Intangible

Intellectual property (IP) is one of those intangible things that is important to the production structure of any country. As abstract as the concept might seem, it is capable of generating future benefits for its owners. That is the reason accountants normally view intellectual property as an intangible asset; a thing of value to those who own it. The property can be sold or it could be leased to others. When those options are not exercised, the owners could use the knowledge to produce goods or services. Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) therefore are about access to technology and the ability to use the technology in the production process through an arms-length exchange in the market place.

Knowledge

Before discussing the value of intellectual property to the economy, it would be useful to offer an explanation of IPRs. IPRs are about knowledge that comes in different forms. They refer to creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; designs; and symbols, names and images used in commerce. To a large extent, they are things that are available for sale. The rights contained in IPRs are attached to ownership of the product or process that is used in production. Rights are protected in law in order to give effect to markets, enabling individuals to earn both recognition and financial gain from what they invent or create. Intellectual property rights therefore are the rights given to persons over the creations of their minds, usually giving the creator an exclusive control over the use of their creation for a given period of time. As a right, it lets the owners of the property use it how they want. By striking the right balance between the interests of innovators and the wider public interest, the IP system aims to foster an environment in which creativity and innovation can flourish.

The issue of property rights is both a domestic one and an international one. The common thread between the two is the desire to create a market for the exchange of intellectual property rights. Innovation and creative thought would never flourish if there was no way of owners gaining a return on their investment. Markets are the places where returns are had or losses are made. Both the domestic and international markets are concerned with avoiding the free-rider problem, that situation in which the market fails because it was unable to enforce the principles of excludability and rivalry.

Features

As alluded to earlier in this article, property rights have three principal features. The first is that they give the owners the exclusive authority to determine how a resource is used. They can rent it. They can sell it. They can develop it or they can simply enjoy it by themselves. The second feature of property rights is that they confer upon the owners the exclusive right to control the benefits that are gotten from the resources. Where such rights are put in the market place, the income or profits that an owner receives is used in a manner determined solely by him or her. The third feature of property rights is that it confers the right to execute the choice of use of the resources on mutually agreeable terms. That exchange would not be possible without a market and, if an exchange were to occur, the cost would be much higher than one with a market. While the use of intellectual property rights is about what takes place in a domestic economy, access to the technology quite often carries an international focus. The international focus is concerned with getting the international market to work effectively. In this case, discussions about IPRs are about the economic relationship between countries around the world, but especially between developed and developing countries.

In the international arena, IPRs laws fall under the Agreement in Trade Relates Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), which came into effect on January 1, 1995. Obviously, 1995 was a breakthrough year for international trade. It was the year the WTO came into effect. With it came the GATS and the TRIPS, both achieving global recognition and wider participation, particularly by developing countries. TRIPS also brought with it more formal obligations than existed before on the part of participating member states. The rules of the agreement seek to cover copyright and related rights (ie the rights of performers, producers of sound recordings and broadcasting organizations); trademarks including service marks; geographical indications including appellations of origin; industrial designs; patents including the protection of new varieties of plants; the layout-designs of integrated circuits; and undisclosed information including trade secrets and test data.

Novelty

The novelty about TRIPS was that it finally provided a means of comfort to the developed countries. Throughout the negotiating period, developed countries saw the tolerance of piracy by national authorities as a barrier to trade. This was a unique perspective since this problem in international exchange was not a case of little or no market access. It was a case of too much access with few benefits accruing to the owners of products and ideas. It was the burning issue for developed countries which contended that they lost billions of dollars every year as a consequence of the failure of national authorities to stem the tide of piracy. The economic impact was greater than revenue loss. Some estimates indicate that IP-intensive industries accounted for as much as 20 per cent of jobs and nearly one-third of the gross domestic product (GDP) of countries that depended on the production of intellectual property revenues.

TRIPS therefore had opened the door to the creation of a more robust and stable market in intellectual property rights. It did so by creating a comprehensive legal multilateral agreement among members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on intellectual property by which all

members are expected to abide. By creating the rules, it also created a basis on which to enforce the rights of property owners.

Ineffective

It is not that market protection for intellectual property did not exist before. It is just that it was limited and fragmented, and consequently ineffective. The two most prominent conventions that sought to create and protect the intellectual property markets before the emergence of TRIPS were the Paris Convention and the Berne Convention. Each of these conventions sought to protect a part of the market. For example, the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property which was established in 1883 seeks to protect patents, utility models, industrial designs, trademarks, service marks, trade names, indications of source or appellations of origin, and the repression of unfair competition. The Berne Convention which was established in 1886 sought to protect every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain.

The coverage of the Berne Convention did not discriminate with respect to the mode or form of its expression. As a result, things such as books, pamphlets and other writings; lectures, addresses, sermons and other works of the same nature; dramatic or dramatico-musical works; choreographic works and entertainments in dumb show were covered. Appearing as if it was afraid to miss anything, the Convention also included musical compositions with or without words; cinematographic works to which are assimilated works expressed by a process analogous to cinematography; works of drawing, painting, architecture, sculpture, engraving and lithography; photographic works to which are assimilated works expressed by a process analogous to photography; works of applied art; illustrations, maps, plans, sketches and three-dimensional works relative to geography, topography, architecture or science.

A third mechanism which appears in 1961 was the Rome Convention. This Convention, on the face of it, seems to duplicate the purposes of the Berne Convention with its focus on protecting the market for performers, producers of phonograms and broadcasting organizations. Like the previous two conventions, it did not have the ability to protect the market effectively. The three conventions were seen largely as national creations to protect inventions and innovations in domestic markets. They were not designed to promote trade in rights. The effort to achieve that objective emerged with the formation of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).

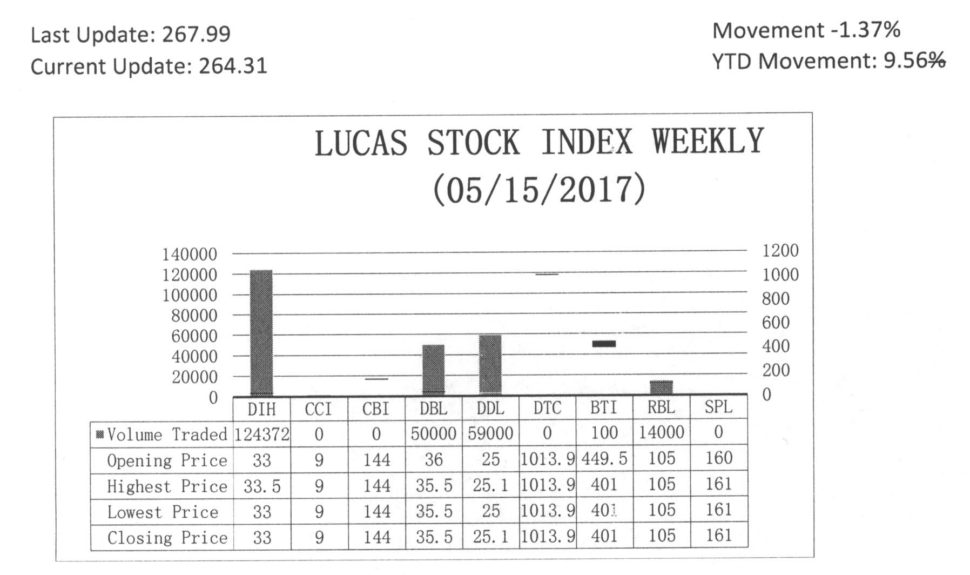

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) fell 1.37 percent during the third period of trading in May 2017. The stocks of five companies were traded with 247,472 shares changing hands. There as one Climber or two Tumblers. The stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) rose of 0.4 percent on the sale of 59,000 shares. The stocks of Demerara Bank Limited (DBL) fell 1.39 percent on the sale of 50,000 shares while that of Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry fell 10.79 percent on the sale of 100 shares. In the meanwhile, the stocks of Banks DIH (DIH) and Republic Bank Limited (RBL) remained unchanged on the sale of 124,372 and 14,000 shares respectively.

To be continued