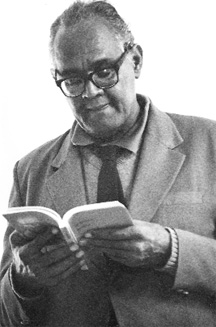

On the anniversary of Martin Carter’s death, and the 60th anniversary of the publication of To A Dead Slave and The Hill of Fire Glows Red, Gemma Robinson reminds us of the global reach of Carter’s work and its influence on writers and musicians.

In October of this year the University of the West Indies held its 30th annual West Indian Literature conference. This is an international meeting of scholars whose research focuses on the past and present of Caribbean writing, and its theme for 2011 was ‘I dream to change the world: literature and social transformation’. When I told Martin Carter’s eldest daughter and her visiting friend from schooldays the theme, they both looked at each other and said:

if you see me

looking at your hands

listening when you speak

marching in your ranks

you must know

I do not sleep to dream, but dream to change the world.

Martin Carter published those lines sixty years ago, in October 1951. The poem is “Looking at Your Hands” and it was first published in The Hill of Fire Glows Red. 1951 was a good year for Carter’s poetry. He had self-published his long poem, To A Dead Slave in May, and then in October he became the next poet in A J Seymour’s Miniature Poets Series.

What is not so well known is that this is a poem that right from its beginnings, travelled. By that I mean “Looking at Your Hands” has found a home in different places, at different times and with different readers. With this poem, as with so much of Carter’s other work, we can draw a map – we can create an atlas of the poem to tell us something about the pull and reach of Carter’s poetry then and now.

After the first modest print run of 100 copies of The Hill of Fire Glows Red had sold out, Janet Jagan organised a second to be sold at the PPP bookshop in Charlotte Street. Two hundred copies of this fiery pamphlet circulated around Georgetown and beyond, speaking of ‘Province of mud! province of flood!’, while imagining furiously for a future beyond colonialism and poverty. Here we find a revolutionary band of comrades pitched against its adversaries: the ‘mighty’ who constructed Guyana as ‘Plantation – feudal coast!’, the middle class woman who stares out from her window at the protesting poet, the ‘old higue’ who receives her folkloric comeuppance and the ‘idle men’ who waste their lives in the ‘bawdy house’. Joining the poet in the collection’s ‘furnace of life’ are Quamina (from the Demerara slave rebellion), the poet’s darling, revolutionaries in Vietnam, Malaysia and Kenya, the Enmore victims and survivors, the world of books, ‘the seller of sweets’, ‘the shoemaker’, ‘a black child in a kitchen’, an unknown ‘buried slave’, ‘the lame’ and ‘the mad’. All become part of Carter’s chorus, singing with him ‘the songs of life’ that might yet lead to that promised and promising ‘Tomorrow and the World’.

During the 1953 Emergency, “Looking at Your Hands” was republished and re-titled “I Will Not Still My Voice”. The change perhaps signalled a more pronounced challenge to the strange oppressions of the period, and the poem became part of the earliest versions of Poems of Resistance. In the new title, taken from the opening of the poem, we hear of the active power of the poet’s voice, rather than the contemplative statement of observation: different poems for different times and different places.

In this more insistently radical form the poem appeared in a range of publications that took Carter’s ‘dream to change the world’ out of Guyana to the United States and America’s radical presses, to the Colonial Office in Britain as seized literature, and to Trinidad as part of a West Indian protest against the Emergency. The poem along with five others was published in the left-wing US journal Masses and Mainstream, was confiscated from the Magnet Printery in Georgetown and sent for political scrutiny to London, and it was also recited and circulated in Port of Spain’s Woodford Square through a pamphlet produced by John La Rose for the West Indian Independence Party.

It is also worth remembering – and particularly during this 60th anniversary year of To a Dead Slave and The Hill of Fire Glows Red – that Carter’s work finds new homes all the time. Consider Guyana’s great scholar, Gordon Rohlehr, and his collection of essays, My Strangled City, which takes its title from ‘Not Hands Like Mine’. Or Grace Nichols’s novel Whole of a Morning Sky (a quotation from ‘Black Friday 1962’) and Stanley Greaves’s poetry collection The Poems Man – a nickname for Carter, and a role he wrote about but wore uncomfortably. Or Rupert Roopnaraine’s film, The Terror and the Time, that juxtaposed 1950s Guyana with the 1970s. Or the Jamaican British-based Linton Kwesi Johnson’s musical translations of ‘Poems of Shape and Motion’ on his album ‘More Time’, and most recently the Trinidadian rapso band, 3canal, who have returned to Carter as a voice to listen to in ‘the dark times’ (in the words of both Bertolt Brecht and Carter).

Carter’s voice sustained the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o, and when he published Decolonising the Mind in 1986 it was with Carter that he began and ended his study. He wrote: ‘The theme of this book is simple. It is taken from a poem by the Guyanese poet Martin Carter in which he sees ordinary men and women hungering and living in rooms without lights; all those men and women in South Africa, Namibia, Kenya, Zaire, Ivory Coast, El Salvador, Chile, Philippines, South Korea, Indonesia, Grenada, Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth, who have declared loud and clear that they do not sleep to dream, “but dream to change the world”’. Ngugi comes back to that reference in the final paragraph of the book: “Struggle. Struggle makes history. Struggle makes us. In struggle is our history, our language and our being. That struggle begins wherever we are; in whatever we do: then we become part of those millions whom Martin Carter once saw sleeping not to dream but dreaming to change the world”. Ngugi translates Carter’s words into a global challenge, and in his recent memoirs Ngugi extends this as the challenge “to have dreams even in a time of war”.

In Nigeria the poet, Odia Ofeiman, found Carter’s work and said: “Martin Carter’s prison experience talked of things Nigeria should be talking about. I had not read [Wole] Soyinka or [Christopher] Okigbo, but saw that poetry could do things”. It is not clear that Carter ever spoke as confidently as this about what poetry does, about what change in the world it might make. If poetry did things, for Carter it was in the realm of the performative moment, often in the register of a question, riddle or the conditional, in the mode of an attempt or a promise for the future. These are all important kinds of poetic action, and acts that complicated and complemented the other activities that he was engaged in throughout his life. Carter was always acutely aware of the other acts that might make up life, the demands and the duties that might compromise or provoke us into action.

That understanding of acting in the world became further charged when Wendell Manwarren from 3canal returned to Carter to consider the political state of contemporary Trinidad. In Thunder in January 1955 Carter wrote:

The year that lies before us will be a year of heart searchings, a year of doubt and perplexity, a year in which each one of us will question himself in secret, studying whether the path of life we now tread is the right one or whether a wrong one. In the midst of all the turmoil and confusion, there will be some whose convictions will crumble, some who will repudiate past activities, some who will say in an hour of fear that the road they have been walking is the wrong one because at the given moment all is dark and dreary and apparently hopeless.

In such times it becomes necessary for us to understand ourselves, the world we live in, the people we live among and the problems we must solve. At such times, ideas and emotion become inflammable. And it is at such times that our fundamental outlook on life, the means we employ of measuring and assessing events and occurrences, either assist us or betray us.

Words written during the suspension of the constitution and a state of emergency. At an event to celebrate Carter’s work in 2007 Wendell Manwarren read a 52-year-old statement and spoke of its resonance with Trinidad’s cultural and political crises. And he has been reading it again in 2011, in the light of Trinidad and Tobago’s controversial state of emergency which ended only last week.

Manwarren looked across period and place and found two states of emergency. He says ‘sometimes you have to take a little time to take a little pause, to learn from what others who’ve gone before this road have to say. So I am reading’. It is the same lesson that Carter learnt in 1951. In “Looking at Your Hands” that road of experience stretched behind him too: “I have learnt / from books dear friend / of men dreaming and living / and hungering in a room without a light / who could not die since death was far too poor / who did not sleep to dream, but dreamed to change the world”. 1951, 1955, 2007, 2011, all years of ‘heart searchings’ certainly, and times of ‘inflammable’ ideas and emotions, where contrasting colonial subterfuge and postcolonial politics seem united in their refusal to speak clearly about the fears and motives of those in power.

In 1990 in his unpublished notebooks Carter wrote: ‘Poetry: a way of surviving: If life is the question asking what is the way to die; poetry is the question asking what is the way to live”. Carter’s poetry exists in the spaces between living, dying, surviving and struggling, lamenting and celebrating these contradictions. From the poet who liked to sit on his porch in Georgetown as much as walk the city streets, we have a body of work that travels both near and far, from father to daughter, across the streets of Guyana and onto Woodford Square, to the British Colonial Office and the decolonising impulses of Ngugi and Ofeiman.

And in October 2011 Carter’s work travelled again, to a Port of Spain art gallery, Alice Yard, and was performed again in a state of emergency.

Fuelled by visual works by artists Marlon Griffth, James Cooper and Rodell Warner –work that the Trinidadian artist, Christopher Cozier, described as ‘a sequence in this ongoing process of transforming the value of our actions and the varied spaces in which we live and imagine’ – Carter’s ‘furnace of life’ expanded. The Jamaican-born science fiction writer, Nalo Hopkinson, read the haunting surrealist journey “University of Hunger” for her ‘Uncle Martin’, The Trinidadian writer, Barbara Jenkins, chose the revolutionary romance of “Shines the Beauty of my Darling”, and Trinidadian poet Vahni Capildeo’s rendering of “After One Year” was wrought through with contemporary damnation for the lost ways of politics.

Like Carter in times of crisis, Wendell Manwarren turned to the first lines of “Looking at Your Hands”: “No! / I will not still my voice / I have / too much to claim”. And more than this, 3canal’s set of songs (including rapso classics “Boom up History”, “Giants”, “Good Mornin’” and “Talk yuh Talk”) were introduced by and overlaid with Carter’s “This is the Dark Time my Love” and “Our Time”. The set was both incendiary and salutary: ‘You believe we in a State of Emergency right here right now?’ The packed crowd felt the elusive power of performance, and the pull of protest during times of political disappointment, confusion and curfew. But we also learnt something about the need to pause and to learn. In the words of 3canal and Manwarren – true readers of Carter – we are reminded that struggle must include the public will to challenge people and language (to ‘boom up history’ rather than swallow the talk of ‘yuh mocking pretender’) and that this is often borne out of a personal determination ‘to wrestle with a line on a page’.

Gemma Robinson is the editor of Martin Carter’s University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose (Bloodaxe). You can hear 3canal at http://www.3canal.com/.