The sources on which Clive McWatt relied for this account are located in the British Guiana files in the National Archives, Kew, London.

By Clive Wayne McWatt

‘Art? My Eye! – Mammoth clunk of sculpture for P.O. – Mr & Mrs Georgetown pass verdict’ This headline appeared in the Guiana Chronicle of July 4. 1950.

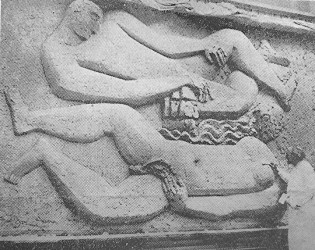

It was engendered by an article published in the London Evening Standard of June 23, 1950 and set off a public furore in Guyana. It told of a full-scale clay model of a high relief sculpture destined for the General Post Office in British Guiana being exhibited at Frank Dobson’s studio at the Royal College of Art in South Kensington, London. A preceding article in the Manchester Guardian on July 12, 1950 was accompanied by a photograph of Frank Dobson working on his full-scale clay model of the sculpture. The British press was full of admiration for Dobson’s designs: The London Times of July 24, 1950 referred to the sculpture as a “remarkable bas-relief.” These positive reactions were in stark contrast to the reactions of the vox populi of Georgetown who would come to detest this addition to their new GPO building.

Rebuilding from the ashes

The Georgetown fire of February 15, 1945 had devastated some of the prime commercial and public buildings in the city centre, including the original General Post Office building. The now familiar Georgetown city centre buildings – the Guyana Museum, Guyana Stores and the GPO building, were all modern constructions dating from the 1950s regeneration scheme after the fire.

Reinforced concrete and hollow clay blocks were the new building materials used as a replacement for the traditional wood structures that perished in the conflagration. Not only were these new buildings better designed to withstand fire damage, but the architects also embraced the new architectural design ideas that had been developing in Europe in the 1930s by the Bauhaus, Le Corbusier and the Modern Movement. The architects designed the new Georgetown buildings along horizontal lines with flat roofs and low towers as exemplified by the Sandbach Parker building, Booker’s Universal Stores (Guyana Stores) and the GPO building. The addition of squat towers designed for these new buildings were reminiscent of the old towers of the RA&CS building on Water Street and the General Post Office tower which had dominated the Georgetown skyline before the 1945 fire.

Architectural sculpture

The embellishment of important buildings with sculpture has been a tradition of every civilization with any pretension to culture since the dawn of history. In commissioning the British sculptor Frank Dobson to design a large decoration in high relief for the exterior of the new GPO in Georgetown, the architects W H Watkins, Gray & Partners were following a design tradition which went back to the Parthenon. They determined that sculpture was absolutely necessary for an important building like a General Post Office.

Frank Dobson (1886-1963), was regarded by many in Europe as the finest sculptor of his age; his contemporaries included Jacob Epstein and Henry Moore. After World War II he built up a reputation as a fine artist in spite of sustaining a fractured left arm in 1933 which severely restricted his ability to carve. He was Professor of Sculpture at the Royal College of Art from 1946 to 1953 and was elected to the Royal Academy of Art in 1953.

Dobson’s commissioned sculpture relief for the new GPO building measured 6m x 3m. The clay model was to be cast in cement and crushed granite and the end product was to be shipped from London to Georgetown in sections for re-assembly on the face of the tower of the new Post Office building. The design depicted a recumbent male and a female nude figure with the suggestion that they are floating in water; thus the main kinetic rhythms in the modelling were meant to suggest a movement of circulation, appropriate for the transactions of the Post Office.

Public outrage

The public furore in Guyana, which was sparked by the publication in the London press of the photographs of the sculptured relief and which was still at the clay model stage, rumbled on for several months in the local Georgetown press and the general public freely voiced their indignation over the proposed sculpture.

The strength of these feelings was demonstrated in the editorial which appeared in the Daily Argosy of June 30, together with a photograph of Dobson’s creation, with the headline ‘Wrong Thing, Wrong Place.’ The leader concluded:

“We do not know what proportion of the million dollars our new General Post Office is to cost has been allocated to this fifteen-ton monument, but frankly we cannot regard it, whatever it is, as money well spent.”

In a letter to the Chronicle headed ‘If this is art!’ the writer expressed his invective in verse:

I scorn this Art

And would have none

Of such, it chills the bone,

Shame! That our town

Be scarred with

Frankenstein and

headless crone!

In a letter to the Daily Argosy of July 5, 1950, headed ‘That sculpture,’ R G Sharples, then President of the Guianese Art Group, wrote, “… people will regard it if placed on the façade of the Post Office as being indecent, even obscene.”

Yet Sharples deemed the sculpture quite acceptable as a design to be exhibited in an art gallery. As a fellow artist himself, Sharples was careful not to deride the work of Frank Dobson and acknowledged the sculptor’s technical design skill. He raised instead the issue of Caribbean artists who were equally creative with the ability, technical attainment and skill to be able to execute a decorative design for the new Post Office. To this effect, Sharples suggested to the government that West Indian artistic talent be enlisted in the search for a suitable design to replace the one which the Guianese public had rejected, and a proposal was made that the Guianese Art Group undertake to set up a competition.

‘Perhaps some less advanced sculptor…’

The artistic controversy that had been stirred up in the Guyana press and voiced by the Georgetown populus made its impact on the government of the day. Behind the scenes in official circles much correspondence was shuffled between Governor Sir Charles Woolly in Georgetown and the Colonial Office in London, involving the officials in Whitehall and the architects. Woolly included a copy of the Argosy editorial in his despatch to the Colonial Office stating that “the design is utterly unsuitable and further work should be stopped on it at once.”

He asked that the Colonial Office contact the architects, Watkins and Partners and arrange for all work on the project to be suspended. He accepted that “Dobson will have to be paid for what has been done” and went on, “perhaps some less advanced sculptor can produce a suitably elaborate edition of the Colony’s Arms or something of that nature instead.”

The architects wrote to the Colonial Office agreeing that further work on the sculpture would be suspended but not before they drafted a strong defence for their choice to have the piece of sculpture on their building, stressing its importance as a work of great international repute from an artist like Dobson. They considered the work a masterpiece and set out to persuade the Guyana public, hoping at this stage that the finishing touches still to be made to the clay model would dispel some of the criticisms being made.

The architects had an ally in Mr Castello, the Planning Officer of Georgetown, who made an impassioned plea to the Colonial Secretary to get Dobson’s work to be accepted. Castello accused the Daily Argosy of being “prepared to have this Colony preserved as a backwater in matters pertaining to art.”

In the end the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London and the Governor capitulated to the views of the Georgetown inhabitants where the use of Professor Dobson’s sculpture was concerned. In a letter which ended: “In the circumstances, we should be glad if an alternative design could now be prepared and submitted to this Government for its prior approval.”

Dobson’s sculptured relief which was commissioned for British Guiana in 1948 was never to adorn the Georgetown Post Office building. Nothing further was heard of the sculpture; it is likely that the clay model was allowed to disintegrate after work on it was abandoned by the sculptor. Frank Dobson, however, remains an important British artist. Many examples of his work can be seen at the Tate Britain Gallery in London and Dobson’s ‘London Pride’, a bronze sculpture, was a major feature at the Festival of Britain in 1951, and was seen as a fine example of a work by a British artist. The bronze figures now sit in repose outside the National Theatre on the South Bank of the Thames in London. This and other works of art are testaments to Dobson’s status as a great artist of figurative monumental design.

Today Georgetown would have possessed a piece of sculptured art worthy of international repute. But this was not to be; the work of art destined for the GPO building was vehemently rejected by the people of Guyana.