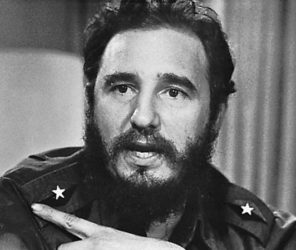

Thousands of eager Guyanese turned out to greet Cuban president, Fidel Castro on his whirlwind trip to Guyana in September 1973, while Prime Minister Forbes Burnham mused that the United States could get rid of three troublesome Caribbean leaders in a master stroke by sabotaging the Soviet-made airliner carrying them to a Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) meeting.

The cosy leftist trio of Castro, Burnham and Jamaica’s Prime Minister Michael Manley symbolically departed Trinidad for the Fourth Summit of NAM leaders, in Algiers, Algeria from 5 – 9 September 1973, on a giant Ilyushin 18 turboprop jet organised by the Cubans. One of the best known planes manufactured in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), it was far too big to land at Guyana’s Timehri airport so the communist leader and his delegation travelled between Port of Spain (POS) and Georgetown on a smaller aircraft for the official visit.

Barbados Prime Min-ister Errol Barrow’s “initial enthusiasm waned” and Trinidad and Tobago’s (TT) irascible Eric Williams decided too, to decline Castro’s free transport invitation, stay home and send representatives to the NAM conference who travelled independently. But the “Big Four” bosses all met with the Cuban President in the twin-island capital.

Summoned to a sudden Saturday session at Burnham’s Belfield rural residence on the eve of Castro’s touchdown, US Ambassador to Guyana, Spencer Matthews King reported that the Guyanese chief seemed “unusually subdued and tentative” yet “determined and intransigent.” He persisted with the erroneous conviction held for “some time” that the United States (US) would change its policy towards Cuba before long and seek “an accommodation with Castro” or rappro-chement, the representative complained.

“I assured him I had seen ‘no cracks in the wall’ and we then argued about Cuba for a time as we have done interminably in the past,” King confessed. “I (again) challenged his assumptions but without noticeable effect other than a concession that he really did not trust Cubans completely, but the world is changing, Guyana must trade where it can, everyone has to take some risks etc.”

“I found Burnham somewhat ill at ease, perhaps defensive. As our conversation opened with talk of Fidel Castro’s imminent arrival and Burnham’s plans to fly to Algiers with him. Burnham said this served Castro’s purposes as well as his own. Castro would gain respectability and he would put another nail in (Opposition Leader) Cheddi Jagan’s coffin. I commented that this was exactly what disturbed ‘Washington’— that Castro would gain respectability and acceptability and wondered whether it was wise from Burnham’s own point of view to identify himself so closely with the Cuban leader.”

King posted: “I joshed him and expressed the belief that the Soviets would be here sooner or later. He retorted ‘I would expect it to be later rather than sooner.’ I said perhaps they would look to the North Koreans, the East Germans and/or the Cubans to do their work for them. Did he expect any of these to have a presence here? He replied in the negative and went on off on a time-consuming and probably deliberately evasive discussion of the roles of Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Poland as Soviet tools.”

“As we parted Burnham said maybe the Ilyushin would not make it to Algiers. In which case the US would be rid of its three most vexatious problems in the Caribbean. I said this was not how we would hope to solve our problems and wished him a safe journey,” he recalled.

The charismatic Castro spent 26 packed hours visiting Georgetown and Linden, “with large and enthusiastic popular turnout,” the Ambassador said in a State Department brief, but he made no speeches and his busy schedule allowed only quick talks with Guyanese officials.

Castro swept in on the afternoon of September 2 to a warm welcome and “curiosity and enthusiasm” from the Guyanese with “reportedly” 3,000 persons crowded at the airport and many others lining the route into Georgetown. Embassy officers estimated “another 1,000 to 1,500” people outside the Main Street residence of State President Arthur Chung.

“After dining with Deputy Prime Minister (DPM) and Minister of National Development Dr Ptolemy Reid, Castro attended a large reception held in his honour at the residence of the Prime Minister, which turned into virtual mob scene as some 6,000 attendees broke through police lines and barriers in total breakdown of discipline in frenzy to see and touch the ‘revolutionary hero’ as one paper described him. Among the Diplomatic community, the Americans and Brazilians did not attend, but all others did, most notably Colombian and Venezuelan Charge’s (d’affaires),” King relayed.

Castro planted a palm tree near the Company Path Garden monument to NAM founders Yugoslavia’s Josef Tito, India’s Jawarhalal Nehru, Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt and Kwame Nkrumah from Ghana. In his declassified dispatch, King described the heavy turnout for the Castro motorcade on its way to Linden on September 3.

Driven to the mining town accompanied by Minister Desmond Hoyte, the Cuban President spoke fleetingly to bauxite workers, “his only public comments of entire visit. Castro said Guyanese were running bauxite operations better than the Canadians who owned them prior to nationalization in 1971.” He added “people kept in poverty and backwardness by imperialism need to recover own re-sources,” King accounted.

Castro and Burnham left together for the POS caucus to join host PM Williams, Manley and Barrow to discuss issues ranging from independence for Puerto Rico to Guantanamo’s return to Cuba.

In his missive titled “Fidel and Forbes and Eric and Norman” the US Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM) in Trinidad, Jay P. Moffat recounted “a frenetic day of Caribbean summitry” and full bilateral and collective consultations on September 4 when “Castro arrived from Guyana with Burnham in tow for dinner with Williams, Barrow, and Manley (who had presumably talked themselves out at lunch) before bearing Manley and Burnham off in the early hours of this morning for Algiers.”

Pointing out the Embassy hoped “to glean some of what went on from the still rather dazed participants or observers remaining here,” Moffat felt that the fact of the meeting outweighed the content for the TT Government.

“The get-together represented a visible step toward the Caribbean cooperation sought by Williams, dramatized TT’s ‘independence’ from the U.S, and undercut domestic opposition and lent some zip to an unpopular GOTT lately beset by internal problems.”

He remarked on the absence of negative feedback and public interests in US views on Cuba, pointing out “the new Brazilian Ambassador got nowhere on the subject of Castro’s visit with Williams.”

Guyana’s Dr Jagan boycotted Burnham’s reception for Castro under the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) policy of non-cooperation with the Government, because he was upset over the notorious July 16 1973 national elections which even the US privately ruled as “blatantly fraudulent” resulting in the main party boycotting Parliament. Jagan’s wife Janet had pleaded in vain with the preparatory Cuban team to dissuade Castro from coming, terming it a betrayal.

“However at least publicly, Jagan welcomed Castro. Placards on PPP headquarters read: ‘PPP welcomes Fidel, down with Guyana’s Batista regime’ ” King observed

While perturbed by the results, the US ignored the ongoing poll irregularities and steadfastly refused to openly condemn the vote rigging given that their only other option was the hardline Communist PPP, with one diplomatic message cynically noting it is “worth remembering that we would not have welcomed contrary outcome of election – that is Jagan’s accession to power. We can and must deal with Burnham government ‘as it is.’ ”

Following the undemocratic polls, King wryly accepted that with the more than two-thirds majority “Burnham has retained power” and “he will be able to amend the (Guyana) constitution as he sees fit. As the US had in past devoted much time, effort and treasure (sic) to keeping Jagan out, we should perhaps not be too disturbed at the results of this election – Jagan is still out, and Burnham is still in.”

In a damning bulletin, the Ambassador admitted that “in attempting its forecast of this election the Embassy had not really expected (Burnham’s People’s National Congress) PNC to abandon all pretense of honest elections.”

But “whether out of fear, confusion, inefficiency, exuberance or sheer lack of coordination, rigging does seem to have gotten out of hand. From all reports, ballot boxes were delivered by a variety of means Monday night (July 16) to Guyana Defense Force (GDF) headquarters in Georgetown where they remained under armed guard for upwards of 10 hours before vote counting began” with much “stuffing and switching.”

Brazen Burnham bluntly “ridiculed” PPP’s rejection of the results. “He said the PPP has neither power nor capacity to do anything about it,” King informed his superiors.

In the weeks before, American diplomats toiled behind the scenes unsuccessfully, to convince fellow firebrands Manley and Burnham not to travel with Castro, with King seeking the assistance of “moderate” Foreign Affairs Minister Shridath Ramphal.

Ramphal argued that even as “risks certainly existed,” pulling out would be “very difficult” causing Burnham to antagonise Castro with serious local and foreign implications. “To decide now not to accompany Castro would expose Burnham to charges by Jagan of succumbing to US pressure and reduce his non-aligned credibility at Algiers,” he posited.

Cuba’s United Nations Permanent Representative stopped in to solicit support for the island’s view that although the world had two super-powers and NAM, only one, the US was “imperialist.” Ramphal affirmed to King, Guyana reiterated “that non-alignment meant preservation of independence of action of all developing countries.”

Eventually the US State Department gave up and ruefully acknowledged that while there may have been a slim chance to dissuade Burnham from accompanying Castro to Algiers” it concluded “any attempt on our part to convince (him) to cancel Castro’s visit would probably be unsuccessful.”

On August 13, Burnham quietly informed King of Castro’s upcoming stay but divulged nothing about his intentions to voyage with Castro, following the return from Cuba of Dr Reid, where the DPM had attended the 20th anniversary celebrations of Castro’s aborted July 26 attack on the Moncada Barracks, in Santiago. Dictator Fulgencio Batista granted the survivors a fateful amnesty and released them from prison in 1955. They fled with Castro to Mexico and formed a guerrilla force returning to Cuba and launching the Revolution that toppled Batista in 1959.

Months earlier, King rushed to Burnham, concerned about Barbadian press statements that Cuba would soon establish resident missions in the four major capitals of the English-speaking Caribbean. Burnham replied there would be no such Georgetown Cuban Embassy until Guyana established one in Havana and his Government could not afford it in 1973.

“Havana has a relatively low priority, the Prime Minister went on… Someday, he concluded, Cubans will be here, but not right away.”

That tumultuous year Cuba and Guyana agreed to historic trade deals and air service between the two and “points beyond.” The growing close relationship eventually led to the Cubana 455 flight twin terrorist bombing on October 6 three years later and the deaths of 73 including 11 Guyanese.

ID as a young gradeschooler cheered Castro’s entourage, but as he makes his final Cuba crossing, she tries not to dwell on the 1973 Guyana dollar value of $2 to US$1 or the consequences of Burnham living to 90 and Hoyte not yanking the country back from the abyss in 1985.