On August 19, the Stabroek News reported that the government is willing to make necessary interventions in the foreign exchange (FX) market in order to enable the smooth access to hard currencies. In the same news report, Vice President Jagdeo noted that there is ample foreign exchange if one considers the total amount available to the market. The Vice President further noted that the reason why some folks have to queue up for foreign currency has to do with the dysfunction in the local interbank market.

I have no reason to doubt the explanation of temporary or localized shortages. I have long written about foreign exchange frictions or constraints, causing temporary shortages, in the FX market that I first estimated around 2005-06 when I was conducting my graduate studies in New York City. Any market characterized by frictions is not working as well as it should. I found that banks in Trinidad and Tobago and Guyana often place customers in a queue, resulting in a period of waiting (a foreign exchange constraint). The constraint has implications for bank portfolio adjustments in terms of their investment in loans, Treasury bills, foreign assets, and excess reserves.

What is important, however, is these temporary shortages are still happening in an era when Guyana is receiving its greatest inflow of foreign investments and natural resource rents. As at end of July 2023, the Natural Resource Fund had a closing balance of US$1.859 billion and the Bank of Guyana’s net international reserves settled at US$695.6 million. The latter was down from this year’s highest point of US$807.4 million in February.

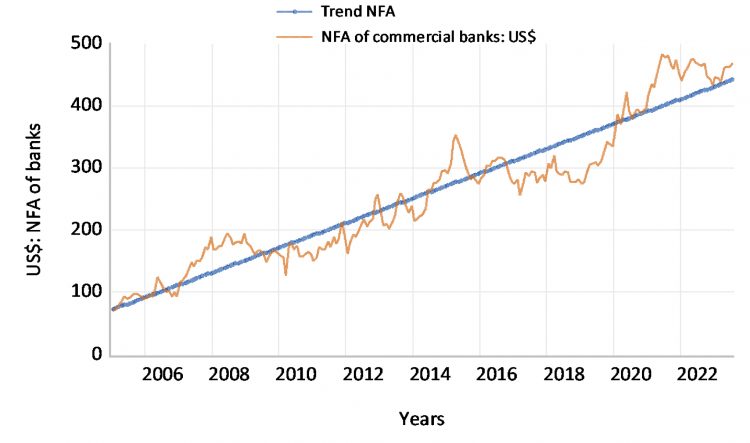

In the aggregate, as noted by the Vice President, the commercial banks continue to experience a rising level of net foreign assets (NFAs), which ought to be available for meeting the private sector’s demand for foreign currency. The first chart presented in this article indicates the trend in commercial banks’ NFAs from January 2005 to July 2023. It is clear that the commercial banks’ NFA is trending upwards, amounting to US$466.5 million at the time the data was last released: end of July 2023.

From October 2016 to December 2019, the level of banks’ NFA dropped below the trend line. However, starting from December 2020 until the last reported data, the banks’ NFA exceeds or overshoots the trend line, indicating that in the aggregate there is an increasing level of foreign exchange assets held by the banks.

The aggregate NFA of the commercial banks does not tell the entire picture, however. We have to delve into the three main categories that are reported by the Bank of Guyana: (i) balances due from banks abroad, (ii) loans to non-residents and (iii) other.

Interestingly, the category classified as “other” is the largest. I find it strange that the largest segment of banks’ foreign assets is not more precisely defined and explained. It likely includes the more illiquid overseas investments of commercial banks that are not immediately available to Guyanese importers who urgently need hard currency. These are likely investments tied up in time deposits in counterpart banks. As many savers know, a higher interest rate can be earned by depositing funds for several months in time deposits. Breaking a time deposit can fetch stiff financial penalty.

Loans to non-residents form the smallest share of banks’ foreign assets. At the end of July, the banking system loaned out US$40.2 million to non-residents (accumulated level). It is not clear in which currency these loans were made. Were the loans priced in Guyana dollars or US dollars? Were these loans used for establishing new factories and physical assets? Or were they used to purchase foreign currency for remitting overseas? Loans to non-residents are on the increase since October of 2022, reaching a high point of US$43.2 million in January of 2023. Certainly, an expansion of credit for purchasing foreign exchange could add extra strain in the market and account for some of the temporary shortages that have been reported.

However, the most revealing sub-category is the one known as “balances due from banks abroad”. As everyone knows, a Guyanese bank must work with a foreign counterparty bank. For example, if someone purchases a manager’s cheque for US$100,000 that fund will be drawn on an account at Bank of America, Chase, Bank of New York Mellon or some other key bank based in the US. It means that a local bank must maintain a sufficient amount of hard currency in its counterpart bank so that the Guyanese customer can access the US$100,000.

Balances due from abroad have to be the most liquid component of commercial banks’ net foreign assets. It must be available on demand to clear cheques written by banks inside Guyana. Observing the pattern of this category will provide insights into why there has been a recurring claim by some local businesses that they cannot easily obtain foreign exchange.

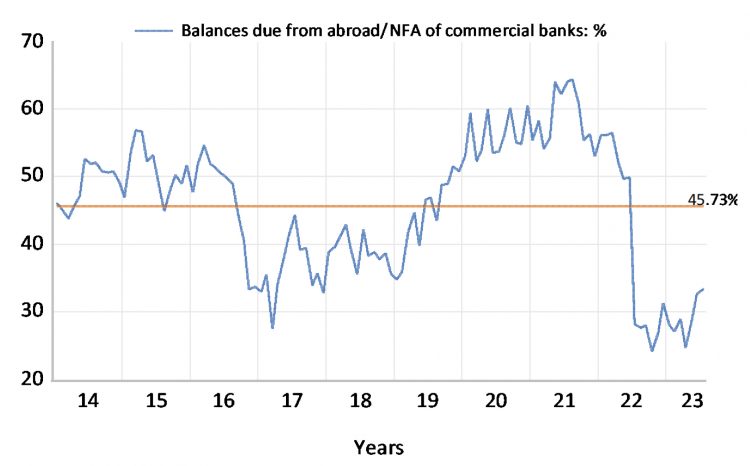

This pattern is illustrated in the next chart, which presents the percentage share of balances due from abroad relative to the total NFA of the banks. The flat line shows the average of 45.73% over the period January 2014 to July 2023. From September 2016 to June 2019, the percentage undershoots the average of 45.73%, reaching a low point of 27% in March 2017. This means that in the said month only 27% of banks’ NFA was available for imports and other uses of foreign currency. Over this period of the Granger administration, there were also several claims of foreign exchange shortage. In the same month of March 2017, the BoG’s net international reserves were strained and amounted to $596.3 million. However, the level of imports in 2017 was substantially smaller than what it is today. Guyana’s total imports were US$1.6 billion and US$3.6 billion in 2017 and 2022, respectively.

Since June 2022, the percentage of balances due from abroad plummeted significantly below the long-term average reaching its nadir of 24% in October 2022. This is the period over which the claims of FX shortages are much more pronounced. As noted in the previous chart, the total NFA has increased consistently; but the second chart shows that the liquid amount available for greasing commerce fell significantly. One possible factor explaining this outcome could be a breakdown in inventory management by the banks. Or the banks might be more willing to engage in proprietary investments than serving customers. Having said that, this anomaly in a period of oil boom needs further examination and deeper research.

Meanwhile, since January 2022, the Bank of Guyana has purchased US$114.4 million dollars from the domestic market while it sold US$48 million, giving a net purchase of US$66.4 million. This policy may seem counterintuitive given the temporary shortages reported over the past year. Perhaps the BoG was under pressure to maintain a safe level of import cover given the noticeable decline in its reserves from January to July of this year.

Capital loss would have accounted for why the BoG’s foreign reserves fell. As interest rates increase, the market value of outstanding US treasury bonds and bond ETFs would have declined. This is a short-term hiccup as I expect these assets to recover when interest rates in the US start to move downward.

Comments: tkhemraj@ncf.edu