Dear Editor,

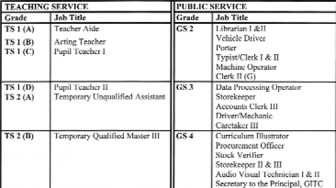

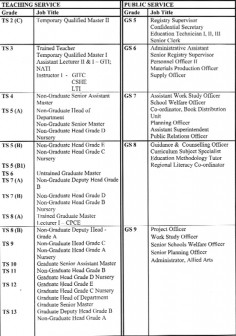

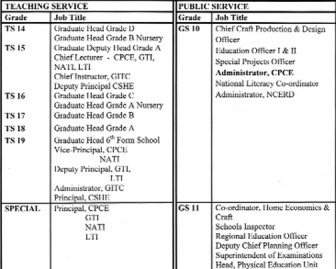

At the risk of straining the patience of readers on the issue of importation of Maths and Science teachers, the Table following provides an indicative sampling of public service (MoE) jobs vis-à-vis TSC jobs, in a manner that relates to the respective pay regimes shown in the Table in my earlier letter.

Comparative jobs structures based on broad salary relativities

Comparative jobs structures based on broad salary relativities (cont’d)

Comparative jobs structures based on broad salary relativities (cont’d)

It is arguable that the TSC structure places continual pressure on teachers to upgrade their formal qualifications in order to be eligible for promotion. Even so, their qualifications have to be supplemented by specified periods of relevant experience, all of which is subject to monitoring and evaluation.

With the possible exception of the performers in the health sector, there is hardly any group of public servants who are exposed to accountability, formal and informal, by employer and client students/parents, like those in the teaching profession. Whatever the assessed quality of performance, at least its patients survive what abortions may occur.

On the other hand, there is no explicit evidence that once in situ the incumbents of counterpart Public Service positions are under the kind of regime which insists on skills and/or education upgrading for promotion. Nor is there any consistent implementation of the performance evaluation system that subsists in theory in the Public Service. In fact the provision for accountability, overlooked over the last several years, has been replaced by the simple award of across-the-board increases.

Possibly more informed readers will identify other ludicrous (mis)comparabilities.

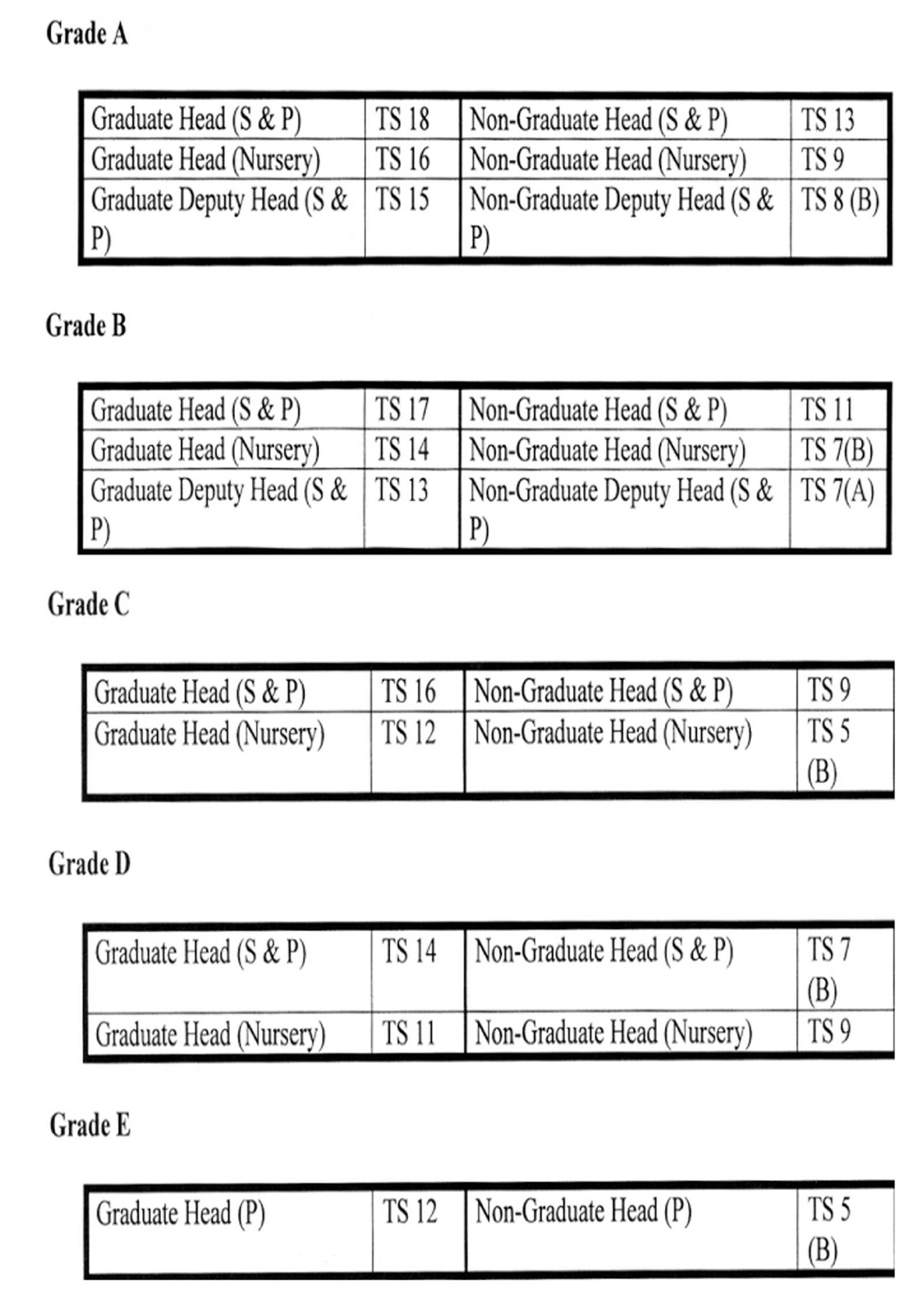

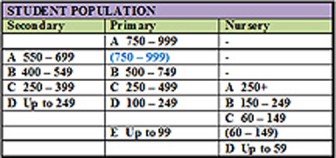

Grading of schools

The current system of grading schools must be regarded as a ‘condition’ which sorely needs to be addressed. This is done on the simple basis of student population – as reflected in the Table below:

School grading system

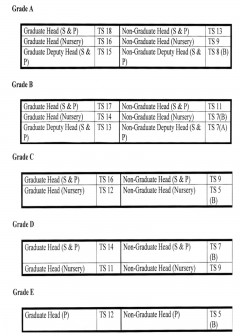

On the whole, the system of rating schools in the local education system, can at best be described as simplistic, suggesting, for example, that the nature of responsibility of a school head is generally measured by school population. This results in a major contradiction wherein occurs a substantive differential between basic remuneration paid to a ‘Graduate Head’ and that paid to a ‘Non-Graduate Head’ in relation to the same or similarly rated school. One is left to fathom the reasoning which determines a ‘Non-Graduate’ as capable of managing the same size school as a ‘Graduate,’ but at a level of payment as much as seven grades below that of the latter.

This convoluted system of rewarding teachers who at any level operate in a target-oriented environment, and are expected, both by their employers and client parents, to consistently achieve those targets (in the face of known constraints); as well as satisfy measurable performance criteria, yields (with minimal exception) an average annual salary increase of less than five per cent.

The disparities in pay, palpable as they are, can be interpreted from the grades shown in the following Table.

Comparative ranking of heads and deputy heads in same grades of schools

One would justifiably ask what all the above has to do with importation of teachers. The implications should not be too hard to discern, and include the following:

a) On the assumption that the ‘secondment’ of the requisite group of teachers can be effected, their assignment to the locations where the shortages in question are identified will presumably include the regions.

Predicting some reservations about regional postings, there is the option of increasing the ‘hardlying’ incentive; or of transferring local urban counterparts to make accommodation for the ‘guests,’ expected to be unfamiliar with our environmental constraints.

b) In any case the process of selection and recruitment agreed with the migrants’ employers will have to be consistent with the Rules of Caricom Single Market and Economy (CSME):

i) The remuneration packages to be constructed will vary in relation to the exchange rates operating in different Caricom territories.

ii) There must be provision for housing, possibly transportation, and financing of maintenance at the home base, eg medical and other miscellaneous expenses.

A budget will therefore have to be carefully worked out, that must in principle take into account the differentiation in pay related to the grading of the school to which appointed – an issue bound to be raised by the GTU.

iii) The authorities will furthermore have to satisfy the GTU about the apparent discrimination in remuneration which is bound to emerge from this exercise.

iv) The GTU, related training institutions and the Ministry of Education will, in the meantime, have to agree on a development plan to upgrade the number of qualified teachers to the declared ‘100%’, and to provide for the touted ‘excess’ to address the migration factor.

Indicators are therefore that the issue of increased remuneration for the local teaching profession should be treated as a priority on the Minister’s agenda. The ‘guest’ teachers could hardly be expected to stay for an indefinite period. Alas, this is just only a short-term project that would not resolve a fundamental human resources problem.

Yours faithfully,

E B John