PORT-AU-PRINCE, (Reuters) – A month before Haiti’s decisive presidential election run-off, the political figure getting all the attention is not a candidate, and he is not even in the country.

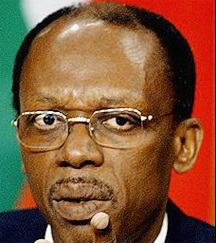

Exiled former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide’s plan to return home is making waves in his volatile, earthquake-ravaged country as it heads for a March 20 run-off vote after weeks of political turbulence and uncertainty.

A firebrand left-wing populist, Aristide is loved by many of Haiti’s poor but loathed by business leaders and the wealthy, and his announcement that he intends to return has triggered alarm bells in Washington and elsewhere.

He became Haiti’s first freely elected president in 1991 but spent much of his first five-year term in exile after a military coup.

Elected again in 2000, his second term was soured by economic instability and gang and drug-trafficking violence. He was finally ousted in a 2004 rebellion which included former soldiers. Aristide claimed it was orchestrated by Washington.

He insists he will now go back to Haiti, although he has kept everyone guessing about the timing.

Haiti’s government, under intense international pressure to keep shaky U.N.-backed elections on track, has said it cannot keep a citizen from returning and has issued a diplomatic passport for Aristide.

But the possibility that this could happen before the March run-off has led the United States, the United Nations and other major western donors to signal they would view such a move as, at best, unhelpful, and at worst, potentially dangerous.

“Knowing this, it would seem that if he truly wanted to help Haiti, he would remain away at least until after a new government is sworn into office,” said Mark Schneider, senior vice president of the International Crisis Group think tank.

Aristide’s supporters denounce what they call a campaign of political demonization against him. They say the United States and other Western powers want to tightly control Haiti’s reconstruction after the devastating 2010 earthquake and also the billions of dollars of foreign aid needed to pay for it.

Few doubt that the charismatic former Roman Catholic priest still commands a passionate following in Haiti and is potentially far more influential than the two contenders vying for the presidency — former first lady Mirlande Manigat and singer Michel “Sweet Mickey” Martelly.

Aristide’s aides insist he simply wants to participate as a private citizen in Haiti’s post-quake recovery. He has said he will involve himself in education, not politics.

“I will return to Haiti to the field I know best and love: education,” he wrote in a recently published statement.

Reports of his imminent return have generated a thrill of anticipation in the capital Port-au-Prince: slogans like “Long Live the return of Titide (Aristide)“ have appeared daubed on walls that still bear the scars of last year’s earthquake.

A recent rumor that he was about to arrive sent hundreds rushing to the airport.

“We want to know when Aristide comes so we can gather a crowd to welcome him at the airport … the country is gripped by poverty and unemployment. It is Aristide that can save it,” said Belizair Dorwing, 39, an unemployed Aristide supporter.

“We believe it’s … a good thing for the health of the democracy of the country … for him to return,” said Ansyto Felix, an organizer of Aristide’s Fanmi Lavalas party, Haiti’s biggest political party.

Fanmi Lavalas was excluded from the first round of the chaotic elections in November because of previous registration problems, and some say this further mars the election process, which has already been plagued by fraud allegations.

But there are doubts whether Aristide will really stay out of politics, and critics see him as a polarizing figure.

“His return will cause tensions, he is not someone who will be able to speak a language to appease passions. He will do just the contrary,” said Rosny Desroches, head of Haiti’s Civil Society Initiative which supports the current elections.

Desroches, a former member of the so-called Group 184 front that backed Aristide’s forced departure in 2004, said there were fears his return could trigger a resurgence of the gang violence which U.N. peacekeepers, deployed to Haiti that same year, confronted and largely brought under control.

Some suggest Aristide could also face lawsuits for alleged abuses and corruption committed during his rule, a fate faced by former dictator Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier who shocked Haiti by returning home from exile in France last month.

Aristide supporters and some analysts see blatant political motives behind the pressure against his return.

“The United States imposes its will, as the most powerful nation on Earth, to keep in distant exile the deposed president of one of the weakest,” Aristide’s attorney Ira Kurzban wrote in an op-ed piece for the Miami Herald on Monday. He described both Manigat and Martelly as right wing-leaning candidates.

U.S. diplomatic cables revealed by WikiLeaks indicate that the United States and Brazil, a major troop contributor to the U.N. peacekeeping force in Haiti, are concerned about keeping the potentially disruptive Aristide out of Haiti’s politics.

One cable laid out a U.S. policy goal of making Haiti “a viable state that does not pose a threat to the region through domestic political turmoil or an exodus of illegal migrants”.

Even at the height of the political crisis in Egypt, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton felt Haiti was important enough to visit late last month to press U.S. support for revised elections results that put Martelly and Manigat in the run-off, excluding a government-backed candidate.