Researcher in the Department of Language and Cultural Studies, University of Guyana, Louisa Daggers wants legal protection for cultural sites and cultural heritage.

Daggers, 35, notes that Guyana has neither accepted nor ratified the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property.

“So it is on us as a people to protect our cultural sites and cultural properties. This is why we hope our recent publication, The Archeology of Guyana, can bring some awareness to people and communities. Once you sell that bit of your cultural heritage, there is no way to get it back. Hopefully with greater consciousness of how important this heritage is, we can collectively, as a country, work with our governments to have proper policies in place to protect heritage sites given the rapid rate of development, mining, logging and risks from climate change.”

Noting that the protection of sites will be a long process with challenges, she said, “Archeology allows us to give voice to the past, to the heritage that exist and to advocate for the conservation of sites for future generations. These sites can help us understand the challenges of the past. We can use the data we are collecting to help us make better decisions, especially when we talk about climate change for example.”

Daggers recently told Stabroek Weekend that very little is known about the Mazaruni area, where gold is mined. Miners and people in general find artefacts and sell them directly to people who establish themselves as collectors.

“We want people not to sell or to buy artefacts. Oftentimes that is the conflict with heritage management and archeology.”

With October month being International Archeology Month, the PhD student said, UG’s Department of Anthropology has activities planned, including three lectures and field trips in the Rupununi.

Born in Georgetown, Daggers attended both nursery and primary schools in Mon Repos where she spent most of her life and obtained her secondary education at the then International Business College (IBC) in Georgetown.

Her father, a retired teacher, encouraged his children to read. They spent a lot of time at the National Museum, the National Library and looking at National Geographic documentaries on television which inspired her love for the heritage and archeological fields.

She was happy to reunite with one of her IBC teachers Aaron Lennox, her first Indigenous teacher, at a National Toshaos Council Conference, who told her she would do well in history and tourism. “I kept that with me.”

Passion ignited

Just out of high school, she pursued a bachelor’s degree in tourism at the University of Guyana (UG) which gave her the chance to travel, to experience life in Indigenous communities and introduced her to cultural heritage.

While at UG, she spent a few August holidays with a friend from Pakuri, going to the farms and listening to the elders speaking about their culture.

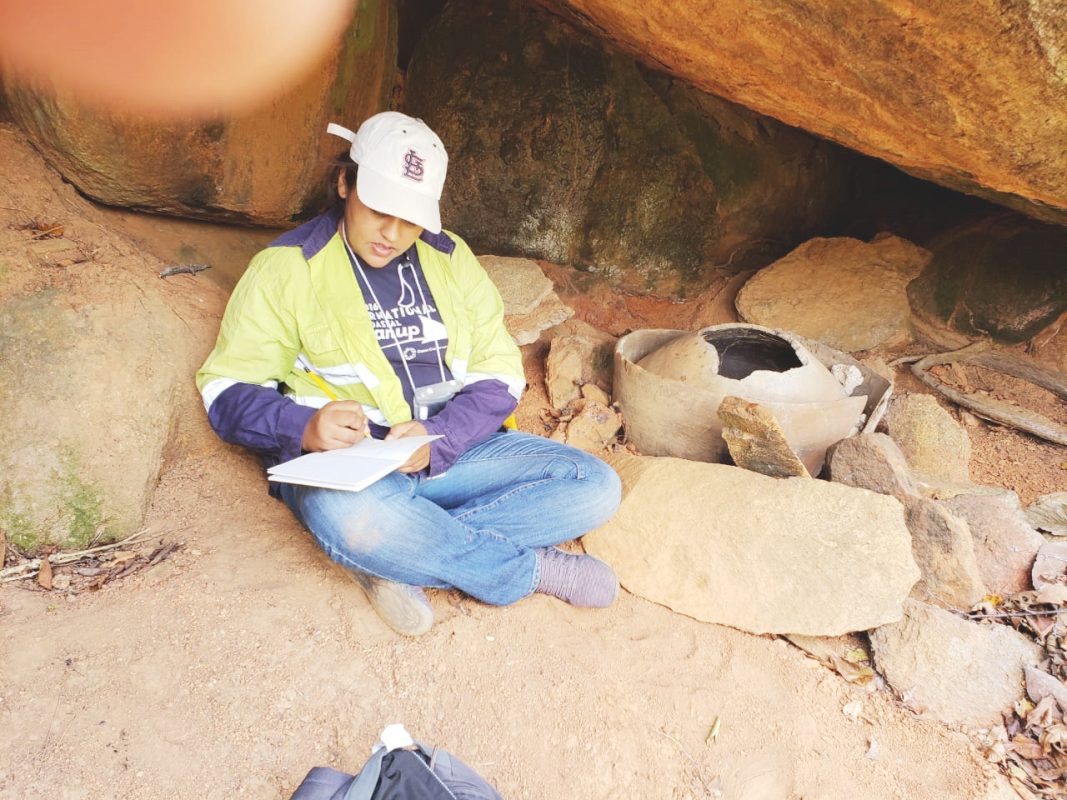

“That is where my passion for working with Indigenous communities, archeology and everything came to life.” At UG she met archeologist/artist, the late Dr George Simon, one of her lecturers in the course Introduction to Indigenous Peoples of Guyana, which focused on the archeology component. Simon was attached to the Walter Roth Museum (WRM) through the Dennis Williams Archeology Field School which built students’ capacity in archeological field techniques.

Simon encouraged her to join the field school in her first year. The field school was a collaborative effort between WRM, UG and Boise State University (BSU). Dr Mark Plew, a professor at BSU, conducts the archeology programme in the Department of Anthropology at UG.

Two weeks after Daggers first experience in the fields at Errol’s Landing in the Fairview area in Iwokrama, WRM had a vacancy. There were three candidates for the position and all three were employed. Daggers was placed at the National Museum, while the others were placed at the Museum of African Heritage and WRM. A year later, by which time she wanted to work with museums, she obtained a transfer to WRM, where spent much of her time doing collections management and was introduced to the work of previous curators which allowed her to do more field work.

For her final year project, she looked at their economic viability in the tourism industry, how they could generate tourist dollars and boost museums policies.

She did the field school in 2007, 2008 and 2009. “Eventually I was co-supervising the field school with Dr Plew. I was doing the theoretical part and both of us going into the fields.”

From her first experience, the field school’s programme is now conducted over a six-week period. “For a beginner I didn’t think meeting two times over three weeks initially was enough. We have better access to technology, more literature, simulation of sites, more videos and how to use the GPS. So we send students out with a little bit more confidence than when I started.”

In 2011, the year after she obtained her bachelor’s degree, Daggers was recommended as a candidate for a full one-year scholarship to pursue a two-year master degree programme in archeology at BSU but Daggers was not confident because of her background in tourism.

Plew assured her and sent her a box of books that an undergraduate student in archeology would read. After reading and gaining some confidence, she applied for entry to the programme, gained acceptance and BSU approved the scholarship.

In July 2011 two days after the field school did their first excavation of Siriki shell middens in the Pomeroon River, she was off to BSU.

With one-year funding for the programme, Daggers decided to double up on the courses. She did seven and eight courses when some students were doing three and four and completed the programme with a 4.0 GPA score.

In Idaho, she also supervised Plew’s field school with his undergraduate students while doing a handwritten thesis.

“When the programme was coming to an end, Plew suggested that I apply for a job in the US and gain some experience. Great as it sounded, I said, ‘Sorry Dr Plew. I’m waiting for the first flight back to Guyana.’”

Before returning, Daggers, who had resigned from her position at WRM because she was not given a leave of absence, reapplied for her job.

“I was excited, driven. I was returning with a masters in anthropology and archeology and I thought I was going to revolutionise the world of museums in Guyana. After a year I realised I was the only person who was driven. I sent proposals about the 95,000-hectare Berbice site, a huge complex of prehistoric mounds which was under the spotlight because it included Ebini that stretches to Torani Canal, Dubulay ranch, Abary Savannah and Fort Nassau Savannah. I was passionate about the protection of this site. During that time, I learnt lands were being given out for agriculture and other developments. I saw some of the environmental impact assessments and learned the developments would fall within the area of these archeological sites. I wrote proposals to the ministry for rapid assessments. I felt we could have pulled the resources together and even if we could not protect all of it, we could have found a part of it that was representative of the sites for protection. At the time we were busy with the ministry trying to convince them there was need for a cultural and an archeological policy because we have nothing that governs archeology and how archeological sites are managed. We still need a comprehensive policy that is specific to archeology.”

Collections management

Daggers knew that Wishart and Gerard Pereira of the WRM had spent a considerable amount of time and resources trying to get the collections in order so she also worked voluntarily on weekends to improve collection management and building the database.

“One year later, I realised we were asking for a freezer to preserve some of the artefacts that could have been infected with fungi and termites. Two years later, we still couldn’t get a freezer. The ministry was refurbishing other parts of the museum with fancy furniture and we couldn’t get a freezer to care the very thing that was going to keep the museum in existence. We went back and forth with the ministry on collections management till I just couldn’t do it anymore.”

She had joined WRM in 2012, was paid on a month-to-month basis and then on a temporary contract without the benefits of leave or gratuity. Initially she had wanted to apply for the post of director of archeology, which the late Dr Dennis Williams held, but she was told the position no longer existed.

She resigned in 2014 and joined the staff at the Amerindian Research Unit at UG as a researcher.

The university provided her with opportunities for research and engagement with communities which was limited in her previous position.

The year 2022, she said, “Was a real eye opener. I spent time in South Rupununi doing work with the South Rupununi District Council and dialoguing with rangers and elders. I suggested to Dr Plew that we may need to go back to the drawing board and how we look at the archeology of Guyana. The feedback from the people in the Rupununi showed there was enough ethnographic work done in the communities to understand the dynamics of culture and how culture evolves from an archeological standpoint.”

The university also allows Daggers to engage the younger folks who are enthusiastic about archeological heritage and do not know where to begin to build their capacity in field work. “They collect data and we help them in interpreting and making reports. The idea is to empower communities and to help with the preservation of sites. This will help them better understand their culture, identity and place in society which is important if they are going to talk about advocacy for human rights, indigeneity, self-determination and everything else.”

She said it was important people understand the cultural dynamics of the landscape of their ancestors and preserving that heritage. “We are trying all the conservation approaches. We are also responding to loss by obtaining tangible records of what was there.”

Shell mining

Daggers and a colleague from the Kanuku Mountains Communities Representative Group are to make a presentation at a conference on the vulnerability of the Caribbean and climate change in Aruba in November. “We are approaching it from an archeological and a traditional knowledge perspective, what the archeological record is saying about climate change and how we can use that collectively to inform the present and future.”

For the 14 or 15 years she has worked with Plew, she said their efforts were on the north western shores’ middens of Regions One and Two where they looked at how people adapted to changes. While the shell mounds are a wonderful archive of pre-historic information, she said, “Unfortunately, there is not a lot of emphasis on conservation by the authorities so many of them are not well preserved. Some people fill their yards with the shell middens.”

Daggers noted the Wyva Creek shell midden in the Barama River, which was a huge mound, has been completely mined out. I was only able to collect data from a part of it.”

The shell midden is an accumulation of diet and burial records which also gives an insight into tools used at the time.

Of the human remains excavated by Williams from Barabina (Region One) and Pyraka (St Monica) shell middens, Daggers said, “We have been looking at that for the last 13 or 14 years and have found they are a great archive for environmental data, climate data and human adaptation. We gathered that prehistoric people would have experienced multiple episodes of climate change. We are now going to use that record and try to bridge the gap between traditional knowledge and archeology.”

Second edition, Archeology of Guyana

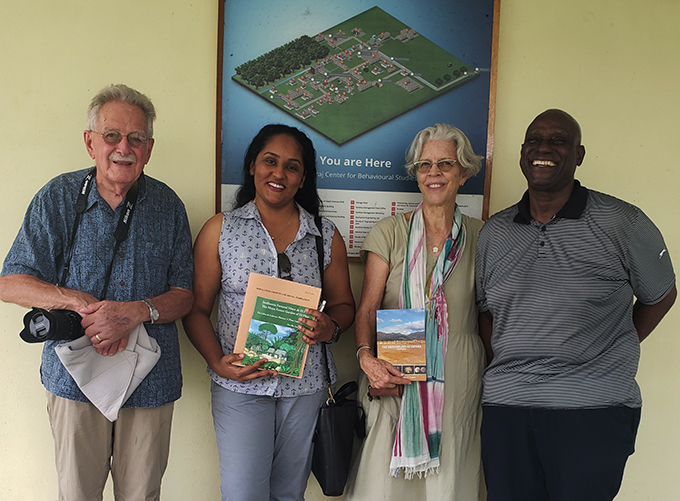

Daggers co-authored the second edition of The Archeology of Guyana with Plew, who authored the first edition in 2005.

In 2015, UG had funding from the World Bank for research to inform policy under the UG STS (Science, Technology and Society) project.

She convinced Plew to apply for the US$50,000 grant to look at low carbon environment using the archeological record to see if prehistoric populations had any role in climate change.

The application was successful and the grant allowed them to go back to Siriki to continue the excavations they had begun in 2011, to explore Little Canaballi in Barama which was never excavated before and to return to Wyva Creek to supplement the data they had.

They pulled Williams’ Barabina, Pyraka and the Waramuri collections, which were much larger collections than they have today and set benchmarks for analysis to see what they would uncover.

“We sampled so much of the stuff, we had a lot of findings we didn’t expect. We were also able to deduce that the people moved sediments from one place to the next and that 7,000 or 8,000 years ago they fired the landscape for hunting and farming in the same way it is still being done in the Rupununi.”

For the project, Daggers did the data analysis in Idaho in October, 2016, when she also learned to prepare samples and work with experts in isotopes about what the results were saying. That was when Plew said he was thinking about publishing a second edition to the Archeology of Guyana and he wanted Daggers to co-author it. She agreed.

When approached, even though the manuscript was good, the UG Press was not sure it would sell because it was about archeology, not a popular subject. When Professor Dr Paloma Mohamed took over the vice chancellorship, Daggers wrote to her about the issue and she responded favourably. The book was launched in August.

“It was a proud moment for us knowing that UG Press is the home of The Archeology of Guyana (Second Edition). The response to it has been good.”