(MSN) – Cloud Atlas is the most sprawlingly ambitious ostensibly mainstream motion picture I’ve seen in years. The fact that it even exists is something worth celebrating. That doesn’t give the reader in search of practical knowledge much to go with, so let me get down to brass tacks.

You’re detecting a theme here, I bet. It is no accident, as Engels would say, that the impetus for the film version of “Cloud Atlas” should come from Lana and Andy Wachowski, who have made a career out of exploring the theme of human freedom via genre movies. Both their Matrix trilogy and V for Vendetta the movie they produced but did not direct, explicitly deal with the exploitation of the powerless by the powerful, how these relations come into being, and what is to be done about them. In Cloud Atlas collaborating with Run Lola Run and Perfume: The Story of a Murderer director Tom Tykwer (the Wachowskis and Tykwer directed three story lines each, respectively), they weld this theme to one of eternal return to create an umbrella narrative of eternal struggle.

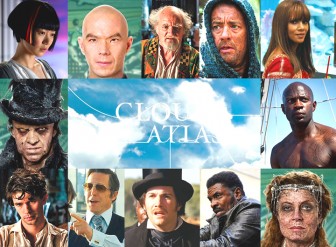

While Mitchell’s novel took the form of a nesting doll that is disassembled and then reassembled, going forward in time to the tribal episode and then going back, the movie version intercuts between all six stories throughout its nearly three-hour running time. The same core cast (Tom Hanks, Halle Berry, Hugh Grant, Susan Sarandon, Hugo Weaving, Jim Sturgess, Ben Whishaw, Jim Broadbent, James D’Arcy, Doona Bae, Vun Zhou, Keith David, and David Gyasi), sometimes in highly outlandish makeup, is used throughout. The overall effect is dizzying, and some might say hard to follow. But it’s pretty staggering how, with editor Alexander Berner, the filmmakers are able to pound through multiple climaxes of the different stories in a way that’s both coherent and sometimes anxiously suspense-laden. Forget the Oscar; Berner ought to get some kind of Nobel.

However, about that all-star cast mentioned above … All of them put in a good deal of work, but for some reason very little of it connects. Hanks and Berry in particular stick out like sore thumbs throughout, particularly in the tribal 2321 scenes. This may be the fault of the material. I haven’t read the entirety of Mitchell’s book, but the sub-Faulknerian man-child language of the sequence’s dialogue would seem to have originated there, and it doesn’t work, as in it strikes the viewer/listener as false, a self-conscious contrivance.

In other respects, the on-the-nose iterations of the themes of connection are pretty risible. “One can transcend any convention so long and one can conceive of doing so,” one character observes, but when another character wistfully confides, “My uncle was a scientist, but he believed that love was real,” one realizes that sentimentality was one convention that the filmmakers decided not to transcend. This wouldn’t be so bad had some of the dialogue shown actual wit, but no. Similarly, the filmmaking itself, while incredibly advanced on a technological level, is kind of mind-numbingly literal.

Part of the point of the book was a virtuosic display of different literary styles, and the potential for a varied buffet of filmmaking styles is there in the material. In not taking advantage of that, the filmmakers allow a certain monotony of amplification to set in, in spite of the varying settings and breathtaking special effects. It’s kind of astonishing that for all its ambition and accomplishment, and for the ostensibly subversive philosophy it pushes, Cloud Atlas ends up being just another platitudinous, overblown, pummel-you-into-submission movie-machine. It’s a blue pill pretending to be a red pill.