GUATEMALA CITY, (Reuters) – The secrets from a vault of moldy documents long covered in bat and rat droppings could soon help to put former top Guatemalan officials behind bars, years after the country’s brutal civil war ended in 1996.

Clues found in the millions of police documents have lifted a lid on government repression during the 36-year war, and provided enough evidence to start sending cases to trial.

For the first time in Guatemala’s history, a former police chief now faces trial based on evidence collected from the national police archives, a labyrinth of dark rooms found by chance in 2005 when an explosion tore through a dilapidated building being used as a munitions dump.

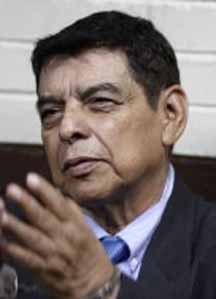

Hector Bol de la Cruz, former director of the national police, is charged in the case of Fernando Garcia, a 27-year old student activist who disappeared on Feb. 18, 1984 and was never seen again by his family.

The first hearing is on hold pending an appeal by a defense lawyer to remove one of the judges in the case.

Garcia’s relatives say the trial offers them the hope of finally finding out what happened to him.

“I think about how my dad would feel,” said Alejandra Garcia, Fernando’s daughter, who was a baby when her father disappeared. “He would be happy to finally see a little bit of justice in this country.”

The chaotic jumble of archive papers and handwritten log books are being dusted off, digitally scanned and backed up on secure servers outside the country by rights groups so that prosecutors can sift them to solve crimes from the civil war.

The process could take years, and the cumbersome work means that only three cases are now being processed using material from the archive, which houses 80 million pages of documents that stretch back to the 1800s and include portraits and profile information on suspected leftists, even down to their daily walking routes. Hundreds of other prosecutions could follow.

Families of roughly 45,000 missing leftists have contacted local rights groups to help them find information about their relatives in the archives. Prosecutors have projected images of the documents on courtroom walls to build their cases and win support from judges.

Guatemala made the documents accessible to the public in 2009, and some 12 million digitalized copies from the archives have been published online by the University of Texas at Austin.

Relatives of some of the civil war victims see the trials as ending decades of impunity for those who ordered the abduction, torture and murder of thousands of suspected leftists.

However, building strong cases is difficult and convictions of former security officials have been few and far between.

Human rights lawyers say success in the cases would bring Guatemala into the ranks of countries like Rwanda and Germany, which held former government officials and military officers responsible for atrocities.

A U.N.-backed “Truth Commission” set up under 1996 peace accords concluded that the military was responsible for more than 85 percent of human rights violations during the war, which claimed the lives of around 250,000 people.

But the army still has a powerful presence in Guatemala. Otto Perez, a retired general and former head of military intelligence, was elected president late last year and took office in January. Some fear he will be wary of letting war crime trials move forward, although he insists he won’t impede justice.

“The president cannot interfere with judicial proceedings,” Perez said. “We have no reason to remove those in the judicial branch who are doing their job well.”

During the conflict, police worked closely with the army to stamp out an armed guerrilla movement. The police archives could unearth evidence of those links, investigators say.