‘Governor Trinidad confidentially warns [me] concerning F.E. Hercules negro race agitator in transit Georgetown in New York steamer Maraval, expected to arrive December 25, He was not allowed to land Trinidad. I would recommend deportation.’

Baker (British official): Cable from Port of Spain, to Secretary of State, Washington, DC December 17, 1919

By Nigel Westmaas

In 2010 the announcement by the government of former Guyana President Bharrat Jagdeo that a central intelligence unit had been established in the compound of the Castellani House art gallery drew public consternation with the choice of location. It also unintentionally highlighted a subject seldom publicly articulated: the role of espionage in Guyana’s past and present.

In Guyana as elsewhere there is sometimes a blur between police intelligence for crime-fighting and the collection of illegal information on citizens, or spying, which is much more complicated than the caricature embodied in Ian Fleming’s 007: it encompasses military intelligence, the Special Branch from colonial to contemporary Guyana, embraces international dimensions including border security, and today, draws on the all-pervasive electronic surveillance. By its very nature, accounts of espionage are also unable to rely on traditional research sources like published documents and open testimony. Thus, in probing Guyana’s espionage history one confronts an understandable lack of detail, and bits and pieces from new research; interviews with officials; court revelations; whistleblowers; everyday rumour and gossip; and the few Guyanese books on the subject are all inevitable, if slim, sources.

The narrative of espionage in Guyana potentially ranges from the activity of rebel slave leader and national hero Cuffy in the 18th century to that of the nefarious drug dealer and electronic spymaster Roger Khan in the 21st.

Espionage in slavery

The historical record shows that the early Dutch colonists had established alliances with Amerindian tribes to counter attack from outside (among other things) and at a later stage, counter slave resistance from inside. It is also known that during the 1763 uprising, Cuffy employed spies and built his revolt on sound intelligence about the plantations. Slaves in active rebellion benefited from a built-in advantage as they lived on the plantation and knew almost every detail of the diurnal cycle of planters and colonists, their defences, weaknesses and strengths. But as historian Alvin Thompson notes, the intelligence corps of the whites also “included faithful Africans and Amerindians.”

Henry Bolingbroke’s Voyage to Demerary was fulsome in its praise for a slave who spied for the Europeans in Guiana in 1795 in their bloody track-down of freedom fighting Maroons. In 1814, Lt Governor Henry Bentinck reveals, sensing a slave rebellion, Berbice planters procured a few loyal slaves to “ingratiate themselves with some of the disaffected slaves…to induce a disclosure of their designs…” One of the rebels, called Jem of Plantation Merville, was convicted of “assuming the situation of a Governor among the slaves, and of convening, frequenting and assisting at nightly meetings for seditious purposes…”

Fast forward

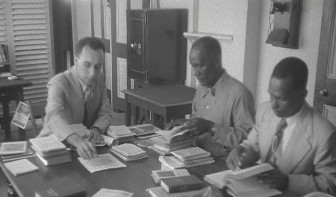

By the 1920s, Marcus Garvey and his ever-expanding Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) posed such a worldwide threat to the United States and the British colonial government that it prompted urgent telegrams (now declassified) by colonial officials, cautioning about UNIA’s activity in British Guiana and elsewhere. This was not unexpected. Garvey and his organization had became the subject of attention from then FBI director Edgar Hoover and the latter had managed to insert the first black agent in the FBI‘s history in the highest ranks of the UNIA. Across the Atlantic alarmist letters and telegrams between the local governor and Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, warned of Garvey’s impending 1921 visit to Guyana. (Garvey eventually visited Guyana in 1937.)

In both world wars, British Guiana was drawn into the realities of war including the danger of German espionage. In the Second World War German submarine threats and active British military intelligence outposts exemplified Britain’s wartime mode.

The external threat was not the only problem. Very quickly after the war the British panicked over embryonic organisations of local leftists and anti-colonial radicals in Guyana in the late 1940s and early 1950s. When the nascent radical movement won the first elections under universal adult suffrage in 1953, the removal of the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) by force was preceded by Winston Churchill’s “enthusiastic supporting preparations for British-American covert action.”

Sir David Rose, then police superintendent and chief security officer in the CID was actively involved in intelligence gathering and suppression of the activities of the early PPP. Rose was killed in 1969 in England when building scaffolding fell on him, and his record in the 1950s is largely unknown.

Declassified published information suggests MI6, Britain’s intelligence service dealing with foreign threats conducted espionage on leftists including Cheddi Jagan and his then colleague Forbes Burnham. At one point Jagan was actively under “discreet observation” and followed to and from his hotel in England.

The Cold War

In Guyana, the turbulence of the 1960s, with its ideological, political and ethnic divisions, manipulated by Western governments in the context of the global Cold War, held implications for local espionage. Western governments were active and Britain’s MI6 was said to have sought assistance in placing a Canadian as “special economic adviser” to Premier Cheddi Jagan.

In his book Justice the late Catholic priest Fr Andrew Morrison recounts attempts of the British spy agency MI6 to recruit him into espionage. In 1963 MI6 introduced Morrison to “the workings of the intelligence organisation” and a “cloak and dagger atmosphere prevailed…” Morrison was shown how to transmit secret messages and make “drops” but eventually told his MI6 handlers that as a religious person he could never be a secret agent. The CIA’s role with some Guyanese trade unions has been documented. The late Stabroek News publisher and editor-in-chief David de Caires likewise referenced an organization called SHOUP as a CIA front group whose primary task was to spy on leftists in Guyana.

Guyana’s frontiers

Venezuelan intelligence on Guyana was unquestionably active. One byproduct of the tension was the Beria spy plot of 1968. In a detailed press statement in November 1968 then Prime Minister Forbes Burnham unveiled detailed government surveillance of Pedro Beria, an alleged Venezuelan secret agent and member of the left wing Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR). Burnham explained that Beria “was under constant surveillance by Special Branch…” and that his “briefcase came into the possession of the police and with it a number of documents of the greatest importance to Guyana’s security…” While the press conference attempted to establish a link between the opposition PPP and Beria, it appears that with the later development of closer ties between the Burnham government and Cuba, the incident was allowed to evaporate from the historical narrative.

Public documentation is silent on whether Guyana possessed active intelligence machinery for neighbours with territorial ambitions such as Suri-name and Venezuela. For instance were there ever Guyanese “sleeper” agents among the thousands of its citizens in Venezuela and Suriname?

Espionage in

the 1970s

The 1970s saw a rise in international activity of the Burnham regime in assisting causes ranging from South Africa’s anti-apartheid struggle to providing logistical support for Cuban troops to land in Angola in support of the left-wing MPLA. The proliferation of embassies and missions associated with the Eastern bloc, Cuba, China and North Korea alongside traditional Western diplomatic representation placed Guyana directly within the geopolitical ramifications of the Cold War. In an allegedly “true life account” George-town Spies (1995), Dhanraj Bhagwandin, a former Guyana Chronicle and IPS journalist, described the activities of mainly Soviet and Cuban intelligence. He also maintains that British and American intelligence, with its longer if not entirely legitimate history in the country, was active. This account has all the verve of a classic espionage novel with spies gathering information on crucial segments of the economy and Guyanese personnel from all walks of life.

By the late 1970s the newly established Working People’s Alliance (WPA) became an active threat to the Burnham regime. The state’s response to the WPA and to Guyanese historian and revolutionary Walter Rodney in particular was frantic. Perhaps no individual in the anglophone Caribbean had received as much “intelligence interest” as Rodney. From Jamaica in the early 1960s all through his Tanzania and Guyana periods of residence he was a magnet for security interest because of his social and political activism. Accord-ing to Jamaican intelligence files, he first came to “security notice” in June 1961, when he and two other students accepted an invitation to attend a meeting of the International Union of Students in Moscow. For unknown reasons Rodney did not proceed to Europe but toured the Caribbean. The declassified material states that he “had a history of subversive action, agitation and organization of a Black Power movement, and the propagandization of Communism and violence in Jamaica almost since his arrival in January 1968.” When his regional and global activism eventually led him back home to oppose the People’s National Congress (PNC) regime led by Forbes Burnham, he was immediately placed under surveillance.

The panic of the late 1970s arose from the PNC’s perception that the WPA had penetrated the highest strata of the Guyanese military. Con-currently, the WPA was itself a target for espionage from the ruling party. Burnham, ever the sagacious deliberator, immediately reorganized the army and intelligence services. A consideration, in a diminutive society like Guyana, came from the logic that erstwhile school “friends” of these army personnel including Rupert Roopnaraine, Walter Rodney and others would have “befriended” and compromised the force. The late Police Commis-sioner Laurie Lewis was a prominent part of Burnham’s intelligence corps as was Godwin McPherson (deceased) for military intelligence. Columnist Frederick Kissoon previously mused over Lewis’s silence on security matters. Lewis, a former Chairman of the Joint Intelligence Services was cut from the cloth of an affable George Smiley spymaster character, and would have been an important source on Guyana’s intelligence past, especially as he connected the Burnham era with the second Jagan era.

The Roger

Khan era

The PPP government came to power in 1992. By 1997 the state apparatus still embraced a constitution that guaranteed enormous powers to the President and government. What Clive Thomas calls a “narco state” developed; corruption, the underground economy manifested in the drug trade and criminal enterprise assisted by electronic espionage capability were significant features of the new state. The spy equipment found in a truck at Good Hope belonging to jailed drug trafficker Roger Khan was a prime example of domestic espionage. Khan’s apparatus included sophisticated computer software that offered triangulation and other computer surveillance apparatus and methods capable of intercepting cellphone communication among other activities.

The Castellani House central intelligence unit officially becomes the eyes and ears of a party and government that holds a poor record of activity against crime and the drug trade in particular. When former President Jagdeo was confronted with criticism from the WPA about the new intelligence agency he blurted out: “We don’t need to spy on political opponents; if I want to find information I will just get somebody to go to the rumshop and they would give me all the information I need on political opponents…” While it is true that some secrets flow with alcohol it is also unfortunately true that state secrets are susceptible to the public drunkenness of a few members of officialdom.

Now the Guyana central intelligence unit is active what does the future hold? With the government’s capability to routinely break into e-mails, bug offices and engage in CCTV camera snooping, the concerns with spying, especially on activists in the political opposition, will only expand. The watchers will themselves have to be watched.