From selling corilla bush for tea in England 25 years ago, founder of Dalgety Teas, Mark Dalgety, 57, now has 36 lines of herbal teas, some eight families of teas, all sold in cities in the United Kingdom, United States of America, Nigeria and in some Asian markets as he continues to expands his business globally.

Dalgety Teas, which moved from one-ounce packets to tea bags and then to instant tea, was recently one of five winners of £100,000 worth of free advertising on the UK’s Channel 4 in a ‘Black in Business’ competition. Over 1,000 entries were submitted. Channel 4 is one of the UK’s largest TV stations with over 49 million viewers.

“The adverts will allow us to move our products in the UK’s mainstream markets. We’re coming up in direct competition with major players like Liptons or Typhoo Tea that are spending millions of pounds sterling on major marketing on television. This opportunity is, probably, one of the best things that has happened to us in 25 years,” Dalgety told Stabroek Weekend.

In Guyana at present, Dalgety is scheduled to travel to London, England during the course of this month to do filming for the advertisements.

In 2008, Dalgety Teas won the Thames Gateway International Business Award for selling herbal tea to China.

“It was the only company in the early 2000s to export something from the UK to China. China exports; it doesn’t import,” Dalgety noted.

Recalling his first shipment of corilla bush out of Guyana, Dalgety said, “The customs officers saw us with it and put us at the front of the line, while they gave everyone with their pineapples and exotic fruits a hard time. I think they felt sorry for us.”

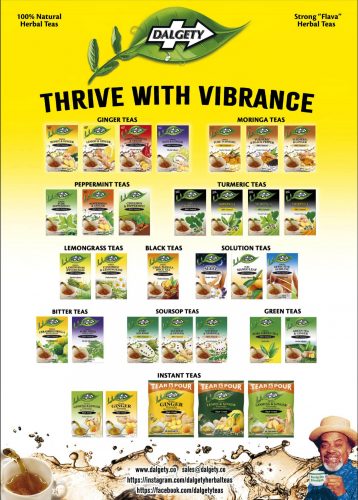

After corilla bush, Dalgety Teas developed other bitter teas, lemon grass, peppermint, ginger-based teas like honey and ginger, peppermint and ginger, lemon and ginger, moringa tea and turmeric tea.

“The South Koreans love the instant teas like instant ginger, ginseng and ginger for energy and lemon and ginger. We developed a granulated formula that could be brewed in three seconds as opposed to three minutes,” he boasted.

Today’s wellness teas for slimming and for sleep were developed based on requests, trends or listening to the market, Dalgety said.

“We don’t test our products for medicinal properties or shout about the health benefits. We test to ensure they are of the highest quality and standard, and to ensure their full potency. Most people who drink herbal teas know about their particular health benefits. The idea of drinking herbal teas is to build the immune system to prevent you from getting sick. Our objective is to turn herbal teas into a lifestyle,” he said.

Getting started

A chemical engineer by profession, Dalgety travels regularly between Guyana, the UK and West Africa. He is married, with five children born in the UK, and he and his wife run the business. His three younger children are in Guyana because he wants them to have some Guyanese education. “My Guyana education made me who I am. I want them to experience an environment that I grew up in, to understand their heritage, and not to get lost in the western world,” he said.

His aim was to live in Guyana. “When I started to build the business I ended up back in the UK. When I was heading back to Guyana, I started building markets in West Africa. England was my base until a few years ago; my wife said, ‘Let’s bring the kids back to Guyana now’. She returned and wherever the kids are, is the base. Twice a year I come to Guyana.”

Dalgety was born in England to Guyanese parents who were studying in London in the early 1960s. They sent him to Guyana when he was one year old. He attended Watooka Day Primary and Queen’s College. After writing the General Certificate of Education Advanced Levels examinations, he worked for a year at the Government Analyst Department before moving to study chemical engineering at London South Bank University in England. After university, he spent a year as a trainee plant manager with a cornmeal processing company.

“I was trying to relocate to Guyana, looking for an opportunity to make money. I was broke. I had a mortgage in London. Most people start a business because they have some money in the bank and they’re looking to multiply that money. In my case I started because I was broke,” he said.

Though his passion was in manufacturing systems, Dalgety never imagined himself manufacturing tea. When his parents sent him to Guyana, he lived with an aunt who was diagnosed with diabetes when she was 35 years old. She used corilla bush tea to control it throughout her life. She lived to 84.

“When I started making the corilla bush tea bags, I sent them to her. To see someone who has used the product to control diabetes for over 40 years is a testimony that the product works. When she was using corilla bush tea, I never thought I was going to get involved in that for a career,” he said.

In his teens, Dalgety suffered from pimples on his face. His cousins in the USA sent him creams and lotions that were not effective. Then his aunt told him to drink corilla bush, he said, “It was bitter. It may be the worst tasting tea but it may be the best one for you. When I started drinking it, my face started healing and that was the end of my pimples.”

One day in 1993 in London he met a Guyanese Chinese grocer who asked him if he could get him any amount of corilla bush, also known as cerasee in Jamaica or bitter melon plant. He thought it was an unusual request.

“I took a leap of faith. I had £1,000 pounds in my credit card, available. I jumped on the next flight to Guyana, went to Nismes, West Bank Demerara where my grandparents grew up and collected about 1,000 pounds of corilla bush. At our North Ruimveldt home I cut them up into 16,000 one-ounce packets, shipped them to London, sold each for 50 pence and earned about £8,000.”

He then decided to see what was going on in the market. So on another day in Brixton, London, a shopkeeper laughed at Dalgety for trying to sell corilla bush tea. “He asked me, ‘Where is the tea bag?’ We made a joke about it but that sat in my head.”

Dalgety did some research and found that most of the herbal teas were all nicely packaged but they were not 100 percent natural. “I decided to introduce to the UK and European markets 100 per cent strong-flavoured teas synonymous with the Caribbean. My first factory was set up in 1995.”

Dalgety then spent much time building the Dalgety Teas brand in cosmopolitan areas of London, Manchester and Bristol with highly-populated ethnic markets of migrants from the Caribbean, Africa and Asia. “You won’t see our product in Scotland or in the deepest part of Yorkshire. I looked at the section of the market I could penetrate without much costs. Corilla bush is not a product that every European knows about. Most Caribbean, African or Asian people know about it by some other name.”

For Dalgety, one of the natural routes to expand globally was to follow the consumer base, such as Nigeria and Ghana in West Africa, that he sold to. “We had traders from Nigeria and Ghana, with combined populations of over 285 million, buying our products so we thought it would be the natural thing to move there. We looked at other markets in South Africa and the countries in East Africa. The way I built the business in the UK was different to how I built it in West Africa. Once I was on the ground, I engaged the villages.”

Dalgety Teas also had a South Korea customer who took back a suitcase of teas to his family and friends when he travelled. He eventually became a distributor in South Korea and Japan.

Sourcing, CSR

In the early days, Dalgety Teas sourced most of the corilla bush, lemongrass, moringa and soursop from Guyana. Because of the quality and quantity required, Guyana alone could not meet the demands, so Dalgety Teas bought from Caribbean countries, West Africa, Asia and secondary importers in Europe.

“In Guyana, we couldn’t find a farmer with 100 acres of lemon grass or corilla bush. We found about 100 farmers with one acre or a patch of land where they grew lemon grass. We’ve worked with hundreds of farmers over the years to reach our requirements. We’re doing that now in underprivileged communities in West Africa. What we were/are doing is also corporate social responsibility (CSR) though we did not know that at the time. Working with underprivileged communities, we realised we weren’t just working for ourselves and our family but we are working for a lot of extended families. It could be minus degrees in Europe. We have to sell that tea because people are depending on us,” he said.

Dalgety Teas has a buying hub at La Bonne Intention, East Coast Demerara with two core employees whose main duty is to outsource materials to London. For the first 15 years, the company focused primarily on buying from local suppliers. They now have over 100 local suppliers. The company also obtains materials from a few villages in Ghana and India where they have over 300 suppliers.

Dalgety Teas are sold in most of the major supermarkets in Guyana after he was advised by a US importer of the product to make Guyanese aware of what Guyana offers internationally and because Guyanese in the US told him they have shipped the teas in their barrels to Guyana.

Dalgety Teas production facility is in London. However, they outsource some of their production to other companies because of the global expansion.

Challenges

“One of the first challenges I faced when I tried moving the corilla tea from packets to tea bags was getting the

quantity of corilla bush needed. I had gotten the first 1,000 pounds myself. I asked the guys in Guyana to get me another 2,000 or 3,000 pounds. I sent the money. They were just waiting to hear that my request was a mistake. When I told them to ship because I had the preliminary orders for the tea bag version, they only had 100 pounds. That was a setback,” he noted.

Other challenges included obtaining good quality tea bag machinery. “At the minimum it would cost about £20,000, excluding chopping and blending machines. It is an intricate technology to invest in until you do it right. I got out of that constraint by just selling packets of tea.”

Recalling the first time he went to a bank manager in London, he said, the manager could not believe that a Black man from a country like Guyana was trying to sell tea to English people, the tea connoisseurs of the world. “He asked me, ‘Are you sure about this young man? We sell you tea, you don’t sell us tea.’”

Dalgety then met a Black bank manager who grew up in the Caribbean. “He laughed at me saying, ‘You’re trying to sell the English bush tea. It isn’t going to happen here son.’ He didn’t understand the herbal tea concept, that when bush tea gets to England it becomes herbal tea, a premium product in Europe and more expensive than coffee or regular tea.”

During the credit crunch in 2009, with prices going up and unemployment rampant, Dalgety decided to set up a tea bag factory in Jamaica to cut production costs.

“I took advantage of the Jamaican government’s investment programme, got duty-free concessions, shipped machinery, vehicle and other things to Jamaica. I employed the first ten Jamaicans who arrived at the door. They damaged the machinery and they sent poor quality tea bags to the UK. I ended up with two factories, the one that was supposed to lower the cost of manufacturing and the one with the higher cost of manufacturing in London. The London factory had to do over those manufactured in Jamaica. Instead of lowering my manufacturing costs, I ended up increasing my manufacturing costs which almost collapsed the whole business. I closed the factory in Jamaica.”

On his return to London from Jamaica, he took part in a one-week course on how to employ people at the University of Greenwich where he met his operations manager, an Eastern European national. Together they worked on acquiring ISO 9000 certification. “We turned the business around and doubled the turnover in 24 months by employing the right people and putting the right procedures in place.”

In Ghana, he said, “We started off well. Initially, I did most things myself with the assistance of a business associate. Then I brought in consultants for things I didn’t understand. I then put someone in Ghana from England to run the business. He basically ran it to the ground. I got rid of him and that was how I ended up being in Ghana to reassess the situation and take the bull by the horn.”

On the positive side, when he arrived in Ghana, he related the story of the 1763 Berbice Slave Rebellion led by Cuffy to his business associate, who was of the Ashanti people. “The Ashantis said his real name was Kofi but we in Guyana called him Cuffy because we spell it how we pronounce it. I was invited to the Ashanti king’s birthday because of my narration, so I took the opportunity to present the palace of the Ashanti king with Dalgety Teas.”