A country’s natural resources, such as oil, gas, metals and minerals, belong to its citizens. Extraction of these resources can lead to economic growth and social development. However, poor natural resource governance has often led to corruption and conflict. More openness and public scrutiny of how wealth from a country’s extractive sector is used and managed is necessary to ensure that natural resources benefit all.

EITI 2016 Progress Report

Last week’s article was devoted to a discussion of the issue of transparency in relation to the Georgetown Metered Parking project that has been suspended at the request of the Government amid pressure from key stakeholders. In passing, we had referred to calls from various quarters for the Government to release to the public the contract with ExxonMobil for the extraction of crude oil in Guyana’s waters. So far, the

Various figures have been provided as to the extent to which revenue will accrue to Guyana when production begins in 2020, the latest being US$380 million or G$78.47 billion annually. However, without the contract being made available, citizens have no way of knowing how this amount has been arrived at. What we do know so far is that: (a) a royalty of 2% on production has been agreed upon; (b) production will begin at a rate of 100,000 barrels per day; and (c) profits will be shared equally between ExxonMobil and Guyana after a deduction of 75% of the revenue to recover Exxon’s investment, estimated at US$5 billion.

The 2% royalty works out to US$30 million or G$6.180 billion, assuming the number of production days in the year will be 300, and the price of crude oil will be US$50 per barrel. The difference of US$350 million would represent 50% profits which amounts to US$11.67 per barrel (i.e. US$350 million ÷ 30 million barrels). Therefore, the total cost of production per barrel will be US$26.66 (i.e. US$50 – US$23.34).

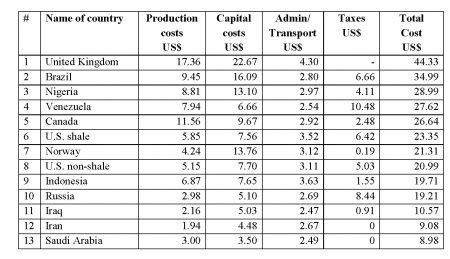

Cost structures, however, vary considerably from country to country, as can be gleaned from Table I published by the Wall Street Journal of 15 April 2016.

Table I

As can be noted, the UK has the highest capital costs of US$22.67 per barrel which work out to 44% of the revenue earned. This is because its operations are offshore in deep, stormy waters and require more advanced and costly technology to extract oil and gas. On the other hand, Saudi Arabian crude is one of the cheapest in the world to extract because of its location near the surface of the desert and the size of the fields. Its capital costs are 6.7% of the revenue earned.

In the case of Guyana, we are informed that 75% of the revenue earned will be applied against the cost of investment which works out to US$37.50 per barrel, 65% higher than that which obtains in the UK. When production costs, administrative and transportation costs, and taxes are taken into account, the total cost per barrel of oil is more than likely to exceed the price of US$50. Will ExxonMobil continue production if it is unable to break even? Or, is it a case where the capital expenditure has been over-estimated? The only hope is that there will be a significant increase in the price of crude oil by the time production begins. However, with the Paris Climate Change Agreement in force, there is a distinct shift towards clean renewable energy from hydropower, wind, solar and other sources, and the related costs have significantly decreased. All the indicators are that in the near future it would be economically more feasible to generate electricity from renewable sources rather than from crude oil. The most recent edition of the “Economist” suggests that the end of the internal combustion engine is in sight, given the rapid gains in battery technology. Several countries, including, Britain, France, Germany and India are phasing petrol-powered vehicles out in favour of electric ones.

In a previous column, we had suggested that in the early years of the project, it is unlikely that a profit will be made, since “dry hole” costs have to be recovered immediately while costs relating to successfully exploration have to be amortised over the life of the project, consistent with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAPs). Our concern remains valid.

In today’s article, we begin a discussion of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), a global Standard to promote open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources.

The EITI in perspective

The EITI was first launched in 2002 at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, South Africa. This was followed by a conference in London in 2003 at which a number of countries, companies and civil society organisations agreed to the following Statement of Principles to increase transparency over payments and revenues in the extractives sector.

- We share a belief that the prudent use of natural resource wealth should be an important engine for sustainable economic growth that contributes to sustainable development and poverty reduction, but if not managed properly, can create negative economic and social impacts.

- We affirm that management of natural resource wealth for the benefit of a country’s citizens is in the domain of sovereign governments to be exercised in the interests of their national development.

- We recognise that the benefits of resource extraction occur as revenue streams over many years and can be highly price dependent.

- We recognise that a public understanding of government revenues and expenditure over time could help public debate and inform choice of appropriate and realistic options for sustainable development.

- We underline the importance of transparency by governments and companies in the extractive industries and the need to enhance public financial management and accountability.

- We recognise that achievement of greater transparency must be set in the context of respect for contracts and laws.

- We recognise the enhanced environment for domestic and foreign direct investment that financial transparency may bring.

- We believe in the principle and practice of accountability by government to all citizens for the stewardship of revenue streams and public expenditure.

- We are committed to encouraging high standards of transparency and accountability in public life, government operations and in business.

- We believe that a broadly consistent and workable approach to the disclosure of payments and revenues is required, which is simple to undertake and to use.

- We believe that payments’ disclosure in a given country should involve all extractive industry companies operating in that country.

- In seeking solutions, we believe that all stakeholders have important and relevant contributions to make – including governments and their agencies, extractive industry companies, service companies, multilateral organisations, financial organisations, investors and non-governmental organisations.

As a consequence of the above, the EITI Association was established under Norwegian law and currently comprises 52-member countries. With an International Secretariat, and a 21-member board drawn from governments, civil society and industry, the EITI seeks to strengthen government and company systems, inform public debate and promote understanding. In each of the implementing countries, the EITI is supported by a coalition of government, companies, and civil society.

It shares the belief that natural resource wealth should benefit citizens and that this requires high standards of transparency and accountability.

The EITI has promulgated standards to which participating countries are required to observe. A key requirement is for countries to publish timely and accurate information on key aspects of their natural resource management, including how licences are allocated, how much tax and social contributions companies are paying and where this money ends up in the government.

Through the EITI, companies, governments, and citizens increasingly know who is operating in the sector and under what terms, how much revenue is being generated, where it ends up and who it benefits. From the perspective of the State, the EITI helps to improve the investment climate by providing a clear signal to investors and international financial institutions that there is commitment to greater transparency. It also assists in improving governance and promoting greater economic and political stability.

EITI application process

Before an application is made for membership of the EITI, the following steps (known as “sign-up” steps) must be first completed:

(a) Government engagement, including the appointment of a senior official to lead the implementation;

(b) industry engagement;

(c) civil society engagement;

(d) establishment and functioning of a Multi-Stakeholder Group (MSG), comprising civil society, industry and Government to oversee implementation; and

(e) an agreed work plan with clear objectives for EITI implementation and a timetable that is aligned with the deadlines established by the EITI Board.

To be continued –