Cassava has long been an integral part of the staple diet in a number of Caribbean households; today, however, Caribbean Community (Caricom) countries are pressing this versatile root crop into service in pursuit of a critical contemporary mission. With the region’s food import bill now reportedly hovering somewhere in the region of US$3 billion annually, several territories are beginning to contemplate cassava in a more important role. Some territories, like Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados have gone much further.

While there is nothing either new or novel about the manufacture of cassava flour, rising international wheat prices continue to push the region’s agro-processing sector in the direction of producing more of the commodity in order to cut the importation of wheat and wheat flour mostly from North America. Last week, Barbados’ Minister of Health Dr David Estwick announced that plans are underway in that Caricom member state to increase the production of cassava as part of a project; the outcome of which is expected to be a reduction in wheat importation and consumption.

The project is being undertaken in consultation with bakers across the island and the Barbados Manufacturing Association (BMA) with a view to determining the best percentage of cassava flour that can be added to bread. Dr Estwick says that after such a determination is made the process of “working back” to determine what quantities would be needed “so that we can tell the farmers what acreage to plant.”

Barbados’ cassava flour plan includes the processing of cassava into noodles, vinegar and other products utilizing work done by the local Food Promotion Unit.

Help with the project will be forthcoming from Brazil and the minister says he expects local bread and biscuit manufacturers will move to acquire the necessary technology to manufacture the product.

Last year, Trinidad and Tobago disclosed that a project was underway there to produce, in the very near future, flour that contained thirty per cent cassava flour. The report indicated that farmers in Trinidad and Tobago had cultivated 300,000 pounds of cassava and that the authorities had already begun to discuss the wheaten flour import reduction level with bakeries and other suppliers.

The country’s Ministry of Food Production, Land and Marine Affairs in Port-of-Spain recently announced plans to produce a range of value-added cassava products for both domestic and export markets. Simultaneously, the Trinidad and Tobago Agri-business Association (TTABA) launched a contract production programme with farmers. Bakeries have also been offered grated cassava to be utilized in a range of other bakery products including pone, cakes, biscuits and buns.

The oil-rich twin-island republic appears to have slipped well ahead of the rest of the region in its attention to cassava as part of the country’s staple diet. Late last year the authorities announced that more than 1,000 of the country’s farmers are involved in cassava production and that it is seeking to create more than 4,000 jobs in the cassava industry, primarily in the agro-processing sector. This year the TTBA is to make available to cassava farmers mechanical planters and harvesters as the twin-island republic seeks to increase local carbohydrate consumption from cassava to ten per cent. Plans for cassava in Trinidad and Tobago also include the manufacture of extruded products like breakfast flakes and snacks from cassava while cassava waste will be used in the manufacture of animal feed.

Traditionally one of the region’s major producers of cassava Guyana produced approximately 21,000 tonnes of cassava in 2007. While Guyana is unlikely to be in a position to match Trinidad and Tobago’s investment in either the cultivation of cassava or in its attention to adding value to the commodity, the country’s food import bill, small in comparison to those of Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados has been attributable to its high consumption rate for locally-grown foods, including cassava. Late last year Agriculture Minister Robert Persaud announced that plans were afoot to produce fifteen new varieties of cassava in Guyana and that Guyana was working in collaboration with the Colombian-based Centre for Cassava Research (CLAYUCA) to expand local cassava cultivation.

Recent global reports on whole grain and high fibre foods ought to further sharpen the focus of Caricom countries on reducing wheat and flour imports. A January 2011 report from Global Industry Analysts Inc a California-based consulting network published a forecast which states that the global market for whole grain and high-fibre foods could reach over US$24 billion by 2015, on account of the growth of health and fitness consciousness among consumers in developed countries. “Hectic, unhealthy lifestyles and poor dietary habits have heightened concerns about imminence of obesity, cardiovascular and other diseases, leading to a massive shift away from harmful, processed foods. The growing popularity of healthier, natural and fat-free whole grain/high fibre foods and baked products will provide the required growth impetus in the medium-to-long term,” the report says.

The GIS report refers to the release of new dietary guidelines in the US drawing attention to the importance of whole grain and high fibre foods in response to “studies corroborating the harmful impact of diets involving high proportion of processed foods, consumers are awakening to the need for healthy food into their daily diet.” In effect the GIS report means that increased demand for wheat and wheat flour among the more affluent could render the commodity increasingly inaccessible to poor consumers in developing countries.

Caribbean countries seeking to pursue new cassava flour initiatives, will be spared the trouble of reinventing the wheel. Both the technology and the manufacturing methodology are widely available in South America and Asia. Thailand has become one of the leading producers of cassava, cultivating an estimated 17.7 million tonnes annually. Between 50% and 60% of this production serves as a raw material for cassava chips and pellets exported to Europe and elsewhere to be mixed into livestock feeds. Price instabilities associated with cassava products have pushed the country to add value to the cassava through diversified usage. The manufacture of cassava flour has been pursued as a solution. Additionally, cassava flour production has also helped reduce the country’s US$120 million annual wheat flour bill.

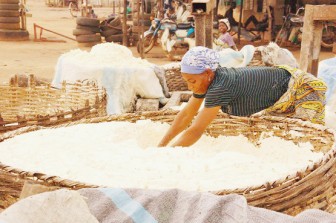

Cassava flour is also widely manufactured and consumed in South America including Brazil and Colombia where the culinary culture has fashioned a variety of cassava-based recipes. Companies in China regularly export 3 and 10-ton cassava flour machines to other parts of Asia, South America and Africa.

African countries too have a tradition of utilizing cassava flour. Small cassava flour mills can be found in some rural African communities in Rwanda and elsewhere. In Nigeria, a presidential initiative on cassava introduced eight years ago included a directive to bakers to include 10% cassava flour in the production of bread.

Since cassava flour does not contain gluten, it cannot be used as a 100% replacement for wheat flour with the same result. Suitable ratios for replacing wheat flour depend on the kinds of baked products being produced. Recipe guidelines suggest that cassava flour can replace 75% of wheat flour in sponge and chiffon cakes, 50% in butter cakes and cookies, 25% in doughnuts and spaghetti, and 20% in bread. Cassava flour can also be used to replace 25% – 50% of the rice starch in noodles, and will make the noodles softer and more elastic.

The successful introduction of cassava flour as part of the staple diet in the Caribbean will require that marketing methods address the issue of overcoming traditional tastes. Both Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago would appear to be aware of this. Both countries have said that the introduction of new cassava products, including flour, will be attended by public education programmes that will seek the acceptance of the product by local consumers. They will no doubt recall the experience of another Caricom member state, where restrictions on the importation of wheat flour and its substitution with rice-based flour, with little if any consultation with the populace gave rise to considerable resentment that is often recalled up to this day.