chairmanship were restricted to the four members who had been approved by the Committee of Appointments of the National Assembly.

Justice George noted that in that regard, Norton as a Member of Parliament and Leader of the Opposition, would have participated in the process which confirmed the committee’s nominees, which thereby unanimously approved Findlay’s appointment to the Police Service Commission and that he ought to have appreciated that Findlay could have then been appointed by the President to be Chairman.

Citing case law, the Judge said that Norton would be taken to know the effect of that parliamentary exercise of which he would have been apart as a member of the National Assembly.

This had specifically been the argument advanced by counsel for Findlay, Darshan Ramdhai QC.

In the final analysis, the Chief Justice said that Norton was presented with enough time to communicate his objection to any of the nominees who were eventually appointed.

The Judge referred to his complaint of Findlay being politically partisan, and cited that while that was not a consideration for the Court, it certainly would have embodied an objection of his. The Judge reiterated, however, that while Norton asked for additional grounds and reasons behind the persons nominated, he never said what he further required, nor said what his objections were, or even proposed recommendations of his own.

She noted, too, that even though an opportunity was given him to communicate to the President what further grounds he wished, this was never done.

The Chief Justice said that Norton ultimately refused to engage and that the President’s decision to proceed with the appointments was not unilateral and that the President had discharged his constitutional duty.

Not properly constituted

Regarding the appointment of the Police Service Commission and whether it was lawful, the Chief Justice said that there needed to be the determination as to whether the chairman of this commission, properly engaged in consultation with other members of the Commission, as a precursor to the president then engaging in meaningful consultation with him in relation to the appointment of an acting Commissioner of Police.

It was Norton’s contention that the Police Service Commission was not constituted in accordance with Article 210 of the Constitution, since subsection (1) had not been complied with, since the Chairman of the Public Service Commission is not yet a member of the Police Service Commission.

On this point, Norton argued that Findlay could therefore not have lawfully engaged in any consultation with any other members of the Police Service Commission, as is required by Article 211 (1), since the Chairman of the Public Service Commission has not been appointed and is required by the Constitution to be a member of the Police Service Commission.

The Judge said that the Constitution requires the Chairman of the Public Service Commission to be a member of the Police Service Commission.

She said that there is no dispute that the Chairman or the Public Service Commission has not been appointed to the Police Service Commission and noted Forde’s submission that in order for this commission to be properly constituted the Chairman of the Public Service Commission must have been a member and that is he or she must have taken the oath of office to serve on the Police Service Commission.

Contrary to arguments advanced by Attorney General Anil Nandlall SC on behalf of the State, the Chief Justice said that in this case in this case, it is not the Commission that is performing one of its functions, but rather the Chairman performing a specific constitutional function, which is exercised after consulting with other members of the Commission.

On this point she said, too, that as opposed to Nandlall’s argument, the failure to appoint a member could not be considered to be a vacancy.

The Chief Justice said the law was clear that for the Police Service Commission to be properly constituted the Chairman of the Public Service Commission must be a member; while adding that it cannot be that the framers of the Constitution would countenance a situation where, from the inception, a member is not appointed, but the issue would be deemed to be constituted.

“My conclusion is that in the absence of the Chairman of the Public Service Commission, this Police Service Commission was not properly constituted,” the Chief Justice said.

Given her ruling, however, and the fact that the rights of third persons who are not parties to the proceedings for an audience before the Court, Justice George saved the promotions of ranks which were made by the Commission.

The three other members appointed to the Police Service Commission were Mark Conway, Hakeem Mohamed and Ernesto Choo-a-Fat.

By way of a fixed date application (FDA), Norton had argued that the President appointed Findlay as Chairman of the PSC without first meaningfully consulting him as is required by Article 210 (1) (a) of the Constitution.

Further, he said that President Ali also appointed Gajraj as Chair of the Integrity Commission without meaningfully consulting him in accordance with Section 3 (4) of the Integrity Commission Act.

Norton was arguing that the appointments are “illegal, null, void and of no legal effect” and wanted the Court to so declare.

He also wanted the Court to declare that the appointments of Dr. Kim Kyte-Thomas, Imaam Mohamed Ispahani Haniff, Pandit Hardesh Tewari and Reverend Wayne Bowman as members of the Integrity Commission were done without proper consultation and are therefore illegal.